|

|

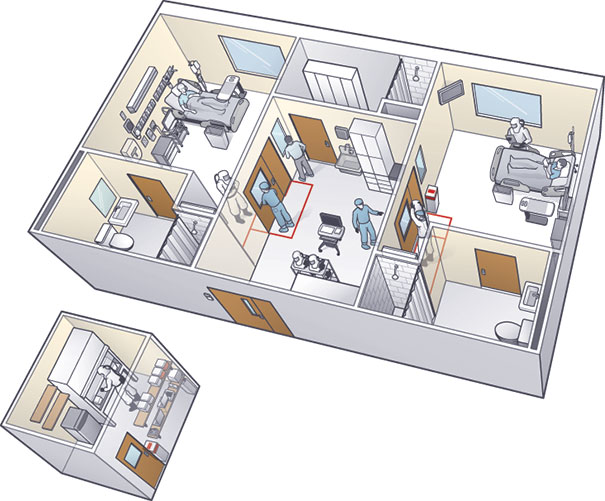

ILLUSTRATION BY DAMIEN SCOGIN The isolation unit in which Emory University Hospital treated patients with Ebola features an anteroom that separates two patient rooms and a new lab (left of unit) that was built a few feet outside the space to keep staff safe. |

Two U.S. health care facilities that successfully treated patients with Ebola recently shared some key strategies for limiting exposure risk to patients and hospital staff and for other related challenges.

Late in 2014, Emory University Hospital in Atlanta treated four patients with Ebola in a previously lightly used isolation unit it had opened 12 years earlier. The serious communicable disease unit (SCDU) at Emory was established in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), says Charles E. Hill, M.D., director of the Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory and program director of pathology residency programs at the hospital. The unit, which was designed to care for persons with airborne diseases, contains three patient rooms. Air in the rooms is under negative pressure, with all airflow going from the hallway to the anterooms to the patient rooms. Also, air in the rooms has a laminar flow across the patient bed to reduce contamination risks.

Air from patient rooms undergoes high-efficiency particulate air filtration before it is fully exhausted to the outside. The outside exhaust is separate from other hospital air intakes and is high enough to allow any particles to disperse.

Access to the SCDU is restricted to a small, specially trained team of clinicians, primarily infectious disease physicians and critical care nurses.

Hill says one aspect of the SCDU that changed from the original design was the location of the lab equipment, which was placed inside a biosafety cabinet in the anteroom. The staff decided that “in an abundance of caution, no diagnostic specimens of any kind would leave the unit for testing, with the exception of any that might be collected by and delivered to the CDC or other appropriate government health agencies,” states a report written by Emory clinicians for Laboratory Medicine, published by the American Society for Clinical Pathology.

To maintain staff safety when a second patient was admitted to the unit, a second lab with identical equipment as the original was created in a space about 10 steps outside the anteroom. Hill credits facility manager Jerry Lewis and his staff with creating the additional lab, which required installation of new ductwork to supply cool air to keep lab instruments properly calibrated, in less than 24 hours.

Protocols for wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE), including a powered air-purifier respirator, remained in place for anyone entering the new lab, Hill says. Additional steps were taken to increase already rigorous safe transport of patient specimens from the anteroom to the new lab by putting double-bagged and cleaned specimen bags into a hazardous material box moved by a transporter wearing droplet precaution equipment, he says.

The SCDU and all the meticulous steps that exceeded CDC requirements paid off. All four patients were discharged virus-free and no staff became sick, Hill says.

Meanwhile, the Nebraska Biocontainment Patient Care Unit at the Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, developed a strategy to simplify the otherwise complicated process of waste disposal, according to a report published in the American Journal of Infection Control.

According to a case study in the journal, treating patients with Ebola produced about 23 cubic feet — more than 50 pounds — of solid waste per day, most of which was PPE worn by staff. Additionally, the patients produced approximately 2.3 gallons of liquid waste per day.

According to the Department of Transportation, which regulates hazardous material, Ebola waste is considered Category A, which means the waste is known or expected to contain a pathogen capable of causing fatal disease. Waste in this category requires several steps, including a special permit, to ensure safe disposal.

The Nebraska biocontainment unit developed a strategy to convert Category A waste into Category B medical waste to enable safe disposal. The unit transferred all solid waste, including PPE, patient linens, scrubs, towels and more to a pass-through autoclave system for sterilization. Autoclaved waste was placed in biohazard bags and into rigid packaging for disposal as Category B medical waste.

Liquid waste produced by patients with Ebola was disposed of into a toilet with hospital-grade disinfectant and held for 2.5 times the recommended time before flushing. The method surpasses the CDC guidance regarding Ebola liquid waste removal.