When Hunterdon Medical Center in Flemington, N.J., saw an outbreak of a new mutated strain of Clostridium difficile in 2004, environmental services (ES) and infection prevention leaders quickly responded.

When Hunterdon Medical Center in Flemington, N.J., saw an outbreak of a new mutated strain of Clostridium difficile in 2004, environmental services (ES) and infection prevention leaders quickly responded.

Targeted cleaning protocols were implemented in rooms of C. difficile patients and different cleaning and disinfectant products were specified. Cleaning practices were monitored closely as the ES and infection control directors continued to make rounds together, regularly sharing ideas for ways to reduce the chances of spreading the infection. Training ES and clinical teams and monitoring cleaning practices remained constant focal points. Together, these and others steps made a difference.

"We use control charts and we certainly saw the numbers come back into range, but since that time we've seen the C. diff numbers drop each year," notes Kathy Roye-Horn, R.N., CIC, director of infection prevention at the facility.

Similar reductions occurred with health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cases at the 178-bed facility, which has nearly 400,000 square feet of cleanable space. Driving down incidences of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus initially proved more challenging, but those numbers, too, have come down, Roye-Horn says.

She and Marita Nash, CHESP, director of environmental services and linen, believe the ongoing collaboration of their departments and the inclusion of clinical and patient transport volunteers in equipment cleaning protocols have contributed significantly to the steadily improving results. Other more recent steps they've taken include:

- developing a detailed cleaning sequence for the ES team to follow;

- implementing adenosine triphosphate surface hygiene testing to provide an objective indication of cleanliness of high-touch areas in patient rooms; and

- establishing standards for minimum cleaning times for occupied rooms and terminal cleaning of rooms of discharged patients.

Increasing collaboration

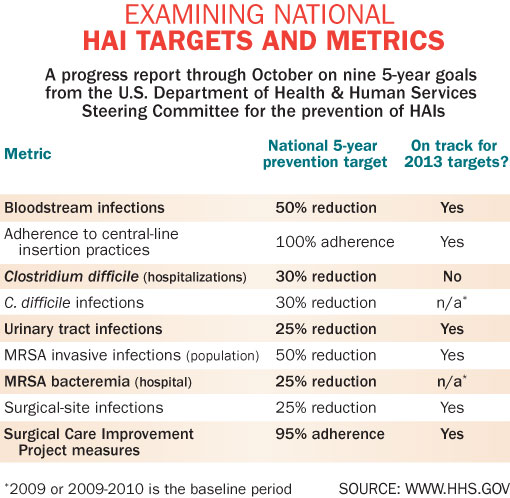

If hospitals are going to continue making progress in reducing health care-associated infections (HAIs), many experts believe it will be because of the kinds of coordinated approach institutions like Hunterdon Medical Center have taken. In short, expanding collaboration with clinical and nonclinical staff, deploying evidence-based tools to monitor cleaning thoroughness, developing comprehensive cleaning and disinfection guidelines and resources for ES staff, and continuously updating training and educational programs all will be essential as hospitals continue to reduce HAIs and readmissions.

Patti Costello, executive director of the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE), says there are many ways collaboration can be improved in fighting HAIs. This starts with recognizing and implementing best cleaning practices and guidelines and grasping the larger value of the ES department to the institution.

"Today, it's how satisfied are your patients? Satisfaction and readmissions hang in the balance over whether your facility ultimately will be reimbursed," Costello notes.

Over the past decade there has been a greater appreciation for the link between the health care environment and infections. Studies show that patients contaminate 20-30 percent of their environment and that pathogens can remain in place for extended periods without being removed, according to William Rutala, Ph.D., MPH, CIC, and director of hospital epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Health Care System in Chapel Hill. Rutala shared this point during a panel presentation at the AHE annual conference in September. He added that as government and accrediting bodies increase scrutiny, hospitals will need to pay closer attention to environmental cleaning.

Just how significant the threat of disease transmission is in the patient care environment again was underscored in a study released in November on multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDR-AB). The study in the American Journal of Infection Control (AJIC), a publication of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), noted that MDR-AB was found in the environment of 48 percent of the rooms of patients colonized or infected.

The research found that supply cart drawer handles (20 percent), floors (16 percent), infusion pumps (14 percent), ventilator touch pads (11.4 percent) and bed rails were most commonly contaminated, and 85 percent of the environmental cultures matched the strain of the infected patient in that room. These results are of particular concern due to the frequency with which health care workers may touch infected surfaces during patient care.

One byproduct since the research was conducted: New strategies to reduce transmission of the pathogen have resulted in a significant decrease in infections and acquisition.

More tools needed

It's examples like this that lead many experts to believe that the focus needs to be on developing additional educational and training tools for ES teams, clinical and nonclinical staff. A survey conducted jointly by AHE and APIC in August found that infection prevention and environmental services professionals believe there is a need for more education and resources to prevent HAIs.

More than half (51 percent) of the 2,000-plus survey respondents (79 percent of whom work in hospitals) find it difficult to locate useful resources about proper cleaning and disinfection. About six in 10 respondents believe educational resources on cleaning, disinfection and infection prevention and control should be directed to hospital executives as well as to physicians.

APIC and AHE leaders aim to help meet this need through a program they jointly created titled "Clean Spaces, Healthy Patients." The program will incorporate educational resources, training materials and other HAI-prevention solutions. Visit www.apic.org/cleanspaces for more information.

Ruth Carrico, Ph.D., R.N., CIC, and a clinical advisor to AHE, says the tools produced for the program will meet important needs.

"These survey results indicate that we can make improvements to ensure that the environment in which care is rendered helps to combat infections," says Carrico, who is an associate professor at the University of Louisville (Ky.) School of Public Health and Information Sciences. "Strengthening collaboration between infection prevention and environmental services staff will advance this goal and contribute to reducing infections and improving patient outcomes."

Of course, getting the resources to ensure adequate budget and staff for training and education or to enact evidence-based cleaning audit systems likely will become increasingly difficult for many ES teams over the next several years, particularly with hospitals experiencing declining reimbursement rates under the Affordable Care Act. But Roye-Horn argues that infection prevention and ES leaders need to make their case to administrators and stress the value of these efforts.

"I think facilities can make a strong case for why they need to audit in a different method than observation… Science has shown that touchable surfaces transmit [bacteria] to patients and that they can get infections from them," says Roye-Horn. She recommends ES and infection prevention leaders work together to educate hospital executives about the costs associated with HAIs and the money that can be saved through prevention when there are adequate staffing and standards in place for the minimum resources required to achieve objectives.

Roye-Horn and Nash successfully lobbied senior executives during tight fiscal times in the 2004-2005 budget year for more full-time equivalents (FTEs) to ensure compliance with the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee guidelines that had come out a year earlier.

"We tried to put a dollar amount on the infections that we saw so that they could understand how costly they were, because there seemed to be a deficit at the time," Roye-Horn says. "We tried to make the case that it was cheaper to put more staff in place to prevent these infections than it was to continue to have this isolation [of patients] and these infections."

Nash performed some time-work studies and determined how many FTEs would be needed for adequate high-touch surface cleaning. She says as she shared this information with administrators, the nods of ascent from the chief financial officer made it clear the message was received. The teams didn't get everything they requested, but they got what they needed.

Judene Bartley, vice president of Epidemiology Consulting Services in Beverly Hills, Mich., and a clinical consultant for the Premier Safety Institute, believes engaging top-level executives in infection-prevention resource needs for cleaning and verifying results will grow in importance in the coming months and years.

"Everybody needs some level of higher authority in senior leadership to get excited about this as it relates to the Affordable Care Act, because now Hospital Compare will be publishing HCAHPS scores and it's going to be an important point for hospitals to be able to say that we have data to show we have a clean hospital," Bartley says. She further notes that an objective review of possible cleaning measurement tools has been published in AJIC's free June 2010 supplement on the environment.

AHE's Costello believes properly employing measurement tools will help ES and infection-prevention leaders to improve results so that data about quality continue to move in the right direction.

And rather than getting too focused on which type of measurement system may yield the best results, Costello is concerned that ES leaders concentrate on using the findings in the right way.

"If you're going to use any of these tools for quality measurement, it needs to be used as a training tool," Costello says. "The vast majority of the people I know who have used them have found that the employees get very excited when they see the outcome of their work."

Bob Kehoe is the associate publisher of Health Facilities Management.