The specialized and especially demanding needs of health care facilities make them a prime environment for commissioning to net the greatest value. However, with no unilateral health care-specific standard, facility managers often were left to cobble together a number of commissioning guides to arrive at a less-than-ideal commissioning process and lingering doubt regarding the adequacy of commissioning in a number of areas.

The specialized and especially demanding needs of health care facilities make them a prime environment for commissioning to net the greatest value. However, with no unilateral health care-specific standard, facility managers often were left to cobble together a number of commissioning guides to arrive at a less-than-ideal commissioning process and lingering doubt regarding the adequacy of commissioning in a number of areas.

That is why the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) in 2010 developed and published the Health Facility Commissioning (HFCx) Guidelines to fill this void in standards for commissioning work specific to health care facilities. ASHE envisioned the need to go beyond the industry-standard commissioning scope and develop a process that is health care-focused and maximizes the deliverables and tools for the health facility manager.

The HFCx Guidelines became the first set of comprehensive standards for implementing a commissioning program specifically addressing health care facilities and their unique needs. For two years, the HFCx Guidelines set a new standard for health care commissioning, finally giving health facility managers the tool they need to understand and promote the value of commissioning to organizational leadership.

The document establishes strategic goals and objectives for the commissioning process, with overview of tactical level processes, tasks, activities, deliverables and details of the commissioning process. Because it was developed with the hope of becoming enforceable standards, it is not especially prescriptive.

Earlier this year, ASHE published a follow-up publication to the HFCx Guidelines, the Health Facility Commissioning Handbook: Optimizing Building System Performance in New and Existing Health Care Facilities, which goes beyond concepts to provide actual program examples and how-to prescriptive instructions for health facility managers on achieving the standards.

To further empower facility managers to convince top management of the value of commissioning, the HFCx Handbook includes such tools as cost documentation and quantitative data on potential energy savings, cost-reduction and system performance. The HFCx Handbook is an educational companion document to the HFCx Guidelines, with the intent to guide the health facility manager through a successful commissioning process.

Abstract to concrete

While the HFCx Guidelines introduced concepts that are not associated with the traditional design and construction process, the HFCx Handbook takes these concepts and illustrates how they become definitive steps that provide a measuring stick for the project. The book's two dozen appendices include helpful sample documents, including a health care commissioning business plan, a request for quotation and a functional performance testing plan, among others.

Most facility managers are fluent in the functional testing elements of the commissioning process. It's the steps before testing and after occupancy that seem to present the greatest challenges.

It is critical to define the owner's expectations in the programming phase. The owner's project requirements (OPRs) define the functional requirements of a facility and the expectations of the owner as they relate to the systems to be commissioned. The OPRs define "what we want to do." If a facility manager has performance expectations for his or her building, he or she must plan for them, and the OPRs are the vehicles for that plan.

Key to developing OPRs is collaboration of all participants. It is critically important to include plant operations and maintenance (O&M), information technology, security, environmental services and other staff who will have a stake in operating and maintaining the facility.

Based on the OPRs, the basis of design (BOD) provides documentation of the primary thought processes and assumptions driving design decisions intended to meet the OPRs. Some of the key elements of the BOD are applicable codes and standards, outdoor design conditions (such as geography and weather), indoor design conditions (such as temperature, relative humidity and number of indoor air changes) and expected building occupancy for all building uses.

Together, the OPRs and the BOD establish clear goals to determine if the final product has accomplished the project objectives. They are dynamic documents that are updated continually throughout a project to conform to changes in the owner's expectations for success.

Before schematic design begins, the health care commissioning authority reviews the OPRs to verify that they clearly communicate the owner's requirements to the design team. The HFCx Handbook spells out in detail the purpose of the OPRs and BOD, what they should include, how they should be written and who should be involved in the process.

Many consider the ribbon-cutting event to signify the end of the construction process. Through the lens of commissioning, however, this event more accurately cues the beginning of the process because commissioning shifts into high gear once a building is occupied and subjected to the loads of health care delivery conditions.

The HFCx Handbook's chapter on "transition to operational sustainability" defines it as the period that spans the time between construction completion and occupancy, during which great attention is required to preserve operational efficiencies. In this section, the HFCx Handbook provides instruction to effectively prepare the O&M department to achieve planned performance. Among the key areas here are using dashboards to track energy use and trends, training maintenance staff, developing a maintenance budget and completing the statement of conditions.

Additionally, a full chapter in the HFCx Handbook is devoted to the postoccupancy and warranty phase, when a building has been fully operational and may have presented some challenges to facility managers and their staffs. This chapter provides advice on using trend data to anticipate issues before they become problems, to solve problems when they arise and to make adjustments to maintain optimal performance.

The bigger picture

ASHE is throwing its weight behind health care commissioning as the path to optimal facility performance and, ultimately, health care delivery. To accomplish the necessary paradigm shift to move the industry to a critical mass of acceptance, ASHE's process includes these steps:

- Define a commissioning process specifically for the health care industry through the HFCx Guidelines;

- Explain to health care facility managers what they should expect from the commissioning process;

- Develop tools for facility managers that enable them to gain support for the process from the C-suite;

- Explain to the existing commissioning industry what ASHE's process requires and what is expected;

- Produce a how-to handbook for the delivery of the process that is a "deep drill" of the HFCx Guidelines and includes specific examples of the work product that documents the commissioning process, which is the HFCx Handbook;

- Create educational programs for ASHE members at the chapter and national levels that explain how the ASHE commissioning process is different and developed specifically for health care facility managers;

- Develop a certification process for health care facility commissioning providers to aid the industry in identifying providers who understand the process and are certified by ASHE in the same way it certifies health care constructors and facility managers.

ASHE realizes that the complexity of the systems in health care facilities creates an optimization challenge for facility managers. The vast majority of existing facilities have never been commissioned, and most have many opportunities to improve performance.

For this reason, ASHE's commissioning process applies an equal focus on existing facility commissioning and new construction. In fact, ASHE sees this area of commissioning as an opportunity for facility managers to realize savings from system optimization even if the facility isn't planning new construction projects.

The HFCx Handbook contains many examples of how to optimize performance and, most importantly, how to establish a benchmark by which commissioning can be measured for effectiveness, which will lend further credence to the value of commissioning.

|

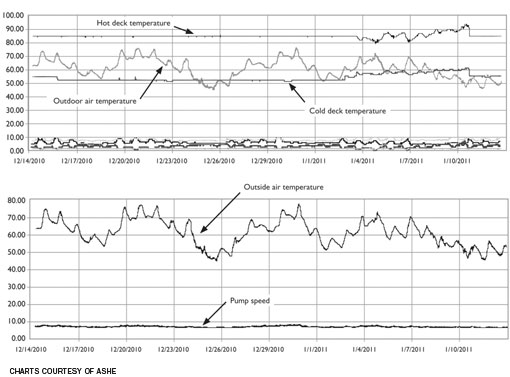

| Excerpted from the HFCx Handbook, these sample trend charts for a double-duct, air-handling unit and a chilled water pump provide examples of the publication’s technical detail. |

A living document

The HFCx Handbook is intended to be a living document that will be revised and improved on a regular schedule, similar to the evolution of the building codes. ASHE has involved professionals from all areas of health care design, construction and maintenance, because commissioning is a function that works best when it reflects the knowledge of all involved in the life of a building.

ASHE will continue to rely on the profession to help shape a process that best serves the health care industry and ultimately provides health facility managers with a complete set of tools needed to achieve a building that operates as it was designed.

Steven R. "Rusty" Ross, P.E., LEED AP BD+C, CxA, is vice president and director of commissioning services for SSRCx, a division of Smith Seckman Reid, Nashville, Tenn., and one of the authors of ASHE's Health Facility Commissioning Handbook. He can be reached at rross@ssr-inc.com.

| Sidebar - The ASHE commissioning process and the 2014 FGI Guidelines |

| The Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities first introduced language regarding commissioning in the 1996/1997 edition, with minimal changes in the 2001 and 2006 versions. Significant changes were made to the text on commissioning in the 2010 edition, with requirements for the basis of design and prefunctional checklist documents and functional performance testing of "systems, rather than just components." These changes recognized the need to document how fundamental design concepts would meet project objectives as well as the growing challenge to validate proper operation of coordinated and integrated systems. As the commissioning process became further embedded in the health care design and construction process, and the value-added proposition has become more validated, the Health Guidelines Revision Committee (HGRC) for the 2014 edition of the FGI Guidelines investigated whether further development of the commissioning requirements would help organizations achieve successful project outcomes. The HGRC appointed a multidisciplinary task force in 2011 to evaluate the current FGI requirements against commissioning standards in the market, including the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) Health Facility Commissioning (HFCx) Guidelines, which were published the previous year. The task force found a number of standards set forth in the HFCx Guidelines that it felt would be beneficial to include in the FGI Guidelines, and submitted proposals to change the language during the open proposal period in fall 2011. The proposed changes were reviewed by the HGRC and accepted to be included in the draft 2014 manuscript presented for public comment from June to November 2012. The basics of the proposal include the following:

Doug Erickson, chair of the 2014 HGRC, notes that the intent behind these proposed changes is improvement in project outcome to help health care organizations meet the escalating challenges in today's health care market. By Clay Seckman, executive vice president and principal for Smith Seckman Reid, Nashville, Tenn., one of the authors of ASHE's Health Facility Commissioning Handbook, and a member of the 2014 Health Guidelines Revision Committee. He can be reached at cseckman@ssr-inc.com. |