Midland (Texas) Memorial Hospital went from an EPA Energy Star score of 12 to 75 after implementing a systematic approach to reducing energy consumption.

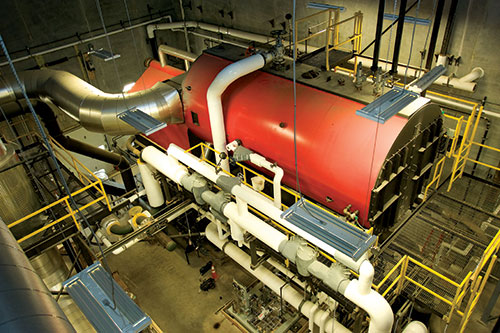

When Antonio Suárez, CHFM, SASHE, joined Midland (Texas) Memorial Hospital as director of facilities services in 2010, he found an employer that already prided itself on energy conservation. The hospital was finishing a lighting retrofit that replaced T12 fluorescent tubes with T8s. A new patient tower under construction had been designed to the 2003 International Energy Conservation Code, and the central plant had been modernized and expanded for efficiency and additional capacity.

“Midland Memorial thought it was cutting-edge then when it came to energy efficiency," Suárez recalls. "What I brought to the table was the question, 'How do we know this?' We weren’t measuring."

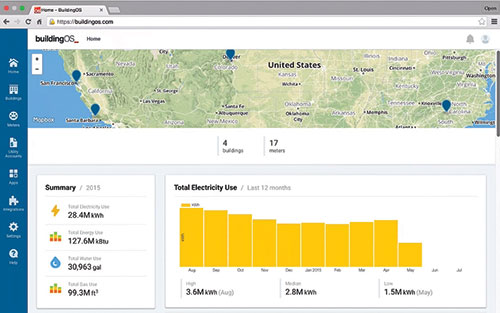

So, the hospital began benchmarking its energy performance using the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA’s) Energy Star Portfolio Manager, a free tool that allows facilities to track their energy usage and compare their energy use intensity (EUI) measurements to national averages (based on an algorithm that normalizes for climate differences, operational intensity and size).

"We learned that we were really sucking wind," Suárez says. "We had a score of 12, which means we were in the 12th percentile nationally, while the average hospital in the United States has a score of 50." Energy Star recognizes health facilities that are in the top quartile.

After this wake-up call, Midland Memorial implemented a systematic approach to reducing energy consumption. Today, the hospital has an independently verified score of 75 and recently submitted an application to the EPA for Energy Star certification.

"To paraphrase Nick Saban, head coach of the University of Alabama football team, you need to have a vision, you need to have a process, and you need to have the discipline to follow the process," Suárez says, explaining the hospital's success at energy reduction. "That's what gives you outcomes."

Waste not, want not

Reducing energy use requires planning, persistence, ongoing benchmarking and staff buy-in — from the C-suite to maintenance and housekeeping personnel — emphasizes Terry Scott, CHFM, CHSP, SASHE, president of the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE). It's not difficult to do, but it requires commitment and effort, he says.

You may also like |

| The business case for energy management |

| Benchmarking energy performance |

| On-site power generation alternatives |

|

|

With health care costs escalating and the reimbursement formula for hospitals changing, every health system must prioritize saving money, including those that champion environmental sustainability. Luckily, reducing energy consumption is a win-win, decreasing both energy costs and a hospital's carbon footprint at the same time, Scott points out.

On a per building basis, hospitals use an average of 600,000 million British Thermal Units of energy per year, significantly more than any other building type, states the Department of Energy's (DOE’s) Advanced Energy Retrofit Guide for Healthcare Facilities, published in September 2013. Stringent codes are in place to prevent the spread of infection and protect patients. But even so, many opportunities exist for substantially reducing energy waste, says Scott, a system director of engineering services for Houston-based Memorial Hermann Health System.

As much as 30 percent of the energy consumed in hospitals and other types of commercial buildings is used unnecessarily, according to the EPA's Clark A. Reed, the national program manager for Energy Star Commercial Buildings. Given that energy is approximately 50 percent of a health care facility manager's budget, hospitals can slash their operating costs by using energy more efficiently, Scott insists.

Indeed, Memorial Hermann has saved $87 million since beginning its energy conservation initiative in 2008, using a cost-conscious approach of pursuing primarily easy-to-remedy inefficiencies.

When the health system first benchmarked using Portfolio Manager, most of its hospitals scored only in the single digits on the Energy Star scale, acknowledges Michael Hatton, RPA, SMA, CHFM, SASHE, Memorial Hermann's vice president of facilities engineering. "We were the worst of the worst at the time," he says.

Today, nine of its 14 hospitals are Energy Star-certified, which puts Memorial Hermann in rare company. Only 56 hospitals across the country earned this certification in 2015, according to Reed.

Low-hanging fruit

After benchmarking each facility's overall energy performance, health systems should undertake an energy audit to systematically assess energy usage, recommends the DOE’s health facility retrofit guide. Generally conducted by outside consultants or service providers, energy audits range in detail from simple walkthroughs to detect inefficiencies to comprehensive analyses that involve placing submeters on individual building systems.

Eight years ago, La Crosse, Wis.-based Gundersen Health System was surprised by the findings of its energy audit. "We found a huge opportunity for improvement. We were shocked," says Jeff Rich, executive director of Envision, Gundersen's sustainability program, which is known for its innovative use of renewable energy [see sidebar, Page 23]. "So, we started by focusing on energy efficiency because that's where the financial returns are best. In the first six months, we made some real quick improvements and got some momentum, and the program grew from there." Most health systems can save 20 to 30 percent in energy costs through such measures, Rich says.

"Our approach has been to do the simple things first — anything with a payback of 12 months or less — before getting to the point of looking at really efficient chillers and the like," shares Larry Newlands, Memorial Hermann's director of energy management. "There is a huge amount of low-hanging fruit."

Reed says that to realize rapid gains in energy efficiency, the first step is to retrocommission, or fine-tune, existing HVAC equipment and controls, which often fall out of calibration over time. Health facilities commonly can reduce energy expenditures by 10 percent simply through retrocommissioning, he notes.

ASHE's Sustainability Roadmap recommends preventive maintenance to optimize HVAC efficiency. For example, air handling unit filters should be replaced regularly and cooling towers cleaned to maximize condenser performance. The DOE estimates that as much as 20 percent of the steam generated by a typical boiler is lost due to leaking or failing steam traps, which should be repaired or replaced.

Memorial Hermann initially achieved a large proportion of its savings by turning off or turning down heating and cooling when and where it wasn&8217;t needed. In many cases, this cost nothing because it simply required reprogramming different set points and schedules in the base building control system, Hatton explains. "Administrative areas, for example, don't need to be perfectly climate-controlled 24 hours a day, seven days a week," he says.

Midland Memorial has minimized energy-related capital investment by integrating energy conservation into other infrastructure projects. For example, when the hospital's chiller system needed a major reconfiguration due to insufficient water flow, variable-speed drives were installed and three-way valves were replaced with two-way valves.

"We changed it from a constant-volume to a variable-volume system," Suárez says. "This yielded savings. But the project was originally undertaken out of necessity." Similarly, Midland Memorial "tagged on" energy-efficiency measures when it replaced old air-handling units in its operating rooms.

For the most part, energy-conserving hospitals replace HVAC equipment and systems with more efficient options at the end of their useful lives. "More often, we wait until equipment is completely depreciated," says Steven Cutter, HFDP, CHFM, FASHE, director of engineering services at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H. "But if we find a piece of equipment that’s a real energy hog, then we would certainly consider replacing it ahead of time."

Smart investments

After realizing significant savings from quick fixes, health systems need to consider projects with somewhat longer returns on investment. Operating room (OR) airflow setbacks, for one, can produce tremendous payback, especially for larger health systems.

Four-time Energy Star Partner of the Year Cleveland Clinic is in the midst of one of the largest health care lighting retrofits in the country.

Cleveland Clinic, which operates nine community hospitals in Ohio besides its flagship campus, expects to save $2 million a year in energy costs from the OR setback program it will finish rolling out this year, says Jon Utech, senior director of the health system’s Office for a Healthy Environment. When the ORs are not in use, the number of air changes per hour drops from 20, the minimum required during surgeries, to six — while the temperature, humidity and pressure of the room remain the same.

The setbacks are tied to the OR management component of Cleveland Clinic’s electronic health record system. If a surgery runs longer than the schedule indicates, a built-in safety feature prevents the setback from occurring if the operating table light remains on.

A four-time Energy Star Partner of the Year, Cleveland Clinic is also in the midst of one of the largest health care lighting retrofits in the country, replacing fluorescent tubes with light-emitting diode (LED) technology. "We're going to have a quarter million LED tubes in place by the end of the year," Utech says.

"Once you retrofit the fixtures, the payback is less than four years just on energy savings," he notes. "And when you take maintenance costs into account, it's about two years."

In May, Cleveland Clinic announced the establishment of a $7.5 million Green Revolving Fund to finance future energy-efficiency projects.

New construction opportunity

Of course, new construction offers the biggest opportunity for incorporating energy conservation best practices. As part of a $2 billion capital expansion, Memorial Hermann not only is incorporating LED lighting throughout, but also air-conditioning heat recovery, variable-speed pumping systems and improved thermal insulation on walls and roofing systems.

"The system is building two new hospitals," Scott says. "Within one year, they are required to be Energy Star-certified, with a score of 75 or higher. This is not a common practice in the industry."

Innate shading opportunities from a building’s geometry and orientation can help with energy efficiency in facilities like the Memorial Hermann Convenient Care Center in Cypress.

Gunsolus recommends that energy modeling be done very early in the process to inform building design. "First, we look at basic orientation," he says. "Typically, you try to avoid large expanses of eastern and western exposures; that's a general rule of thumb in the United States. If that is not an option, there are architectural and landscape strategies that can help to mitigate energy inefficiencies."

Also, certain building shapes are conducive to energy conservation. "A compact footprint is typically an efficient footprint, especially when oriented properly," Gunsolus says. "Sometimes, though, you may want to use an H-shape or a C-shape — something with a courtyard that allows you to take advantage of daylight harvesting opportunities. You can also benefit from innate shading opportunities provided by the building itself just from its geometry. " Motivated staff

Finally, architectural and engineering solutions must be reinforced by motivated hospital staff. At Cleveland Clinic, all employees and contract workers are required take an online class on reducing energy consumption. "We have trained 57,000 people on energy conservation in the past 18 months," Utech says.

A participant in the United Nations Global Compact, which emphasizes sustainability, the health system further communicates its energy-reduction message via electronic message boards, newsletters and many other touch points.

To engage clinical staff, Cleveland Clinic established a Greening OR Committee. "When you have physicians leading the charge, it makes a big difference," Utech observes.

Memorial Hermann, which benchmarks monthly, encourages friendly competition among facility managers at its hospitals to stoke enthusiasm for energy conservation. High-performing teams are rewarded with praise, barbecues and publicity.

At Midland Memorial, plant engineers must take ASHE’s online Energy University classes, once per month. "You listen to a short webinar and take a quiz to show that you have competence," says Suárez, who serves on ASHE's board of directors.

On behalf of the Texas Association of Healthcare Facilities Management, Memorial Hermann for several years has organized the Texas Renewable Energy Roundup, a statewide energy-reduction competition for hospitals. For two of the past three years, including this year, Midland Memorial came in first place in the large hospital category.

"I called Terry Scott and said, 'You live in my shadows,'" jokes Suárez. "That's how we celebrate."

The Ohio Society for Healthcare Facilities Management joined the competition in 2015, bringing the total number of participating hospitals to 141. As ASHE's president, Scott has been traveling to other state chapters to fire up interest in the challenge.

"We're trying to expand to eight different states and we accept all newcomers," he says. "The main thing we're stressing to facility directors is money savings. It's very big money that they can save their hospitals and put back into health care."