A nurse supervisor is shot trying to stop an 85-year-old patient who opens fire in a Danbury Conn., hospital this past March. A 77-year-old man visiting his elderly wife in a Winter Haven, Fla., hospital in May as she recovers from a stroke fatally shoots her and then kills himself. A 26-year-old man is arrested in 2008 and charged with assault and battery after he punches a triage nurse in the face and throws her against a wall in a Massachusetts hospital, angry about his wait for service.

These real-life examples are indicative of a trend in which violent crimes are occurring in increasing numbers in U.S. hospitals and other health care settings. To address the problem, The Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert in June to remind all hospitals that maintaining a safe environment requires increased vigilance.

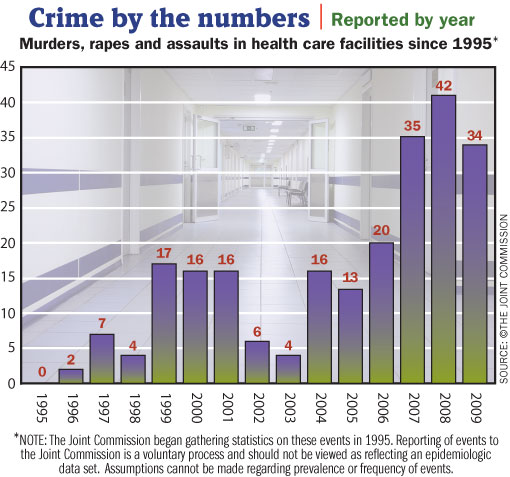

According to The Joint Commission's Sentinel Event Database, there were 256 homicides, rapes and assaults of patients and visitors in U.S. health care facilities since 1995. There has been a surge of violent crimes in hospitals since 2004, with 110 incidents having occurred since 2007, the alert states.

The number of violent crimes in health care facilities is likely even higher. The Joint Commission believes there is significant underreporting because hospitals are not required to report the cases, says Mark Chassin, president, The Joint Commission.

Russell L. Colling, a health care security consultant in Salida, Colo., and an advisor to the Sentinel Event Alert, cites several reasons why violence in hospitals is rising. For instance, a lack of psychiatric care for the mentally ill has caused many to get help at hospitals, where they become violent, he says.

Crowded, understaffed EDs create high-stress situations where violence can occur, he adds. Emergency patients who are drug and alcohol abusers only add to the problem.

A hospital's 24/7 operating hours also makes it vulnerable and creates special challenges for securing buildings and grounds. "A key to providing protection to patients is controlling access," Colling says. It's also critical that all staff remain vigilant at all times about the identity of a person who is trying to enter a facility or who has made his way onto a patient floor. That means staff need to ask questions if they feel suspicious.

Though less common, hospitals also need to be alert to the potential for violence against patients by health care staff. The Sentinel Event Alert points to the need for human resources to be alert for warning signs of staff behavior that could elevate the risk of violence toward a patient. Criminal background checks should be conducted on all new hires whenever possible, and especially on those who work in high-risk areas.

The Sentinel Event Alert points out several other steps facilities can take to prevent violence. Among them are evaluating the facility's risk for violence by examining the campus and taking extra precautions in the ED, especially if the hospital is in a high-crime area or one with gang activity. Hospitals need to encourage staff to report incidents or threats and for administrators to take those reports seriously.

Despite the rise in violence at hospitals, Chassin says he believes that health care facilities in general do a good job of providing security, especially considering the challenges they face. "Hospitals are in a very difficult position because they have to balance the absolute need for access to their facilities for families and visitors against these rare but catastrophic calamities when somebody commits a violent action," he says.

The alert is available at www.jointcommission.org/sentinelevents/sentineleventalert/sea_45.htm.