At Denver Health, facilities managers and engineers have led the way on many cost-saving projects under the hospital system's lean performance improvement program.

Since 2005, operations staff have slashed average bed turn-around time from 150 minutes to 88. Engineering has saved $550,000 on spare parts and supplies by adopting a bin system and other techniques that reduce hoarding and ensure prompt reorders.

The scrutiny even extends to small items, such as saving unused feeding-tube cans after a patient's discharge. Staff saved the hospital $219,000 over the past year by having asthmatic patients safely share common inhalant canisters.

These are the types of cost-reduction and quality-improvement efforts that will be essential as the far-reaching Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) takes effect in stages over the next several years, say hospital engineers, operations and materials managers, architects and construction managers. And, even if subsequent congressional actions adjust the direction of reform, the momentum for change will not disappear.

To help hospitals succeed under health care reform, experts say managers in these areas increasingly will have to collaborate with senior hospital executives and clinical leaders to make value-based decisions across the hospital environment.

'A wake-up call'

"It's a wake-up call to facilities managers to step out of our traditional role as technical experts and become hospital leaders," says Dale Woodin, CHFM, FASHE, executive director of the American Society for Healthcare Engineering. "This is a huge opportunity for engineers and facilities managers to move beyond technology and construction design to patient care improvement."

The PPACA law includes myriad provisions to expand health coverage, reduce cost growth, improve patient safety and quality of care and expand community-based primary care. Experts say hospital revenues likely will be squeezed, at least until measures to extend coverage to 30-40 million more Americans take effect in 2014. Under the new law, hospitals will be paid less by Medicare if they exceed a certain rate of preventable readmissions within 30 days, and Medicare's payment update factor for hospitals will be reduced. There also are several new initiatives to control costs by bundling payment for episodes of care.

"It puts pressure on the supply chain to fund that loss," says William Stitt, CMRP, FAHRMM, vice president of materials management at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Jersey and president-elect of the Association for Healthcare Resource & Materials Management. "So now we're working collaboratively with clinicians to make good clinical, operational and financial decisions. We need to play in areas where materials managers haven't always played."

That means purchasing decisions increasingly will have to be based on effectiveness and value rather than price alone, on everything from tongue blades to beds to stents to knee implants. "Are we putting in the most appropriate devices for the patients we have?" Stitt asks. Ultimately, treating physicians have to make that decision, he adds, but materials managers need to have a voice in the product-selection process.

Decision-makers likely will have more and better information on the comparative value of different medical devices, drugs and procedures due to a more robust federal comparative-effectiveness research program created by PPACA and the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, also known as the economic stimulus bill.

"Reform is going to make hospitals take a closer look at whether they should pay for new equipment if the evidence isn't there to show greater effectiveness or safety than existing technology," says Jim Keller, vice president for health technology evaluation and safety at ECRI Institute, which reviews the scientific evidence on devices and drugs.

The new Medicare payment policy on preventable readmissions raises the stakes for reducing health care-associated infections (HAIs) and other conditions, and that means new pressure on environmental and operations managers.

Patti Costello, executive director of the Association for the Healthcare Environment, formerly known as the American Society for Healthcare Environmental Services, says managers will have to improve processes to minimize the chances of infection via high-touch surfaces and objects. And they'll have to do it with fewer resources. "We're trying to teach people to standardize processes, eliminate defects and remove inefficiencies without cutting corners on safety and quality," she says.

A team approach

Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle is ahead of the curve in having facilities directors, designers and engineers work with clinicians to reduce HAIs, patient falls and other causes of preventable readmission and longer stays. Interdisciplinary teams have studied how to minimize patient transfers to cut down on falls, and have examined new ventilation techniques and such surface materials as copper to prevent the spread of infections.

"When we look at the causes for readmission, the [hospital's] physical environment is a major source," says Stephen Grose, Virginia Mason's administrative director of support services. "Health reform will require a comprehensive approach to operations and design. I don't think it's a maybe. It's a must."

Hospital architects and construction managers also will have to become more a part of multidisciplinary strategic teams in the post-reform era, says Joseph Sprague, FAIA, FACHA, senior vice president at HKS Architects in Dallas and president of the American College of Healthcare Architects. With millions of newly insured patients, hospital systems must figure out their needs and how best to provide access. Medicare, he notes, will offer incentives to deliver more outpatient care.

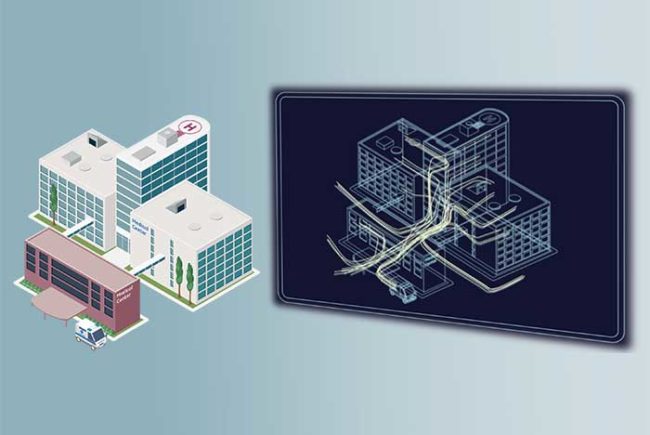

Designers and builders will have to craft smart facilities that reduce the fixed cost of providing care, incorporating energy savings, sustainable materials, and a modern information technology infrastructure, Sprague says. Facilities likely will be more mixed use — including chronic care and long-term care — than just acute care and medical-surgical, due to the health needs of an aging population. He also stresses the need to design for the coordinated flow of patients through the hospital to maximize safety and quality of care.

"The best advice for designers is try to be as flexible as possible and accommodate unforeseen changes in technologies and patient care," Sprague says. "The bottom line is you'll have to become much more knowledgeable about what's going on out there."

The IT connection

Given the new law's emphasis on primary and community-based care, such as the patient-centered medical home, "the $64,000 question for planners and designers is which services will remain on the hospital campus and which will be dispersed throughout the community," Woodin says. This community-care focus also means that hospitals will have to adopt technology to monitor patients with chronic conditions at home remotely, to better prevent hospitalizations.

Hospitals also face a looming timetable under the stimulus bill to implement meaningful use of electronic medical records (EMRs), which is considered integral to health reform. This creates challenges for materials managers, engineers, and designers, as well as information technology (IT) managers.

"It forces us to look at how different systems and medical equipment talk to each other," Stitt says. "We need a long-term plan for IT infrastructure, and when we make medical equipment purchases, we have to be concerned about how that equipment fits into the plan."

Installing EMRs and advanced IT is a particular challenge for older hospitals and those with a mix of older and newer facilities. "We're seeing a huge demand for bedside-driven data," Woodin says. "But the technical challenges in getting the same reporting and data exchange throughout a complex variety of buildings is a problem smacking us in the face now."

The Joint Commission has put out a sentinel-event alert about safe adoption of IT and is working on measuring the meaningful use of EMRs, says Trisha Kurtz, director of federal relations. It also has just released proposed requirements for accreditation of patient-centered medical home programs, and is looking at how to evaluate accountable care organizations.

More broadly in the post-reform environment, the Joint Commission would like its on-site accreditation surveys to be considered in Medicare's ranking of hospitals under its value-based purchasing initiative that ties financial incentives to specified performance objectives. But it's not yet established whether accreditation will be part of that ranking. "You can't measure everything," Kurtz argues. "We believe someone needs to go out and do an on-site assessment visit."

While experts urge a multidisciplinary collaboration among facilities professionals, senior executives and clinicians, a major issue is whether the culture of particular hospital organizations will allow that to happen. "Finding a methodology everyone can agree on to make decisions will be a challenge," Stitt says. "But health reform will make that an absolute necessity. It will become much easier to add to the bottom line through expense reduction and cost avoidance than through generating additional revenue."

Another big question is whether facility managers will focus on the shrinking resources and get discouraged, or embrace the challenge of leading their institutions into a new era of lower costs and better care.

'Let's roll up our sleeves'

"I've heard doom and gloom for the 28 years I've been in health care," Woodin says. "I can't ever remember when they didn't talk about doing more with less. But the rising cost of health care is unsustainable and we can't keep doing what we're doing. Let's roll up our sleeves and get to it."

Harris Meyer, Yakima, Wash., is a freelance writer who specializes in health-care industry topics.