There are many overlooked spaces both inside and outside of health care facilities that can be classified as confined spaces.

Image by Getty Images

Health care facilities management professionals are primarily concerned with meeting the vast requirements of The Joint Commission, DNV, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and state and local authorities having jurisdiction, yet they may often miss the fundamentals of a great safety program, which all of these agencies require.

One of these fundamentals is a confined space program as required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). There are two related but different standards regulating confined spaces for routine work atmospheres (OSHA General Industry Standard 1910.146, Permit-required confined spaces) and construction sites (OSHA Construction Industry Standard 1926.21(b)(6)), also addressed in the 2016 edition of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 350, Guide for Safe Confined Space Entry and Work.

OSHA defines a confined space as one that is large enough for an employee to enter and perform assigned work; and has limited means of entry or exit (e.g., tanks, vessels, storage bins, hoppers, vaults and pits); and is not designed for continuous employee occupancy.

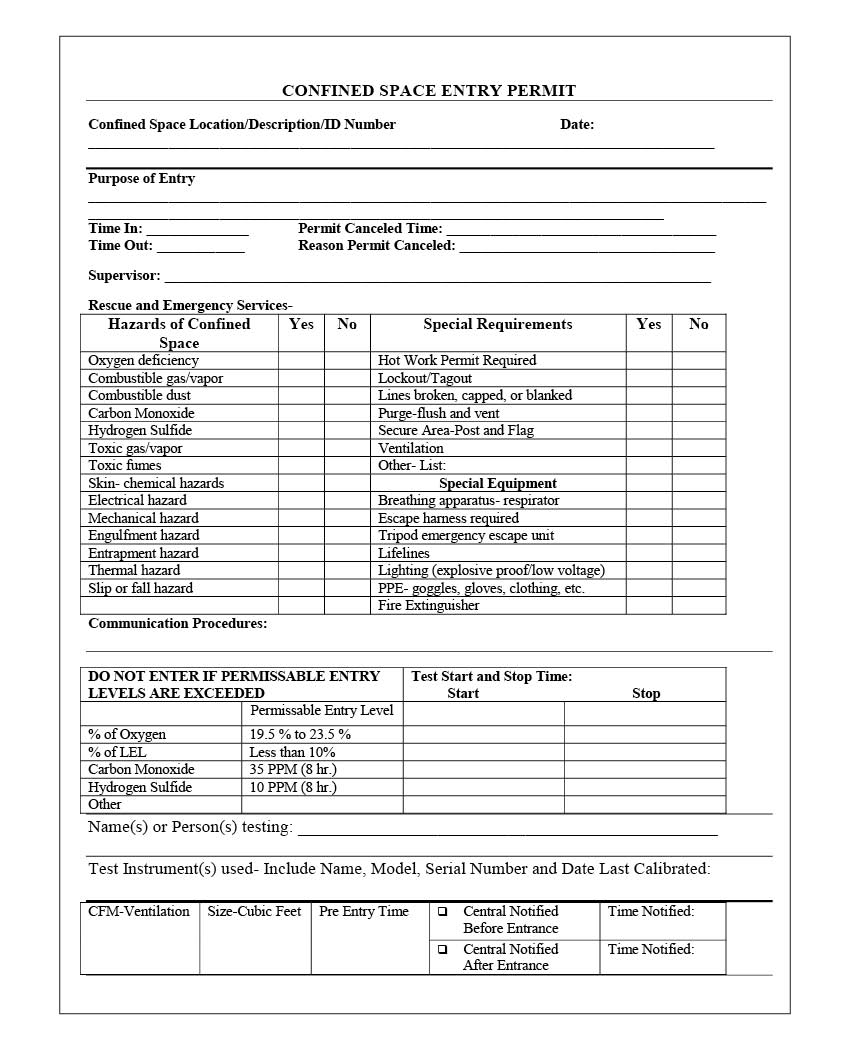

A permit must be built into the confined space policy, and there are many versions of a permit-required confined space (PRCS) permit on the internet. OSHA provides resources on developing a program, or a health care facilities manager can reach out to someone qualified within their organization or to a third-party safety company certified in confined space program development. A copy of a confined space permit downloaded from OSHA’s website is shown on the right.

A big deal

Some health care facilities professionals may think “health care facilities do not have confined spaces” or “it isn’t a big deal.” Yet, according to data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1,030 workers died from occupational injuries involving a confined space from 2011 to 2018.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 80% of fatalities happened in locations that previously had been entered by the same person who later died. Only 7% of locations had warning signs indicating they were confined spaces and 65% of confined space fatalities were due to atmospheric hazards. However, confined space fatalities can be avoided through a comprehensive confined space program that includes routine training and a systematic approach to confined space entry.

There are many overlooked spaces both inside and outside health care facilities that meet the criteria to be classified as a confined space as well as a PRCS. To determine this, health facilities professionals must first understand what a confined space is and then perform a survey. Should the results of the survey reveal confined spaces, facilities professionals then must determine whether any of the confined spaces also are PRCSs. Then, they must develop a confined space program.

The program must include a policy; an inventory; and a pre-entry, entry and post-entry plan. It also must include a training and competency program that involves training a confined space rescue team. In fact, more than 60% of confined space fatalities occur among would-be rescuers. Therefore, a well-designed and properly executed rescue plan is a must.

Confined spaces that health facilities professionals may encounter throughout a facility might be in the form of an air handler, a crawl space, a pit or a tunnel that cannot be exited without using stairs or a ladder. Other examples include openings as small as 18 inches in diameter, a place difficult to enter with a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) or other life-saving equipment, an area where the opening makes it difficult to remove a downed worker in a folded-up or bent-over position, and even openings that are larger than 18 inches but have cluttered exit paths due to the presence of ladders, hoists and other equipment.

Another defining characteristic of a confined space is one where there is a lack of air movement in and out, which can create an internal atmosphere different than the surrounding atmosphere. In such a situation, deadly gases could be trapped inside, and organic materials could decompose, causing a lack of oxygen due to the presence of other gases or chemical reactions.

A confined space is not designed for continuous worker occupancy nor to be entered and worked in on a regular basis. It may be designed solely to store a product, enclose materials or processes such as a pipe chase or utility tunnel, or transport products or substances. It may be designed for occasional worker entry for inspection, repair, cleanup and maintenance. Communication may be difficult to maintain as individuals on the outside may not be able to see or hear the people inside.

A PRCS is a space that contains or has a potential to contain a hazardous atmosphere, has the potential risk of engulfment by material or an internal configuration (walls that converge inward or floors that slope downward and taper into a smaller area) that could trap or asphyxiate a worker, or has the risk of other physical hazards (such as machinery with moving parts or the potential for shock, burns, explosion, drowning or heat stress).

A PRCS meets all the definitions of a confined space but, because of additional hazards that cannot be eliminated, a permit is needed, as is training for staff to safely work in the space, as well as attendants, a supervisor and a rescue team immediately outside the space to help monitor the hazards and entrants until work is completed.

Confined spaces that may exist at a health care facility include tanks, manholes, wells, cold storage areas, pipelines, silos, hoppers, vessels, boilers, reactors, extraction towers, separators, sewers, tunnels, pits, turbines, ducts, water mains, wastewater lines, waste ponds, cooling tower basins, roof cavities, drains, cargo holds, shafts, gas holders, bulk containers, filter housings, open ditches, vaults, culverts, air handlers, sewer manways, bulk tanks, underground storage tanks and trenches. These also may be designated as PRCSs.

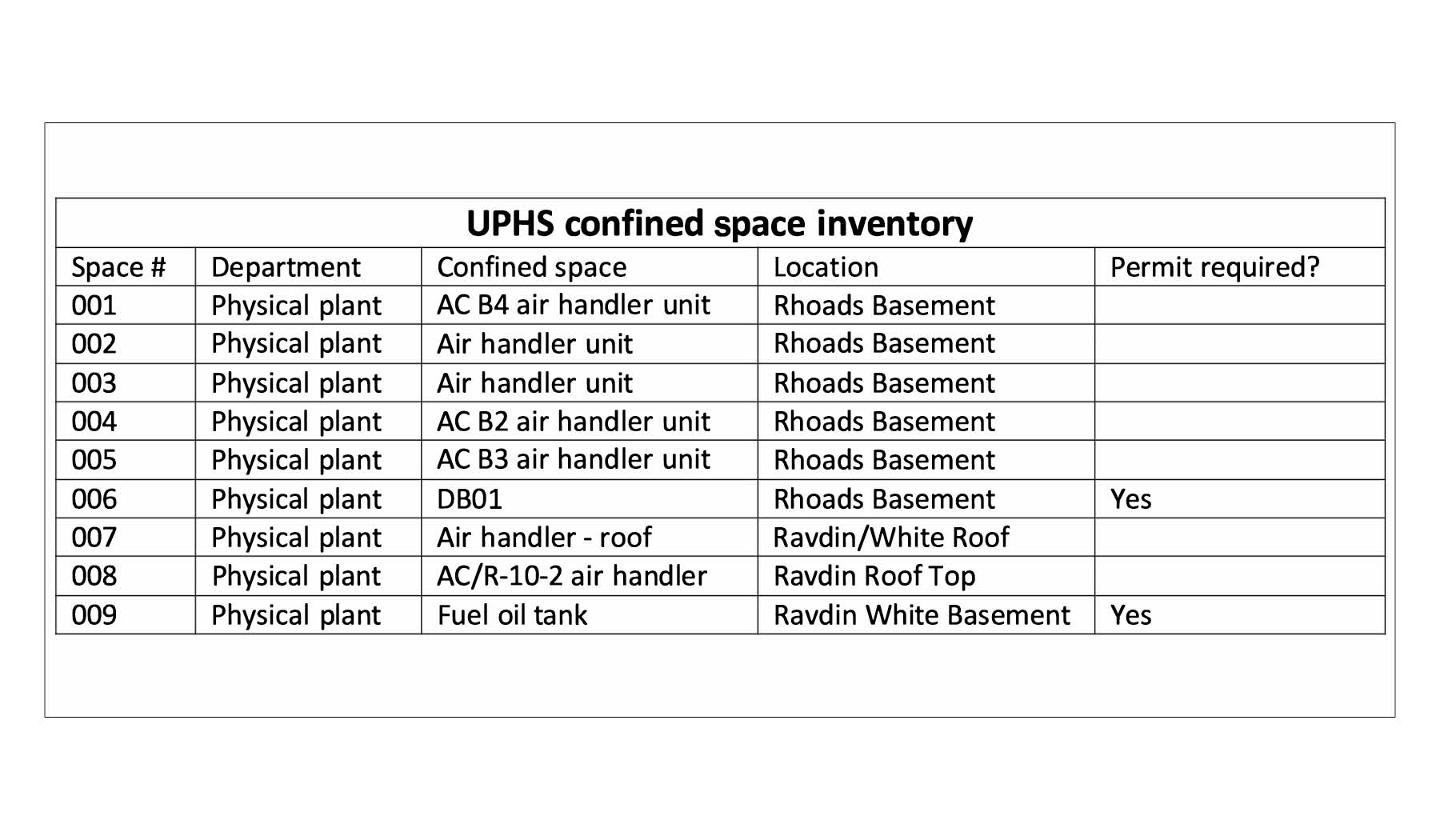

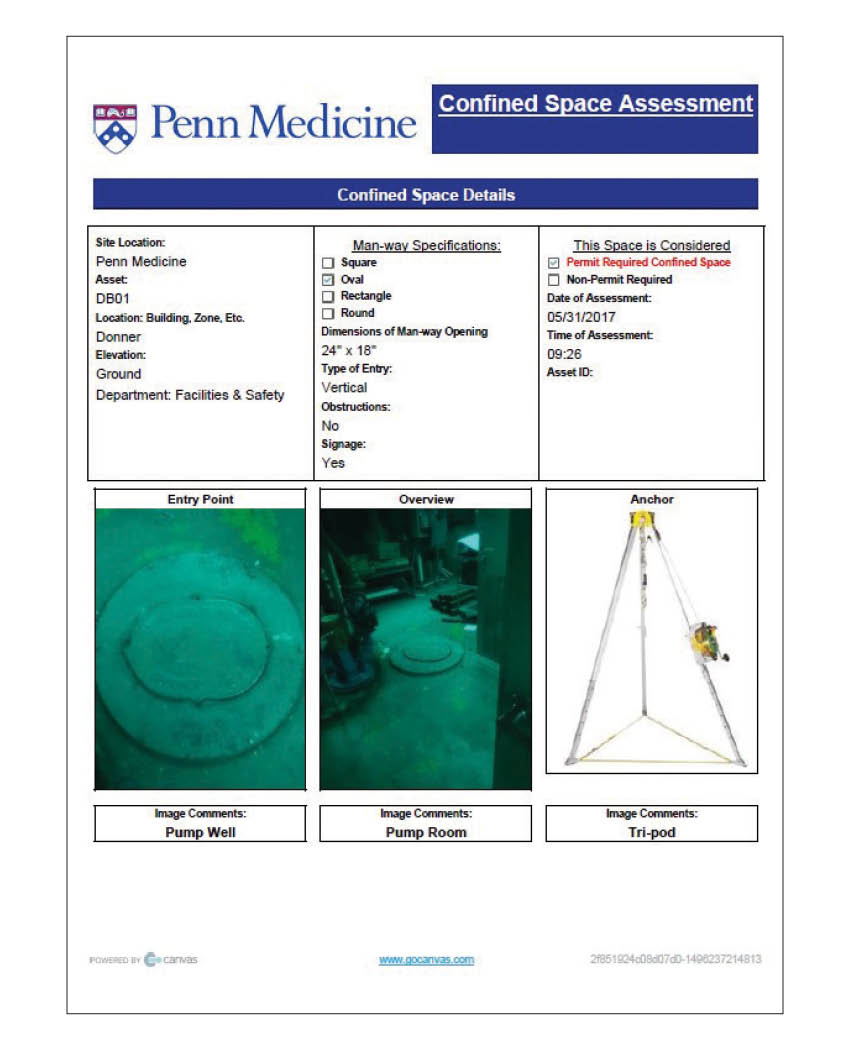

When surveying for confined spaces, it must be determined if each area is a confined space or a PRCS. This can be accomplished through performing a pre-plan confined space assessment walkthrough at the facility. A good practice is to label the confined spaces with barcoded warning labels after the survey to maintain an active inventory. An example of a confined space pre-plan assessment can be found in the “Confined space assessment” graphic on right.

Upon completing the confined space pre-plan assessment, policies and procedures must be developed for the program that include the assessment and inventory, personal protective equipment (PPE) or other equipment required to enter the space, a list of the various roles and responsibilities for confined space workers, and the training and maintenance program for the location.

The equipment list may include gas monitors, blowers, blower ductwork, tripods, harnesses, breathing air equipment (e.g., SCBAs, air lines and respirators), hard hats, safety glasses, safety goggles, vests, manhole guard rails, tents, explosion-proof intrinsically safe equipment and radios.

General awareness training for all employees and confined space entry training for workers who will work in and around the confined space must be developed. Confined space training should include eliminating or minimizing known hazards, such as locking and tagging out electrical sources and shutoff valves, blanking and bleeding pneumatic and hydraulic lines, disconnecting mechanical drives and shafts, securing mechanical parts, and blanking off sewer and waterflow.

Confined spaces that may exist at a typical health care facility.

Images courtesy of the authors

When health facilities management professionals cannot eliminate the hazards within the PRCS, filling out a PRCS permit will provide guidance on when a rescue team is needed. A rescue team’s only specific duties are to help monitor the safety of the workers and rescue the entrants should the need arise. A local fire department cannot be used as a rescue team because a rescue team must be on-site at the entrance to the PRCS for the entire duration that the space is being occupied.

The health care facility must train the facilities management and any service or construction personnel on the new process and the PPE and equipment involved, including, if applicable, a hands-on demonstration of using the confined space equipment. This should occur both initially and annually.

While the sign on top only warns that an area is a confined space and may be difficult to enter or exit, the sign on the bottom warns that an area is a PRCS and staff may enter only after filling out a permit, taking identified precautions and having the right team to assist.

Images courtesy of the authors

An employee should never enter a confined space without proper training, permit approval, equipment and support personnel. There are two different types of confined space training: (1) general awareness training for all employees, and (2) confined space entry training for employees who will work in and around the confined space. They may not be combined, nor can one replace the other. PRCSs should never be entered without permit approval, correct training and equipment as well as support personnel.

Staff who work in confined spaces are called “entrants.” They should be trained to know the spaces’ hazards, including the mode of exposure and the signs, symptoms and consequences of exposure. Facilities managers should use appropriate PPE, maintain communication with the PRCS team, exit the space when instructed or when an alarm is activated, and alert the attendant of any hazardous conditions.

Attendants assist the entrants’ work, are situated outside the PRCS and are trained to remain directly outside the space unless properly relieved, perform no-entry rescues when specified by employer’s rescue procedures, know existing and potential hazards, maintain communication with the PRCS team, order evacuation when any safety concerns arise, summon rescue or other emergency services, ensure all unauthorized persons are removed and not allowed to enter the space, and perform no other duty that may interfere with attendant duties.

The supervisor is a competent person who is responsible for the PRCS operations, is situated outside the PRCS and is trained to recognize hazards and minimize or eliminate them; alerts entrants, attendants and the rescue team of the presence of hazards and warning signs; meets training requirements for all pretesting and continuously monitors work conditions, such as atmosphere quality (using continuous ventilation when possible); signs the permit for the work in the PRCS; is responsible for ensuring the entry operations remain consistent with the terms of the entry permit and that acceptable conditions are maintained; verifies all entrants; maintains worker count by using a sign in/out form; allows only qualified and authorized entrants to enter the PRCS; removes unauthorized entrants; maintains communication with PRCS team; terminates the entry and cancels the permit as required; and verifies that rescue services are available.

Rescue team members are trained to know the hazards of the PRCS and, where a flammable or combustible material presents a fire hazard, station a fire crew in full protective gear with a backup hose line at the entrance to the confined space; wear, store and use suitable and properly maintained PPE; know emergency rescue procedures; are trained in the use of emergency rescue equipment; and maintain communication with the PRCS team.

Any time space conditions change, the team evacuates and then will reassess to determine if the area is safe to work within the confined space.

Confined space training must occur prior to initial work assignment and retraining must occur when job duties change, a change in the permit or confined space program occurs, new hazards are present and/or when job performance indicates deficiencies.

It also is the health care facility’s responsibility to ensure that contractors and service vendors can safely perform work within the confined space by reviewing contractor/vendor staff training records, verifying the correct equipment is available and used, and the contractor/vendor has their own permit to enter the space.

An example is a service tunnel that is a PRCS containing a sprinkler and fire alarm system that needs to be tested quarterly or annually by qualified professionals. A new permit is required each time the contractor/vendor must enter the space to perform the inspections.

Health facilities managers and safety professionals can, and should, ask for documentation of training for the contractors entering the confined space. It is wise to require outside contractors to provide and document annual refresher trainings. Health facilities professionals should remember to ask for a copy of the completed, filled-out permit. Finally, contractors should bring their own equipment when working with confined space.

A vital means

A confined space program is a vital means of ensuring everyone working both inside and out of health care facilities can do so in a safe manner and will go home at the end of the day to return to work another day.

OSHA data reinforce need for confined space programs

Not only is a confined space policy the law and the right thing to do, health care facilities simply can’t afford to not have this basic program to provide a safer work environment. The following statistics illustrate this point:

- The deaths of workers in confined spaces constitute a recurring occupational tragedy; approximately 60% of these fatalities involve would-be rescuers who themselves were killed. To avoid these and similar situations, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires programs, policies, training, inventory, signage, pre-plan prep and more.

- According to the opening paragraph on OSHA’s cover page for citation and notification of penalty: “This Citation and Notification of Penalty (this Citation) describes violations of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. The penalt[ies] listed here [are] based on these violations. You must abate the violations referred to in this Citation by the dates listed and pay the penalties proposed, unless within 15 working days (excluding weekends and Federal holidays) from your receipt of this Citation and Notification of Penalty you either: call to schedule an informal conference … or you mail a notice of contest to the U.S. Department of Labor Area Office … Issuance of this Citation does not constitute a finding that a violation of the Act has occurred unless: there is a failure to contest as provided for in the Act or, if contested, unless this Citation is affirmed by the Review Commission or a court.”

- OSHA has the authority to fine a health care organization in the following dollar amounts for Serious Violations, Other-Than-Serious, and Posting Requirements: $14,502 per violation; failure to abate: $14,502 per day beyond the abatement date; and willful or repeated violations: $145,027.

There are many great tools, tips and business partners that can help organizations develop and implement a confined space program.

One means of offsetting the cost of a confined space program is to reach out to an organization’s risk manager to determine if a hospital or health system’s insurance provider will partially or fully fund bringing in a vendor to assist with the program. This type of partnership could help an organization quickly and successfully implement a great program.

About this article

This is one of a series of monthly articles submitted by members of the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s Member Tools Task Force.

Shadie (Shay) R. Rankhorn Jr., SASHE, CHFM, CHC is the senior director of facilities management at Quorum Health and president

of the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE); and Jeffrey Henne, FASHE, CHC, CHSP, CHEP, CHFSM, is the safety and emergency manager for the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and a past president of ASHE. They can be reached at srankhorn@qhcus.com and jeffrey.henne@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.