Image from Getty Images

High inflation and low skilled labor availability continued to hammer health care construction over the last year. Mix in supply chain shortages, which are still limiting the availability of key equipment and building materials, and it’s easy to see why hospital construction managers may be banging their hard hats in frustration.

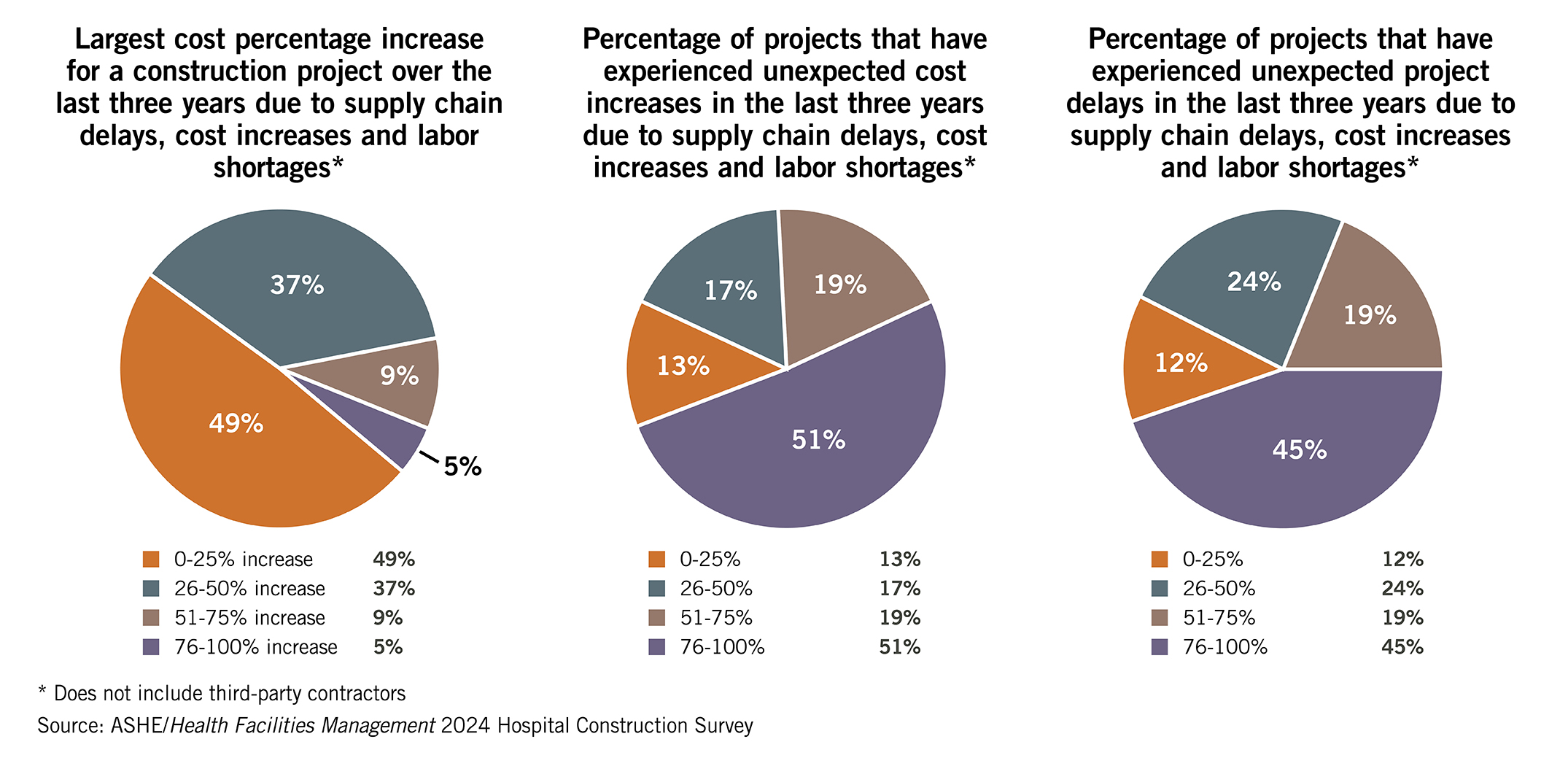

According to the 2024 Hospital Construction Survey, nearly half of health care respondents have seen construction cost increases and delays on 76% to 100% of their recent projects.

“The last three years have just been a rollercoaster ride for health care construction,” says Ken Cates, principal at Northstar Management Company, St. Louis, a project management firm specializing in health care construction. “Every time you turn around there is an increase in cost, and projects take longer due to supply issues.”

Conducted annually by the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s (ASHE’s) Health Facilities Management magazine, the Hospital Construction Survey received responses from more than 500 hospital and health system managers and executives who oversee construction projects as well as third-party architecture, engineering and construction professionals, to weigh in on issues impacting the field.

Click the chart above and use the arrows to view data from the ASHE/HFM 2024 Hospital Construction Survey

While health care organizations emerged from the pandemic eager to resume projects, inflation, supply chain issues and labor shortages continue to interfere with budgets, timelines and even project approval, according to Chad Beebe, AIA, CHFM, CFPS, CBO, FASHE, deputy executive director of regulatory affairs at ASHE.

“A lesson learned for the industry over the last couple years is that health care isn’t immune to these market issues,” Beebe says. “It is having an impact everywhere, and it’s something to be concerned about.”

The issues are equally frustrating for hospital staff and construction firms, and have made planning for any project taking place in the next one to three years extremely difficult, says Adam Ashouri, senior project manager at Meyer Najem Construction, Fishers, Ind.

“It is like looking into a crystal ball — everyone is taking their best educated guess,” Ashouri says. “We’ve had to get pretty creative with the strategies we employ to insulate our clients and ourselves from these price and schedule duration increases. Market forces need to be understood and considered during project planning and programming.”

One strategy: Ashouri asks contractors submitting bids on projects to guarantee costs for 60 days. This is because, right now, prices can wildly fluctuate even within 60 days. “It gives our clients more runway to make decisions, get regulatory approvals, secure funding or react to unfavorable bid results,” he says.

Supply of equipment and construction materials has not come online as fast as the demand for those products following the COVID-19 pandemic, Ashouri says, especially since a backlog of construction projects was released into the market once COVID-19 restrictions began to ease in 2021 and 2022. This occurred at the same time that manufacturing to create materials for those projects faced increasing labor and supply chain issues.

Labor, prices and materials

Though health care construction overall continues to accelerate post-pandemic, issues like inflation, labor shortages and supply chain interruptions have put a damper on the trend. The survey asked respondents to note plans for 20 construction project types within the next three years. Of those projects, more than half decreased compared to the previous survey — acute care planning decreased by 12%, specialty hospitals by 7% and central energy plant construction by 6%. Given the climate, health care executives are increasingly deciding to hold off on new projects to see if market conditions settle down and they can get better pricing or lead times on materials, Cates says.

“I can’t tell you how many executive meetings I’ve been in where that’s the topic, with people saying ‘Well, what if we push it off a year, maybe pricing will be better,’” Cates says. “Limited cash flow for projects and potentially even an oversaturation of new facilities that rose in the last 10 to 15 years could also be a factor [in the lower number of reported projects].”

While inflation and material delay issues persist, skilled labor has become hospital construction’s biggest current challenge, Cates says. “It’s basic economics,” he explains. “There are limited resources with less people stepping in to fill skilled labor roles and more projects competing for the labor resources that remain.”

Ashouri notes demand for health care construction has not decreased, just the ability to execute it within previously allotted budgets — in part due to competition for labor. “If we’re building a $15 million medical office building in Indianapolis, we’re going to be competing for the same labor pool as somebody who’s building a $1.5 billion manufacturing campus up the road,” he says.

To keep these issues in check, the health care construction field has made adjustments in the size of construction projects and materials used, according to the survey. Reducing the scope of their project (65%) and using value engineering (56%) are ways most survey respondents say they have dealt with current construction challenges.

“The biggest challenge with this environment is getting projects done that need to get done,” says Gordon Howie, MSPM, CHFM, CHC, SASHE, regional chair for facilities and support services at Mayo Clinic Health System – Eau Claire in Wisconsin and ASHE Advisory Board past president. “The cost per square foot has gone up significantly, but the capital outlay that we get hasn’t gone up in relationship to those costs. It forces organizations to do a good job of prioritizing projects and being more strategic where they put their dollars. Some are using the strategy of phasing projects to give some flexibility with schedules and cash outlay.”

With these issues now stretching into years, health care organizations can’t just accept that their projects will be over budget and behind schedule, says Michael Hatton, MBA, CHFM, FASHE, vice president of system facilities engineering/construction at Memorial Hermann Health System, based in southeast Texas, and ASHE Advisory Board president-elect.

Times like these call for better planning and “bringing your key team members on early to lock in resources before they go down the street to another job,” Hatton says. “If you analyzed lead times and did a good job of budgeting from the outset, you shouldn’t see those issues.”

In Texas, challenges like inflation and labor issues are evident but haven’t stopped health care construction, which, despite costs going up “30 to 40%” in the last three to four years, “is booming,” Hatton says. But the issues have certainly changed the way projects need to be developed.

“The traditional method of delivering a project has to be reimagined. Pre-COVID-19, you could just dust off construction plans from years before and you’d be safe, but a lot of that has changed,” Hatton says. “You need to get the scope right from Day 1, adjust your schedule for long lead times on key systems, like electrical systems, potentially change your specifications and rethink the planning, design and construction (PDC) process by front-loading the procurement of these key components to stay on track.”

Impacted equipment

Cost and availability woes are not just impacting new construction and renovation projects but also plans to add or replace vital building services equipment. According to the survey, boilers dropped from 11% having been replaced in the last two years in 2023 to just 6% in 2024, and chillers from 13% to 9%.

About this survey

Health Facilities Management surveyed a random sample of 8,801 hospital and health system executives and third-party architecture, engineering and construction professionals to learn about hospital construction trends. The response rate was 6%.

Another factor may be that hospitals decided to act while the money was flowing during the initial months of the pandemic and have already recently replaced key equipment, Beebe says. Additionally, hospitals may be deferring money from infrastructure and mechanical systems projects to help free up capital for strategic construction projects that bring in revenue or have a high community need, Howie says.

Hospitals might also simply be waiting until conditions like timelines improve to purchase things like air handlers, chillers, electrical components or elevators — the latter two of which can take nearly two years to get after an order. “Right now, with big capital assets, you often are simply buying a spot in line as opposed to buying a product,” Ashouri says.

When hospitals decided to open their wallets, it was for equipment that has a highly visible role in patient care, the survey found. The pandemic-driven focus on airflow and infection control continues to impact the health care construction industry. Heating, ventilating and air conditioning topped the survey in the category of new building services equipment investments, with 24% reporting they are currently adding new air handlers, up from 20% last year.

“During the pandemic, air movement became a top issue, not just with facility managers but with even physicians and nurses asking which way the air is flowing,” Cates says. “It brought that infrastructure to the very front and center of health care.”

The top five building services equipment projects being replaced and upgraded by hospitals in the next year are air handlers (24%), elevators (15%), chillers (14%), electrical switchgear/transformers (14%) and plumbing (12%). One reason for an uptick in many of these replacements, Hatton says, is the fact that health care as a field has not gotten ahead of the deferred capital replacement curve. “Many in health care have grossly underemphasized the need for systems replacements, so deferred and then during COVID-19 got further behind with those systems that needed replacements,” he says.

Electrical systems have been in the top five projects for the last two years of the survey. This trend may be related to ramped up energy management and decarbonization efforts around the country, Beebe says, as more federal, state and local regulations and incentives are put in place to lower health care resource use and emissions. In addition, Hatton notes that the current construction boom with data centers and chip manufacturing centers and the focus on technology is thought to be further causing competition for electrical distribution systems and generators — all of which have lead times well over a year.

Ambulatory on the rise

Despite these challenges, the survey illuminated some bright spots. More organizations are building ambulatory facilities — an increase from 7% in the 2023 survey to 12% in 2024 for “currently under construction.” Construction planned within the next three years remained relatively flat and also sits at 12%.

Hospitals may be building ambulatory facilities to help “pandemic-proof” themselves, Beebe says. After being forced to temporarily shut down key revenue-producing inpatient services, hospitals may be looking to diversify their portfolios. Also, several high-reimbursement procedures like knee and hip replacements have moved from inpatient to outpatient procedures.

Finally, the push toward ambulatory services by hospital systems may be a competitive reaction to the rise of hospital-affiliated urgent care centers and even new companies like Amazon and CVS entering the health care marketplace and pulling away patients with convenient and accessible care options.

Ambulatory facilities are generally less expensive to construct and build to code, something attractive in this environment, Ashouri says, and can give hospital systems a new line of revenue and a testing ground for a new market. “We joke that when you see a new ambulatory surgery center, there is a better-than-average chance that a new patient tower will be built behind it in the next five to 10 years,” he adds.

Technology investments

Better connected hospital equipment and systems were also identified as priorities in the survey. Ranked in the top five projects last year, data/network infrastructure projects were No. 6 this year for “currently replacing” as facilities work to leverage data to identify operational improvements. Upgrades to hospital building controls/automation ranked No. 1, with 20% reporting replacement in the next 12 months.

Unfortunately, new technology also opens the door to more cybersecurity issues. As more critical systems like HVAC, electrical and even elevators become connected to facilities’ information technology (IT) networks, the risk of those systems having vulnerabilities that can be compromised during a cyberattack increases. “A key issue: many facilities managers and even IT staff don’t know everything in their hospital that has an internet connection,” Beebe says.

While facilities and IT managers may argue whether building systems should be on their own isolated network or connected to a hospital’s main system — which is usually connected to the internet — the conversation should instead be centered on working together to offer the greatest level of protection overall, Howie says. Proper vetting and testing of equipment purchases, especially from overseas vendors, is also necessary to ensure they don’t compromise a network.

Silver linings

Despite, and likely due to, the ongoing issues with cost, labor and materials, hospital construction managers are learning how to better wrangle projects in the current environment. The 2024 survey showed slightly more construction projects (43%) are on schedule and on budget, up from 40% last year. Also, fewer projects were reported over budget and behind schedule (23%).

This sunnier outlook on timelines and budgets is not likely due to actual field improvements in costs and supply chain issues but to a change in expectations and more front-loaded, accurate planning on projects, Beebe says.

“We’ve realized it is going to take longer, so have increased our timelines, and it is going to cost more, so have adjusted our projects and budgets,” Beebe says. “We now aren’t getting caught by surprise with these challenges like in previous years. We are taking on smaller, more calculated, strategic projects, doing only what we have to do and can afford to do within an adjusted timeline.”

A silver lining of these challenges is better planning on the front end. Health care organizations are being more selective as to which projects get greenlighted, taking a hard look at need and sometimes even scrapping projects mid-design if they find they can’t afford to build.

“We used to throw architecture or space at a problem: if there are too many people in a waiting room, expand the waiting room, or if we are running out of parking, well, just expand the parking lot,” Beebe says. “But now that costs are up, we are taking a closer look at the problem and not relying on additions or construction to fix it. The questions become, ‘Why are there so many people in the waiting room?’ ‘On the parking lot, is this a throughput issue?’ ‘Can we solve these problems without changing the physical environment?’”

Health care organizations are also getting smarter about how they plan construction projects and who is invited to the table from the start. “At all levels of PDC, we’ve been forced to improve our skill sets related to communication and strategic thinking,” Cates says.

Hospital PDC professionals are proactively assembling wider-reaching project teams earlier, bringing together facilities managers, suppliers, construction firms and even major subcontractors early in the planning and design process to determine how to get the best value, clearest budget and most manageable timeline for a construction project — instead of just relying on architects to estimate the costs and schedule for a project.

“When you have that information in the room for the decision-makers to hear, they’re able to make better decisions sooner,” Cates says. “Savviness over the last three years has just gone through the roof, and that is a really good thing for our industry. Painful at times, but ultimately good.”

Chris Dimick is content development and communications manager for the American Society for Health Care Engineering and production editor for Health Facilities Management (HFM) magazine, and Jamie Morgan is senior editor for HFM.