Utah-based Intermountain Healthcare recently converted to a self-distribution supply chain model. In doing so, it joined some of the nation's largest integrated delivery networks in assuming greater control of product handling and managing inventory — a move that's expected to save the organization $80 million over five years.

Utah-based Intermountain Healthcare recently converted to a self-distribution supply chain model. In doing so, it joined some of the nation's largest integrated delivery networks in assuming greater control of product handling and managing inventory — a move that's expected to save the organization $80 million over five years.

The centerpiece to the transition is the 327,000-square-foot Kem C. Gardner Supply Chain Center. Opened in September, the center will house all supply-related operations — from negotiating contracts to handling and delivery of more than 2.5 million medical items to logistics. In this more centralized approach, the team will focus on innovation and boosting customer satisfaction while sharply reducing costs tied to vendor middlemen.

The $40 million highly automated center will do something else that won't show up directly on any balance sheet. It will enable the supply chain team to take greater responsibility for product ordering, distribution and stocking across the system's 22 hospitals, 185 clinics and medical group with 900 employed physicians. This will free caregivers from many of these tasks so they can spend more time with patients.

When considering the complexity of the health care supply chain in large health systems and all those involved, it makes sense to remove as many people outside the system as you can from the beginning to the end of the process, says Brent Johnson, vice president of Intermountain's supply chain.

Intermountain Healthcare's initiative is significant beyond the savings the center will generate. It's an example of how many of the largest and most powerful health systems are tying supply chain directly to their strategic mission to improve quality and value. And in the post-Affordable Care Act world, that will become increasingly important to success as rapidly expanding health systems achieve greater economies of scale.

Johnson notes that many large nonprofit networks figure they can save 5 to 10 percent with self-distribution. But that's only part of the story. The center also is designed to support efforts to improve caregiver satisfaction and deepen physician involvement in product standardization.

Strategy trumps tactics

Many industry consultants believe that for health care to transition successfully from volume- to value-based care, executives must do a better job of engaging supply chain leaders as strategic partners. They believe that in larger health systems, in particular, supply chain leaders need to have a seat at the table in C-suite strategic planning.

Eugene Schneller, Ph.D, professor and director of health sector supply chain initiatives at the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University, argues that the current supply chain infrastructure must support the operational transformation associated with the Affordable Care Act. Writing in Premier Inc.'s fall 2012 edition of Economic Outlook, he observes that hospitals are still early in this transition:

"By default, health care supply chain leaders are challenged to become change masters who orchestrate internal responses to demand-generated innovations and visionary leaders who facilitate collaboration among external suppliers in support of quality, accountability and value in patient care. While progressive managers are beginning to develop the necessary infrastructure, comprehensive processes that further clinical and business goals through supplier engagement are still in the early years."

Peggy Naas, M.D., M.B.A., vice president and leader of physician strategies for Texas-based VHA Inc., likewise sees supply chain professionals taking on steadily greater importance over the next five years. The supply chain's mission going forward should support the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's (IHI's) Triple Aim initiative, she says. IHI believes new health system performance designs must be developed to simultaneously pursue:

- Improving the patient experience of care, including quality and satisfaction;

- Improving the health of populations;

- Reducing per capita costs of health care.

Naas believes physician employment by hospitals will continue to grow as health systems further expand, largely through mergers and acquisitions. With this growth will come greater shared management responsibility opportunities with physicians.

"I think there will be deeper and continuing models of co-management. We'll see [the] supply chain have increased opportunities strategically in additional models such as clinical integration. We'll see an increased sense of health systems looking across a continuum of care and managing the transitions," Naas says.

Forging new alliances

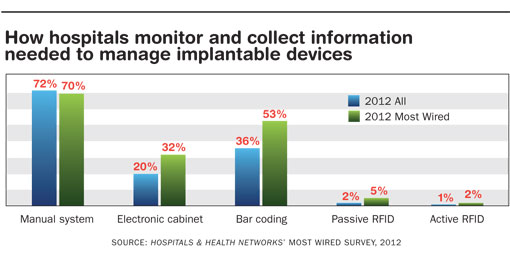

VHA has seen growing interaction in recent years among members who are willing to work across health systems to improve performance and reduce costs. They're aligning to leverage better pricing by improving product standardization in costly physician preference areas such as implantable medical devices (IMDs). IMD-related costs represent the No. 1 supply chain expense for many hospitals and networks, often accounting for 20 percent or more of total supply spending.

Yet, while many organizations have done a better job lately of engaging physicians in value analysis, product standardization and other areas to reduce IMD expenses, significant opportunities remain. To capitalize on these opportunities, hospital executives will need to set a clear strategic vision that better integrates the ways in which physicians and supply chain leaders work together.

Just how significant the opportunities are in this area was underscored in a 31-page Government Accountability Office report issued in January. The study covered prices hospitals paid for selected IMDs between 2004 and 2009. Price variation for identical cardiac devices across three product categories ranged from $500 to more than $6,000 per device.

Attacking major cost variations like this requires a multipronged strategy and perhaps new tactics such as those employed recently by three of VHA's integrated delivery network members. The systems formed the Midwest Purchasing Coalition. The coalition comprises Ohio Health in Columbus, Premier Health Partners in Dayton, Ohio, and Community Health Network in Indianapolis. In one of the initiatives, two of the three members teamed up to reduce costs associated with total joint implants without negatively affecting outcomes.

Tom Nikiel, vice president of supply networks for VHA, says the organizations engaged key orthopedic surgeons who encouraged their medical staffs to support the initiative.

"The supply chain leaders made them aware of the initiative to gain their support and together they negotiated with the suppliers as the Midwest Purchasing Coalition rather than going in individually," Nikiel explains. "By sticking together, they achieved greater savings than either of them could have individually."

The savings percentage in this case came to double digits, Nikiel says. He adds that the three-member coalition is on target to save about $15 million this year. "What we see across all of our supply networks is that when coalitions tackle a specific initiative, the savings generally average around 10 to 12 percent," Nikiel says.

Looking beyond med-surg

Opportunities to cut costs and meet the IHI's Triple Aims lie outside of med-surg supplies, too. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) supply chain team, which is responsible for $2 billion in annual spending, has found efficiency gains by automating the facilities inventory management program at one of its hospitals.

Working with a supply chain partner, Grainger, UPMC last year set out to implement a more streamlined purchasing process for items used by facilities management staff and engineers. Under the old system, facilities managers and engineers placed orders daily, often resulting in duplicate orders between shops or within the same shop. Other drags on efficiency included repetitive purchasing of items that couldn't be located quickly and hoarding parts by staff.

Edward Dudek, assistant vice president of facilities and engineering, says the KeepStock program was piloted at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh — one of 20 acute care hospitals in the UPMC system. First-year results cut costs by 25 percent for the facility team's supplies used daily, nearly eliminated emergency part runs and improved transparency in invoicing processes. Another important benefit: Repairs and replacement of everything from light bulbs to pipe fittings has become more predictable and efficient, because parts are where they need to be.

Grainger provides a dedicated rep one day per week to consult with facility and supply chain managers to see if par levels are working efficiently and whether they need to be adjusted. The rep does not sell products and earns no commission based on purchase levels.

"This was less about the money we could save than it was about freeing up staff from performing repetitive tasks such as generating purchase orders," says Elizabeth Munsch, facilities director at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Munsch and others involved in the program say facilities managers and engineers have more time to perform maintenance tasks by decreasing the time they spend on supply-related activities. That's led to greater internal customer and patient satisfaction.

From smaller, nonclinical initiatives like this one to much larger efforts that require tighter physician alignment, supply chain leaders will have to mine every opportunity in the coming five years to optimize performance.

Bob Kehoe is associate publisher of Health Facilities Management.