|

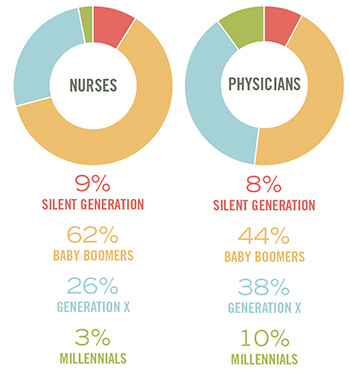

| SOURCE: NURSING DATA FROM AMERICAN NURSES ASSOCIATION FACT SHEET, 2011; AND PHYSICIAN DATA FROM AMA PHYSICIAN MASTER FILE, 2012. GRAPHIC COURTESY OF BALLINGER |

Today’s multigenerational workforce has a wide range of needs, varying working styles and often differing priorities.

Staff at most health care institutions span a range of generations — historically from the Silent Generation to baby boomers and Generation X and, rapidly, millennials (also known as Generation Y) and beyond.

When developing new health care facilities, design professionals can address the priorities of this evolving workforce through an inclusive planning and design process, which responds to the needs of the entire constituency.

Generational preferences

How can architects help to mediate the interests of all stakeholders and provide flexible spaces to accommodate the rapidly changing needs of staff and patients?

You may also like |

| Researched solutions for health care interiors |

| 2014 Health Facility Design Survey |

| Caregiver station finishes and furnishings |

| Designs for safe patient handling |

| |

To plan and design for the health care workplace, designers first must understand how these generations work as individuals and how they interact with other generations.

Baby boomers, who typically appreciate commitment and teamwork, have been trailblazers throughout their lives. Gen Xers have a self-directed working style and strive to find a work-life balance. Millennials are considered digital natives and, thus, more comfortable with using technology in all aspects of their daily lives.

When designing health care spaces for this multigenerational workforce, designers must consider each approach and strike a balance that not only allows the work environment to flow, but also takes advantage of new developments to improve the overall care delivery model. These spaces need to be responsive to differing generational perspectives and, more importantly, flexible to adjust over time to workforce evolution.

For example, electronic health records (EHRs) have resulted in different impacts and optimal spaces for clinical care depending on the typical user. The decentralized station, the central station and in-room charting all have taken on different roles and there appears to be a generational preference for the variety of spaces.

In recent post-occupancy evaluation surveys of nursing work patterns, architects from the design firm Ballinger in Philadelphia explored the generational preference related to which staff chose to work at a decentralized station vs. a central station, or to chart in the patient room.

Those from the baby boomer group were two times more likely to use the decentralized stations over their millennial and Gen X peers. Additionally, they selected the charting station in the room a mere seven percent of the time. In the survey, there was a clear preference for the decentralized station with its direct patient sight lines, proximity to the patient and, potentially, a reduction in travel distances.

The Gen X group was 30 percent more likely to work at the central station than the baby boomers or millennials, which demonstrates their preference for a strong peer network and collaborative work style. They also chose the charting station in the room 22 percent of the time, significantly more than their baby boomer peers. This suggests an increase in willingness to chart in front of the patients.

The millennial group appeared to spend 12 percent less of their shift charting than the baby boomer and Gen X groups, indicating that their status as digital natives may allow them to simply chart faster. Additionally, the millennial group used the station in the room 26 percent of the time they were charting, more than either their Gen X or baby boomer peers, alluding to a comfort level of the digital connection in the patient’s presence.

Sociologist Barry Wellman coined the term “networked individualism” to describe the way loose-knit networks of people — especially millennials — are overtaking more tight-knit groups and large hierarchical bureaucracies. This notion of networked individualism influences the work space and preferences of evolving generational groups. It is no longer a single office or a large open nurse station, but rather a touchdown station in a collaborative team room that gives the caregiver temporary spaces to make their own.

The impact of the increased variety of spaces requested by the clinical care team, and their effect on the design of the patient floor, transforms the traditional nurses’ station into a greeter function and a public face while the main activity of the station is screened from the public view.

At Reading Hospital’s 7th Avenue Building in West Reading, Pa., a decentralized station is located outside of every pair of patient rooms to increase sight lines to patients. Frequently accessed supplies also are decentralized between every pair of patient rooms to provide easy access to personal protective equipment and limit nurse travel distances. Collaborative worktables, integrated with computers and monitors, allow clinical staff to work together more effectively to treat patients. These collaborative spaces are enclosed and located behind the greeter to protect patient privacy and sound transmission into the patient rooms.

Rounding groups, which incorporate physicians, residents, nurses, a social worker, pharmacist and other ancillary personnel, can sit together in the team rooms and discuss a chart on a large-format screen and, collectively, evaluate the impact of all care activities. More experienced nurses can sit with millennial nurses in the team space and give them feedback, all with access to patient EHRs. The team collaborative space is easily accessible and provides the necessary technology and space to facilitate these interactions.

|

|

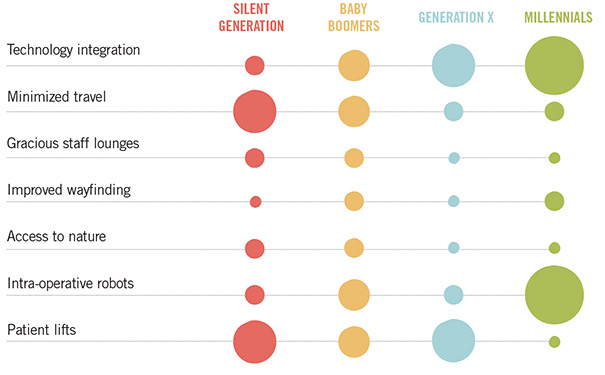

This graphic from Ballinger illustrates the different focuses of the various generations as they relate to each other. |

Multigenerational elements

According to a 2014 survey by the Center for Health Design, top concerns for health care providers and designers are the effect of new technology on facility design, use of the environment to build and improve staff culture, and reduction in operating costs. Design elements within health care are evolving not only to address generational concerns, but also to provide a better environment for care.

As the generational profile of the workforce continues to blend, there is a potential disconnect between the multifaceted needs of this workforce and the trajectory of progressive health care design. For the older generations, there is a greater importance on easing the physical demands of work to deal better with longer working hours.

Decentralized nursing stations grew out of the evolution of all private rooms as the new standard, which significantly increased the size of a typical nursing unit. Nursing staff could no longer see the patients from a central station. The decentralized stations were created based on initial evidence-based design results, suggesting that increasing care at the bedside improves patient outcomes. Ballinger’s research supports that nursing staff, particularly the baby boomers, prefer to utilize the decentralized station with their proximity to the patient. One outcome of the larger bed floors is that caregivers are walking long distances to remotely located supplies.

To offset this inefficiency and strain on the caregivers, there is now a shift to decentralize supplies as well. The goal of this change is to minimize walking distances and reduce travel time for the caregiver, and collocate the charting station, the caregiver and the frequently accessed supplies closer to the bedside.

Generation X, on the other hand, prioritizes collaborative space and, therefore, a more centralized model. This is potentially attributed to the generational aversion to hierarchy and more informal work groups. The collaboration station and team space give equal footing to all generations to work together.

Millennials are more comfortable with the use of technology in the workplace, making new developments such as intra-operative robots and the multitude of wireless and handheld technologies part of and beneficial to their working style. One baby boomer surgeon recently referred to his “Nintendo colleagues” regarding their preference for new robotic technologies.

This growth of technology is altering the infrastructure that buildings need to support them. As equipment such as IVs and blood pressure cuffs evolve, they include new computer technology that will allow the equipment to talk directly to the EHR. To support these technological advances, buildings today must be equipped with robust dual-fiber networks and distributed antennae systems. The low-voltage and teledata infrastructure now rivals the cost of the mechanical and electrical systems from an infrastructure perspective.

There are certain components that are integral to providing the best design, and there are additional elements that are proven to be beneficial in a healing environment. A better understanding of the priorities and needs of the workforce can inform the integration of these elements, creating more effective and efficient spaces.

Some aspects of health care design, however, resonate with all generations. Increased natural light in both staff and patient spaces, access to nature and dedicated staff support spaces can be incorporated universally into facility design to improve the work environment. For Lancaster (Pa.) General Health’s new Ann B. Barshinger Cancer Institute, the design included a meditation area for both staff and patients to be able to step out of the work day and decompress.

Ultimately, outcomes from a design process that considers the differing generational perspectives will contribute to a better overall patient care model.

Planning for uncertainty

Because new technologies and the changing health care delivery system are having such an impact on today’s facility design, a well-orchestrated planning and design process is essential in navigating future uncertainty.

Increasingly long project timelines and construction processes add another layer of complexity; it is not uncommon for a large health care project to take five to seven years from concept to occupancy. When this timeline is compared with technology leaps that typically take only two to three years from inception to adoption, it is evident that change outpaces the design and construction duration.

From the time of initial design to the move-in date, technology has made dramatic changes and advancements. This same timeline can affect who is in charge; it may be one set of leaders today and a new set of leaders — potentially even from a separate generation — who occupy and use the facility on opening day and beyond. The design team must anticipate these changes, provide a level of design flexibility to accept the variations prior to move-in, and provide parameters for solutions with longevity.

A key success factor in the early planning and design stages is to engage the appropriate mix of stakeholders. This initial planning team is responsible for shaping the project and anticipating what technology and generational drivers might do to the environment of care both prior to move-in day and as the facility ages. The team also must evaluate the needs of all participants and provide a variety of spaces to accommodate focused and collaborative work, maintain privacy for sensitive patient information, and increase interactions across departments and across generations.

The more diversity and occasional conflict of opinion expressed in the design group, the more valuable the insights. Multiple generations offer a variety of vantage points to test design solutions, which facilitate the design team’s ability to respond appropriately to the needs of all stakeholders. How can designers address digital natives and also make accommodation for those who may not be as comfortable with the latest technology to work in the same unit?

Empowering staff

An inclusionary design process empowers current staff as part of the program, and brings valuable vantage points to the discussion. The generational variety of the group can build an even greater consensus, and can yield the best design and reduce staff turnover.

Nurse turnover can have a dramatic effect on a hospital’s operating margin. For example, “the average cost of turnover for a bedside nurse ranges from $44,380 to $63,400 ... Each percentage change in nurse turnover will cost the average hospital an additional $359,650” per year, according to an article in the November 2005 issue of Hospitals & Health Networks. This can be compounded with the new HCAHPS scores’ effect on reimbursement models because medical staff job satisfaction has been found to correlate with patient satisfaction.

When turnover has this kind of impact on the bottom line, it is in the hospital’s interest to invest in areas that will help staff retention. Facilities that are designed to comprehensively address multiple generations lead to a more efficient and satisfied workforce. When the workforce has the tools to perform its duties effectively, patient care sees improvement. When the model for patient care improves, patients and families have a more positive experience — the ultimate triumph for any hospital.

Louis A. Meilink Jr., AIA, ACHA, is a principal and Christina Grimes, AIA, LEED AP, EDAC, is a senior associate with the firm Ballinger in Philadelphia. They can be reached at lmeilink@ballinger.com and cgrimes@ballinger.com, respectively.

Planning for the millennials

This year, the millennial generation is projected to surpass the baby boomers as the nation’s largest living generation, according to the population projections released by the U.S. Census Bureau in April.

Millennials, defined as those between 18 and 34 years are projected to number 75.3 million, surpassing the projected 74.9 million baby boomers (ages 51 to 69).

This shift in demographics to a millennial plurality has a corresponding effect on today’s workforce and on the population as consumers. In a health care environment, the growing millennial relative majority has an impact on where consumers go to receive care and how care is provided.

The challenge for architects is to plan and design spaces that accommodate health care professionals and an increasingly progressive delivery model, while continuing to address the needs of all generations, both from the patient and staff perspectives.

|

|

RENDERING COURTESY OF BALLINGER/SPINE3D Reading Hospital in West Reading, Pa., where a new operating room platform accommodates a multigenerational group of surgeons. |

Pennsylvania hospital bridges generational divide

More experienced surgeons were taught techniques which did not require computer technology, while the surgeons entering the workforce today increasingly rely on technology such as imaging capabilities, DaVinci robots or other interoperable modalities.

The millennial staff members are focused on small and large group learning that is immersive and flexible and heavily centered on emerging technology. These training techniques are then impacting the spaces needed in the clinical environment.

Compounded with the digital integration and increased technology emergence within the OR platform, the design team must work with the multigenerational workforce to design an OR platform that is simultaneously effective for experienced surgeons and those from other generational vantage points.

The new operating room (OR) platform at Reading Hospital in West Reading, Pa., combines 24 ORs, eight procedure rooms, pre-admission testing (PAT), central sterile supply and 150 new surgical patient beds to transform the patient experience by collocating the entire patient experience in a single location with a dedicated entry point.

This enables an entirely new process from initial PAT prior to surgery through the discharge at the end of care to take place in a dedicated location. The new hybrid OR rooms, and intraoperative robots within the OR, and the procedure suite included the latest technology and infrastructure to accommodate future devices.

All designed with the clinical staff in mind, this colocation of all surgical components into a single building increases staff efficiency is tied together with 83,947 square feet or nearly two acres of a healing garden and green roof for staff and patient respite to deliver an exemplary level of patient care.