Initiative takes aim at reducing hospital violence

The St. Barnabas Innovation 90 violence-reduction task force includes (from left) Morena Lasso, James Andino, Daniel G. Murphy, Halana Finnie and La Shemah Williams.

Image courtesy of St. Barnabas Hospital

Violent behavior is always a risk in a big-city medical center, particularly in the emergency department (ED), the bustling point of intake. St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, part of the SBH Health System, made a conscious choice to address these incidents head on.

Since summer 2017, in response to a shooting at a local hospital, SBH has become more engaged in curbing violent events. In general, EDs throughout the Bronx have been experiencing an increase in violent incidents involving patient-to-patient and patient-to-staff assaults. The consensus is that nurse retention and staff morale have suffered, with anxiety and absenteeism on the rise.

SBH recognized the seriousness of this escalation and its negative impact. As a result, it made a commitment to address this concern proactively.

Violence-reduction task force

SBH administrators assembled a multidisciplinary task force to investigate the problem and develop solutions designed to reduce violence in the ED and increase staff and patient safety.

The task force consists of five key members: Daniel G. Murphy, M.D., MBA, chairman, department of emergency medicine; Halana Finnie, Ph.D, R.N., PMHNP, director of nursing, behavioral health and addiction services; Morena Lasso, CPSO, CHSP, CHEP, safety officer; James Andino, associate director of security; and La Shemah Williams, LCSW-R, administrative director, SBH Health System Behavioral Health.

A closer look at SBAR elements

Situation

- Asking/learning about the patient’s situation and providing a brief statement of the problem.

Background

- Providing important clinical context and concise information related to the situation.

Assessment

- Stating what you think the problem is and/or what you found.

Recommendation

- Stating what you recommend or want.

Their first mission was to attend an Innovation 90 boot camp provided by the American Hospital Association last November at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

Described as a methodology that’s been proven to solve tough problems experienced by many health care organizations, Innovation 90 espouses a design-thinking process that’s both imaginative and analytical — one that enables cross-functional teams of as many as five people to have a major effect on patient outcomes and hospital operations in as quickly as 90 days.

At the boot camp, the task force was guided to define its challenge and make hypotheses, analyze data, explore solutions and outline a project plan.

Once back at the hospital, a three-month, rapid-prototyping phase began (which, for the St. Barnabas team, meant three, 30-day sprints). At this stage, an estimated 10 hours per week were spent improving on the planned solution; daily 15-minute “scrum” calls and weekly meetings were held with key stakeholders, clinical contacts and subject matter experts. Additionally, tasks were assigned, research was conducted, front-line employees were interviewed, data were gathered and evaluated, the process was reviewed and a solution proposal was completed.

“We started by immersing ourselves in the emergency department,” says Finnie. “We experienced firsthand what happens from the point of entry through the triage process — observing how patients are cared for and where staff are located. We questioned staff about their personal experiences dealing with these ED patients. And we closely examined the data.”

Lastly, a presentation was made to senior leaders, resulting in favorable reviews. The three solutions that were proposed by the task force included:

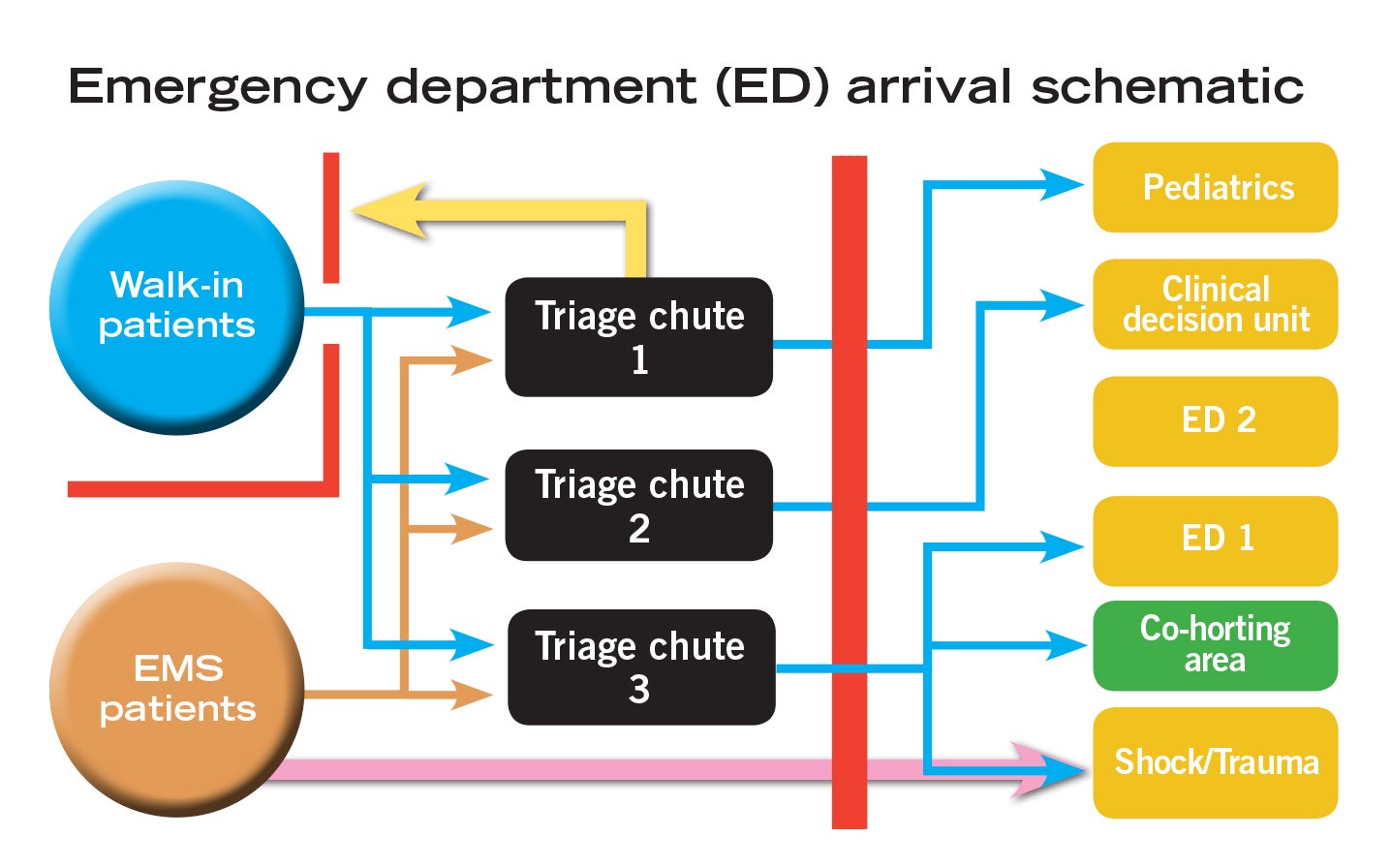

- Triage relocation — physically and functionally redesigning the ED’s triage area to better control access to the environment of care and improve triage efficiency.

- Cohorting of intoxicated, behavioral and/or homeless (IBH) patients — standardizing the assessment and treatment of these high-risk patients.

- Program management — educating and training employees on the use of verbal de-escalation techniques and the SBAR [situation, background, assessment, recommendation] communication tool; rolling out new policies and procedures to enhance workflow and efficiencies; and using quality metrics.

Fixing the bottleneck

The team came to its first solution, triage relocation, after identifying a major culprit: the ED’s current ambulance triage area and several geographical, architectural and structural issues that needed to be addressed.

“This area is located right in the midst of our midtrack zone — a medium acuity area devoted mostly to ambulatory patients,” says Murphy. “Ambulance triage is located in a space not ideally suited to handle the increased volume, creating an uncontrollable access portal for the general public.”

The anticipated benefits of triage relocation include more controlled and secure patient access via the waiting room as well as an improved environment of care and patient experience in the ED.

Consider that the hospital’s influx of IBH patients has been steadily rising in recent years as a result of the hospital’s having standardized its intake process for these patients. The unintended consequence of this more efficient system has been that the city police and emergency medical services (EMS) departments have been delivering more IBH patients to St. Barnabas.

“These are patients who are being admitted to various units within the hospital, which not only impacts our emergency department, but also other inpatient units once they are triaged and admitted,” Finnie says. “So it’s a hospitalwide concern, not just an ED issue.”

Murphy notes that triage relocation will not involve an outward expansion or adding new square footage; instead, interior walls will be moved and existing areas reshaped to improve patient flow and safety. “This will allow us to combine both ambulatory triage and ambulance triage,” adds Murphy.

Among the advantages of merging triage functions are enhanced staff presence (in the form of three nurses and two technicians who can simultaneously triage walk-in and ambulatory-transported patients); improved satisfaction among EMS workers; and revised procedures like parallel processing, designed to decrease EMS turnaround time.

“Today, the average turnaround time from when an ambulance arrives to when it leaves for the next job is 37 minutes, up from about 30 minutes a decade ago,” Murphy says.

Cohorting and program management

The second proposed solution, cohorting, involves designating a specific area for IBH patients within the ED. Once triaged, they can be safely separated from the mainstream ED population and placed in this new area, which would be managed by specially trained staff.

The plusses of cohorting are multiple. It creates standardized, protocol-driven care that’s safer for staff to administer. It promotes more efficient collaboration and clinical decision-making between psychiatry and emergency medicine. Furthermore, it enhances the patient experience and the environment of care in the ED.

The third proposed solution, program management, is equally significant.

“It entails looking closely at and improving ED policies and practices. This includes the way patients are evaluated and triaged, staff workflow and patient throughput — from the ED to an inpatient admission to being discharged back into the community,” Finnie explains.

Additionally, it calls for teaching verbal de-escalation, patient debriefing and post-incident care techniques to staff throughout the hospital, “who will need these skills to recognize and safely intervene when a patient is becoming anxious, defensive or physically aggressive,” says Finnie.

Evaluating recommendations

Innovation 90 promotes an objective of recommending solutions by the end of the 13-week prototyping phase. The task force was successful in meeting this objective. St. Barnabas leaders will evaluate each of the three recommended solutions separately. Triage redesign will be considered first, followed by the proposed cohorting area. Elements of the program management solution already have been developed and will start with an expanded workplace-violence education and training program involving new and existing employees.

“Staff need to feel comfortable and confident when confronting challenging situations. Knowing how to recognize changes in mood, affect [emotion], behavior or communication will allow staff to respond proactively, not reactively,” says Finnie. “It also gives staff time to put additional resources in place before a tenuous situation escalates into something more aggressive. We will continue to ask staff for feedback regarding its effectiveness and analyze data to see how these strategies impact our safety and quality metrics.”

Program perks

Finnie says Innovation 90’s unique approach to problem-solving helped the task force save time, form the right conclusions and propose the best solutions.

“Their systematic and methodical approach is very different from the traditional project management model that typically looks at what exists and then tries to tweak it with minor improvements and feature enhancements,” says Finnie. “Innovation 90, by contrast, asks you to think outside the box and explore new and different techniques that you’ve never tried before. It challenges you to look at the same problem, but with fresh eyes, as a small group and come up with different perspectives.”

Lasso echoes that sentiment. “The consistency of talking about problems and solutions during our daily scrums and weekly meetings made a big difference,” says Lasso. “And being coached along the way by Innovation 90 experts really helped, too. Our security staff are now using different approaches we learned in the program.”

Murphy was impressed with the hundreds of ideas the group was able to brainstorm during the three-day boot camp, a period that fostered both critical and creative thinking. “Soon, we were able to narrow it down to the best three solutions.”

Proposed outcomes of these implemented solutions include a safer work environment where verbal and physical threats, violent acts and events, and staff injuries are reduced while patient satisfaction, staff recruitment and retention, and quality metrics are increased.

The return on investment would also come in the form of decreased costs spent on workers’ compensation and disability claims, risk management and medical/malpractice lawsuits, treatment for falls, recruitment and training, sick calls, overtime and agency expenses.

What happens next?

Andino cautions, however, that there’s still a lot to learn, and their plans may need to be revised along the way.

“We won’t know, for example, if we need more security in the emergency department until the redesign is done,” he says. “But once we streamline our processes and properly train staff to be aware of what their duties are, we’re confident that violence in the emergency department will be minimized. And that will make for a safer workplace.”

While it’s still premature to come to a verdict on the multidisciplinary task force’s plan or measure its effectiveness, Finnie hopes that other health care organizations can take the lessons learned by St. Barnabas to heart.

“Workplace violence is a serious problem that you cannot ignore. In tackling it, you can’t be afraid to embrace change, explore new ideas and try something different,” according to Finnie, who adds that it’s crucial to get input and buy-in from affected staff about your suggestions.

“Worst-case scenario? If it doesn’t work, you try something else,” she adds.

Erik J. Martin is a freelance writer based in Oak Lawn, Ill.

Health facility professionals can find more information by visiting the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s website at www.ihi.org.