In a shrinking economy with limited capital, health care organizations with continuing space demands are facing tough decisions about whether to replace or renovate aging departments, buildings and entire campuses.

In a shrinking economy with limited capital, health care organizations with continuing space demands are facing tough decisions about whether to replace or renovate aging departments, buildings and entire campuses.

These demands are further challenged by the need for increased operational efficiency, service line reorganization, program growth, increased specialization, improved technology, competition for patients and better financial returns.

So, how do health facilities professionals make complex decisions about whether to replace or renovate a health care campus? A thoughtful campus planning process should accomplish the following:

• Accurately quantify the real clinical needs;

• Identify a diversity of sustainable planning options;

• Accurately price the hard, soft and hidden costs of the options;

• Analyze the trade-offs of cost, disruption, image and the value of "new"; and

• Calculate a tangible return on investment.

Elements of success

It is important to set goals for successful growth and development of space to be used as a measuring stick for assessing planning options. Following are seven elements that are vital to success:

Zoning and operations. The zoning of the campus should be clear and intuitively understandable, with adjacencies that support efficient operations. This is the initial planning diagram that determines the relationships of the individual pieces, such as diagnostic and treatment areas, patient beds, outpatient care, support services and the public.

Orientation and circulation. The movement of people, materials and vehicles should be logical, intuitive and convenient, with an obvious sense of arrival, convenient and adequate parking, a focal center of the campus, and clear and easy wayfinding connecting the pieces together.

Growth and adaptability. There should be a logical method for expanding the campus, allowing for flexible planning and phased, incremental growth. This is often a challenge at older, established medical centers in urban settings and raises the question of whether to relocate to a space with more room to grow.

Patient and family focused. The integration of family is an important component in the larger picture of patient care. Facilities should accommodate families with learning environments, diversion and delight, spaces for children, and a sense of safety and security.

Sustainability. To preserve our natural resources, our buildings should conserve energy, responsibly reuse materials and be built only on sustainable sites. A more careful selection of sites will preserve existing natural sites. A more sophisticated look at building envelopes and the integration of HVAC systems will require less energy to heat and cool, a cost that has exponential importance over the life of the building. And a more careful look at materials reuse will reduce initial capital costs while conserving our natural resources.

Market share. What improvements or programs can expand reach, attract the best medical talent and grow patient volumes? How can these programs be enhanced either through new or renovated construction? Will new technologies demand new space or can they be accommodated in existing structures and their respective infrastructures?

Cost. Finally, all costs should be considered, including initial construction, phasing, financing, fees and, most importantly, the long-term operational costs of maintaining the space. Institutions too frequently look at the first costs of construction without analyzing the long-term implications of these decisions. This often is a case of capital and operating budgets not being integrally linked in a causal way. Those responsible for planning and building health care facilities should be integrated fully with those responsible for operations.

Once overall goals have been established, various options for campus growth should be created, looking at the full range of renovation, renovation and addition, and full replacement options with an eye to the goals previously listed.

A matrix can be developed to analyze all the factors. Each institution will have a different planning approach with corresponding goals. In the end, though, cost often becomes the crucial factor in determining the right solution. The solution must ultimately be financially feasible for it to serve the institution.

The case for replacement

Several critical conditions can drive the argument for total campus replacement. They include the following:

Aging facility and infrastructure. The campus and facilities are dated and require excessive capital to modernize with marginal potential payback in years of service. Floor-to-floor heights are inadequate for modern ventilation requirements. Column spacing is too tight and inflexible for efficient space planning, particularly with planning of large diagnostic and treatment departments like imaging and surgery. Building systems such as HVAC and power are insufficient to support modern health care spaces with increased air changes and advanced imaging modalities. There is no "domino" space to allow modernization of existing spaces.

No space for expansion. The institution has filled its campus with necessary program clinical components. All sites have been maximized vertically and horizontally with modern structures. No further contiguous real estate is available and every possible unnecessary program has been outsourced or moved off campus. Without more space to grow and modernize, the institution will stagnate.

Adjacencies and zoning are failing. The incremental growth of older institutions often causes inefficiencies in the zoning and adjacencies of various program elements. As elements grow concentrically around key departments, they get more distant from the elements to which they should be adjacent. This strains the key adjacencies and detrimentally effects efficiency and operational costs. When many of the key adjacencies are compromised or departments are fragmented, it might be time to look for a new site.

Opportunity to sell the campus. When another organization sees more value in your location than the current owner does, it could provide the incentive needed to finance a move. This is often the case when a downtown urban campus moves outside a city center, freeing valuable downtown real estate.

Great site available. When a perfect location becomes available that is central to the organization's market, accessible, large and open, without zoning or neighborhood encumbrances and perhaps even donated by a generous board member, it can be an enticing incentive to move. Sometimes real estate adjacent to one of the organization's current neighbors can be traded for better space.

Beneficial financing. Available money is one of the key drivers of master plan decision-making. The current climate of shrunken endowments and increased cost of capital have hampered the availability of money. But in the next 10 years, as the economic cycle swings again, a beneficial economic environment could return.

Supportive donor. Occasionally a donor will fund the majority of the cost

of a project, making the financial barriers to new construction fade. This is a wonderful, low-cost opportunity to start fresh, provided the other factors are in place.

The case for renovation

On the other hand, there are a number of conditions under which upgrading an existing health care campus through renovation and addition is preferable. They include the following:

On the other hand, there are a number of conditions under which upgrading an existing health care campus through renovation and addition is preferable. They include the following:

Good campus condition. Existing campus structures are less than 25 years old with many years of additional life remaining. The campus engineering and technology infrastructure is modern with space and capacity to upgrade. Departmental planning is relatively recent, supporting efficient and cost-effective operations and modern clinical standards.

Space to grow and adapt. If there is room to double the square footage of a campus, either horizontally or vertically, the organization should have many years of comfortable growth available. While health care organizations can never imagine needing more space immediately after completing a new campus, big addition or reconstruction, health care institutions invariably need to change and grow.

Great existing location. Many older academic medical centers have cherished locations in downtown areas surrounded by mutually supportive partner institutions, academic centers and research institutions. In such cases, it makes sense to try to make the current location work for the organization.

Limited alternative sites. Most downtown urban areas have few large sites available to relocate a major medical center campus—typically 15 to 50 acres are required for a major health care institution. The exception to this requirement would be a "vertical" hospital. In most of these situations, the present campus may offer more opportunities than limited sites located elsewhere.

Urgent needs and timeline. Over the past 15 years, the pressure for new and updated clinical facilities often has necessitated fast-track design and construction cycles to get facilities up and operating quickly. This can be driven by competition for markets and patients, closing of neighboring health care facilities or the rush to hit opportune cycles in the construction market, which is currently the case. In such instances, renovations and additions can provide a faster and more efficient way to make smaller scale upgrades to a campus.

Limited capital. Money is the real driver for most renovation or replacement decisions. It takes significant capital to build a new health care campus, replacing everything in a new location. In addition to the bricks and mortar, the hidden elements of utilities infrastructure, roadways, equipment, furnishings and fees significantly add to the replacement cost. Without significant capital, it is nearly impossible to consider replacement.

Making the choice

The choice to replace or renovate is based on many interconnected issues.

It should be made objectively and methodically, uncovering all pros and cons before committing to one path or another. A thorough master planning process should develop diverse alternatives, each with a distinctive approach.

Accurate and comprehensive costing is the key driver in the decision-making process, with the chief financial officer providing the ultimate measurement of both first and long-term affordability.

With these analyses in place, health care organizations can make a thoughtful decision on future growth. hfm

William Mead, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, is a principal of the national health care design firm of Shepley Bulfinch. He can be contacted via his e-mail address at wmead@shepleybulfinch.com. He was assisted by Katherine W. Faulkner, AIA, LEED AP, an associate principal at Shepley Bulfinch.

| Sidebar - When replacing a facility is the right answer |

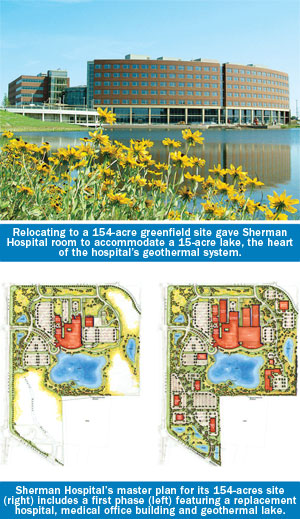

| Sherman Hospital, Elgin, Ill., originally opened in 1888 in a two-story house donated by a local businessman. By 1999, after more than a century of additions, the hospital was pushing the physical limits of its site. Having become a heart center for Chicago's northwest suburbs and a center of excellence for trauma and emergency services, birthing, orthopedic, cancer and diabetes care, the hospital on Center Street was dealing with ongoing issues of congestion and parking shortages. The purchase of a 154-acre greenfield site west of downtown at last gave Sherman Hospital the opportunity to plan for the long term. A 50-year master plan was developed that would give Sherman the capacity to meet the needs of the community for several generations. The first phase of expansion was a $270 million, 645,000-square-foot replacement hospital that opened in December 2009. The planning efficiencies of the project allow it to be slightly smaller than the Center Street campus it is replacing. The new facility includes 255 beds, all of which are private, compared with the existing campus, where only 30 percent of the beds were private. The greenfield site also allowed the hospital to accommodate a large diagnostic and treatment floor plate. Surgery, intensive care units, cardiac beds and the emergency department share the second floor, providing appropriate departmental adjacencies. Radiology, cardiac rehab, physical therapy, women's health and other outpatient services occupy the first floor, together with an array of public functions. The generous dimensions of the site allowed the construction of a 15-acre lake as part of a geothermal system. The geothermal net on the lake's bottom makes Sherman one of the world's most energy-efficient health care facilities, lowering space conditioning costs by 30 to 40 percent, saving the hospital more than $1 million annually. The next steps in developing the campus include an additional medical office building, an added bed tower and supporting services, and community resources for health and eldercare. |

| Sidebar - Making the choice to expand a campus |

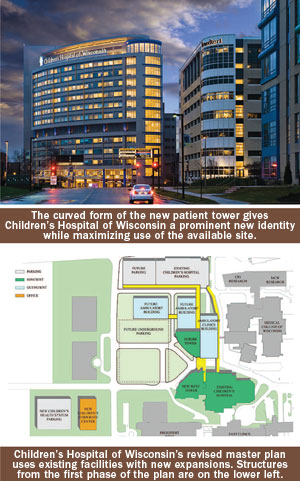

| In 2002, Children's Hospital of Wisconsin (CHW) in Milwaukee was expanding its market share and growing exponentially. While the organization had moved from central Milwaukee to a campus west of the city in 1988, its relatively new campus and 800,000-square-foot patient tower was already reaching capacity. As the organization's clinical success, combined with the increased acuity of its patients and the demand for new technologies, continued to drive the need for more space, the opportunity to purchase a 42-acre site across the street fueled the planning of a replacement hospital. After planning and pricing, however, it proved too expensive and the phasing unworkable. This led the design team to look more closely at optimizing the existing campus and identifying opportunities for the potential doubling of space within the constrictive site limits of its existing campus. The resulting master plan allowed for several future growth directions, one maintaining inpatient and outpatient operations together on one side of 92nd Street and a second option splitting inpatients and outpatients on either side of the street. A plan was adopted that allowed either development to occur over the following two phases: The next step in campus development will be to upgrade the surgical capabilities with more technically advanced cardiac services and interventional medicine. |