Engineering team's quick thinking keeps Hurricane Harvey damage at bay

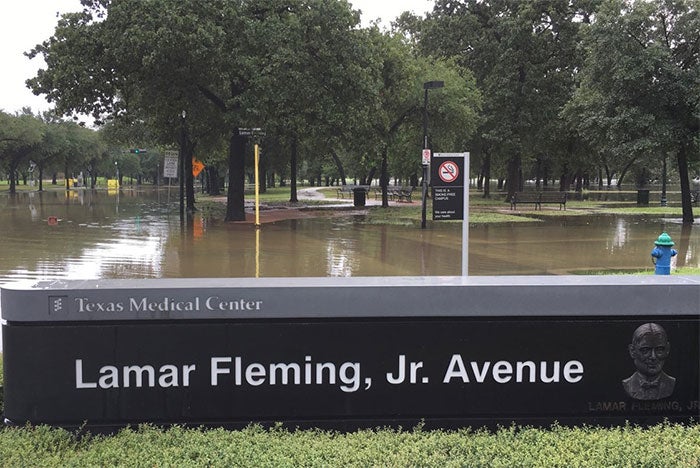

Flooding outside of Ben Taub Hospital's emergency department the day after the pipe bursts.

The engineering staff at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston prepared for Hurricane Harvey in all of the usual ways a hospital gets ready for a storm. For instance, the team sealed up windows and ceilings and used plastic sheeting to funnel rainwater into buckets to mitigate multiple leaks caused by high winds and the heavy rainfall hitting the building at a horizontal angle. But, as more than 26 inches of rain continued to pour down on the city within a 24-hour span, local infrastructure meant to protect Ben Taub Hospital and surrounding facilities started to give way.

The banks of the nearby Brays Bayou river were overrun, sending floodwaters into street drains that were soon overwhelmed. Floodwater began to make its way into the hospital’s plumbing systems, and Ben Taub’s infrastructure was hit hard. A pipe in the basement of its main facility suffered a 30-foot gash, and floodwater began rushing into the facility. Benny Stansbury, director of facility management and engineering, and his 16-member team called on the city for help.

Houston city officials turned on pumping stations to stop or reduce the backflow of water into the hospital. Within 30 minutes, the leak stopped and the crew put up more plastic sheeting around the basement’s walls to funnel any spillage into bins. The engineering team and other support staff placed sandbags in doorways, lifted supplies and equipment to higher ground, and swept water out.

“There’s a lot that goes through your mind at a time like that,” Stansbury says. “But one thing we had in mind was our patients. We knew that if we didn’t get it stopped, we were going to have to evacuate the hospital, and that just doesn’t happen.”

Unfortunately, the hospital’s woes were not over. Five hours after its initial emergency, another pipe burst in the adjacent Ben Taub Tower, where the main hospital’s laboratory, telecommunications and medical records are housed. A cap had blown off a main drain because of the same intense floodwater pressure that caused the first pipe burst. Water in the tower’s mechanical room rose to six feet in some spots. Water came dangerously close to electrical panels and telecom consoles. Any higher and all electricity to the tower and telephone and computer services for the entire hospital could have been cut off.

Engineering staff work to clear out floodwaters from Ben Taub Tower.

“At one point, we didn’t know if we were going to be able to save the hospital,” Stansbury says. “Guys were all tired and wet. They were lined up against the wall and looked like they had gotten beat up. One guy said, ‘We can’t stop it. What are we going to do?’ I said, ‘You know, there’s a lot of experience in this room. You stop and think for a minute. Someone has to have some ideas.’”

They did. Soon, the engineering team was rigging pumps and clamping the broken pipe. One engineer waded through the water on hands and knees to find the blown-off cap, secure the pipe and begin clearing the water. The crew drilled holes into walls to allow water to escape into the building's water retention pits. At one point during this process, the staff set up an assembly line to hold the electric hammer drill’s cord above the water and prevent electrocution.

The engineering team’s quick thinking paid off, and the hospital only had to evacuate a few patients during the storm. Stansbury says the hospital is using the event as a learning experience and implementing multiple measures to prevent future damage. For instance, valves have been installed on all drainage pipes leaving the building to ensure that if outside water backs up causing pipe failure the engineering team can stop the flow until repairs can be made.

Another issue the engineering team faced during the flooding was the amount of time it took to sweep water out of the basement. "Due to the amount of halls and walls we could not get the water down or out in an efficient manner," Stansbury explains. "Holes have been cored through select walls to redirect flood waters to sump pumps in the slim chance this would ever happen again. Valves and aesthetically pleasing decor have been placed on these holes to keep covered until needed."

Also, pump motors and transformers were raised several feet to prevent them from going under water again. The hospital is in the midst of conducting a feasibility study to assess the benefits of either placing a suitable retaining wall around the remaining electrical and telecommunications equipment or raising it to a suitable height.

Stansbury says the team's quick thinking prevented systems from shutting down and from the hospital having to evacuate many patients. “We didn’t know we were going to be superengineers,” Stansbury says. “It was a combined effort of everybody.”