Making connections

New health care delivery models and federal mandates for meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) are creating demand for increased communication, information sharing, access to patient EHRs, complex interfaces and interoperability across multiple platforms.

New health care delivery models and federal mandates for meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) are creating demand for increased communication, information sharing, access to patient EHRs, complex interfaces and interoperability across multiple platforms.

Carefully weighing these considerations and navigating the numerous variables that exist in a modern medical equipment integration project are essential for improving clinical efficiency without negatively affecting the environment of care.

Need for interfaces

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) section of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 provided a financial carrot-and-stick approach to increasing the use of EHRs. The strategy has worked, but there is still much to be done. According to the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), only 14 percent of hospitals have achieved 2013's goal of Stage 5 meaningful use.

As clinicians begin to utilize integration such as computerized provider order entry, clinical decision support and error checking, they expect even more integration of other devices and systems. Clinicians want integration that generates notifications of potential issues with protocol reminders and alarms. They expect the EHRs to be populated from wireless device interfaces with beds, ventilators, physiological monitors, IV pumps and other equipment to save charting time and increase accuracy.

Medical device manufacturers are responding with new or enhanced equipment and devices capable of integrating with the EHR. The integration required to support these functions impacts workflow, requiring process evaluations that change infrastructure and integration needs.

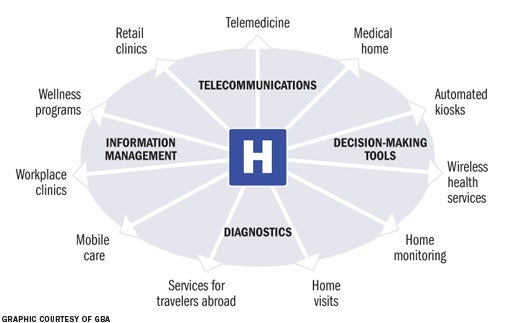

Another influence is the accountable care organization (ACO) model. The ACO model and the associated Medicare Shared Savings Program create new equipment, device and systems integration requirements, including remote monitoring of clinics as well as supporting critical access hospitals within midsize and large ACOs. The model also supports more home monitoring of patients with chronic conditions, which substantially expands a facility's requirements for telemedicine, remote medical device monitoring and associated interoperabilities. Integration to enable remote diagnostics and physician call centers also may be needed.

Finally, Medicare reimbursements will be based on performance, rather than services, creating the potential for greater financial risk. To counteract this risk, facilities are looking for ways to increase efficiencies through Lean health care methodologies, and medical equipment integration can help support Lean processes.

Interoperability challenges

Before health facilities professionals start down the integration and interoperability road, they should be aware of the bumps and turns that may occur along the way. Some typical interoperability challenges include the following:

IT infrastructure. Many vendors assume that facilities have the needed infrastructure to support their equipment and integration, or they think they can work out the details during the implementation stage. However, the requirements for space, power, redundancy, cabling, wireless infrastructure and responsibilities for installation can vary greatly between manufacturers and options selected. Whether the installation is occurring in an existing facility or a new facility adds another level of complexity.

If the manufacturer requires a dedicated gateway server located in a department's telecommunications equipment room or the hospital's main communications room or data center, for example, the project team must be sure there is sufficient rack space available or room for another rack. Likewise, some manufacturers utilize standard cabling but some require proprietary cabling. If they are using the hospital's existing network infrastructure, the project team must decide what that impacts and who needs to approve the installation. If proprietary cabling must be run in an installation in an existing facility, the project team must determine the impact.

Bandwidth issues. Many facilities overlook the bandwidth issues created by multiple devices placed on a typically overburdened existing wireless infrastructure. This situation often results in a medical device manufacturer being called to a facility post-installation to address presumed equipment problems, only to learn the infrastructure is inadequate. Finger pointing quickly ensues, ultimately resulting in discussions on how quickly the added network gear, access points and associated cabling can be installed for the system to function correctly. Not understanding that an equipment manufacturer's wireless option requires a $15,000 server implementation and $20,000 electronic health record interface can quickly overrun project contingencies.

Overlapping functionality. In the past, nurse call systems were not much more than a bell and a light. Now, nurse call systems provide advanced workflow solutions that can integrate with multiple systems and devices. But one of the biggest medical device and nurse call system integration challenges is nomenclature and a refined integration work plan that defines all details from all parties.

For example, the clinicians may explain that they want the bed or pump to notify the nurse of the device alarm and the nurse call vendor may interpret this requirement as a request to pick up this notification on the nurse call system from its auxiliary jack connection. However, the medical device manufacturer may hear that he should provide a data connection and software solution that can send notification to a PC at the nurses' station and the wireless phone vendor may translate the user's request as the go-ahead to provide middleware integration, with the medical device output to display alerts directly to the assigned nurse's phone. Finally, the purchasing department will receive approval from facilities, telecom and biomed to proceed at different times for each of these different solutions. In this scenario, each individual proceeds with good intentions, but together they end up planning, procuring and sometimes implementing duplicate solutions that don't necessarily meet the clinician's need.

Inadequate security. Network security requirements for medical equipment often are forgotten in most projects and can put a health care facility at risk for Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act violations, patient data loss and an exposed network. In the past, many systems were department-centric — each department used its own information system, often from different vendors. Medical devices that were shared or moved between departments did not collect or pass data. The clinicians used paper charts, not a tablet computer. The network could be segregated and data were only shared within departments, so securing data may have been easier. Now the requirements are different and securing data are more complex.

Planning omissions. Health care organizations long have understood the value of master planning for land utilization, building renovations and expansions, and mechanical-electrical-plumbing upgrades, but health care technology often is overlooked or excluded from master planning. Medical equipment, information technology (IT) and associated interfaces can make up 30 percent of a project budget, and have the potential to ruin staff efficiencies or even halt projects if not addressed early in planning. Medical equipment interoperability plays a critical role in project master planning to meet administrative goals and clinical expectations.

Developing a roadmap

The National Institute of Standards and Technology, Health Level Seven International (HL7), Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise and HIMSS are industry standardization champions trying to address the complexities of medical device integration. These groups provide great methodologies and standards, but they are just the beginning of real interoperability requirements. The medical equipment manufacturers are trying to develop plug-and-play solutions, but current standards only provide a starting point to address integration and not final solutions.

Integration may take months to plan and implement. Navigating multifaceted installation and testing hurdles requires regular health care technology coordination meetings that include the contractor, vendors, facilities and biomedical departments, and IT. These meetings must establish realistic critical path timelines and reiterate all team members' roles and responsibilities.

System configuration work sessions also should be included in the integration implementation plan. These sessions include technicians and clinical users working to detail specific system configurations that avoid nursing alarm fatigue and provide Lean health care solutions. To provide complete medical equipment interoperability, the following areas must be addressed:

Physical connectivity. The project team must address the cabling infrastructure; mechanical, electrical and communications rooms; and data center requirements. Assuming medical equipment and IT vendors understand infrastructure issues can create painful implementation surprises. Instead, detailed infrastructure planning is necessary to address both new and existing facilities.

When reviewing a vendor's potential integration options, health facilities professionals should be sure to ask for site prep guides or at least written documentation that defines minimum infrastructure requirements. Assessing these requirements with the impacted internal and external team members helps to avoid budget busts and significant installation delays. Supply chain professionals, facilities and biomedical engineers, and IT should be engaged to ensure that required device options and infrastructure requirements are understood and properly selected.

The ACO model requires hospital leadership to think beyond the hospital. As technology expands into the community, previously independent clinics and other facilities now will be connected to the main hospital and to each other. Yet many of these facilities have insufficient infrastructure or lack reliable power, which has the potential to impact the ACO's mission-critical operations.

Logical connectivity. The team must address network demands for wired, wireless, segregated, redundant and virtual private network operations. Selecting the wireless option when procuring a device may seem to resolve all infrastructure woes, but it can create huge problems in other areas. When implemented correctly, wireless options can provide a flexible solution that can easily relocate and expand without added cabling requirements. Defining the medical devices wireless standard is only the beginning. Engaging the device manufacturer's installation team, as opposed to the sales representative, with the hospital's IT group is critical to avoid potential failure.

Segregation of networks can be utilized to separate traffic on existing infrastructure to enhance security or performance. Especially suitable for processing critical patient data, networks that should be considered for segregation are video, patient monitoring and telemetry systems, or other systems that require large amounts of bandwidth.

Redundancy also is a critical component of logical connectivity. Technology master planning should consider redundancy to help ensure that the network will sustain scheduled or unscheduled downtime and to help protect health care information that relies on continuous connectivity.

Data sharing. This is the mechanism for sending or exchanging data between disparate systems and devices. Data sharing must address data exchange standards such as HL7 and Dicom with defined data mappings, as different vendors may store the same piece of data in a different part of the standard. In addition, smart patient beds typically require special local servers and overlap with nurse-call workflow features; ventilators may require separate data collection gateway devices at each bedside headwall; portable physiological monitors may require barcoding and potential middleware to provide positive patient identification verification; and smart IV pumps may need wireless infrastructure to address closed-loop medication administration requirements. All of these integrations are unique and require a complex work plan that must be implemented from the onset of the project.

Security. Minimum medical device security standards must be required. Issuing internal network security standards as part of the request for proposal and purchasing order requirements will limit these issues. If the facility hasn't established network device standards, the Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security, developed by HIMSS and the National Electrical Manufacturers Association, should provide all parties a good start in establishing project requirements.

Operational requirements. These must be fully addressed to meet real clinical needs. Integration and full interoperability can be a huge, expensive disappointment if the end solution doesn't align with the clinical expectations and meaningful use requirements. It is essential to define the different types of information that will be generated, where that information originates and where the information will be used. It is also necessary to identify the users of the information, where they might be located and the devices they will use to access information.

Post-implementation issues. All complex systems and integration need fine tuning. Establishing a post-implementation work session will provide a forum for clinicians to address interoperability challenges. The project team then can refine the solution that fits operational needs. Likewise, establishing a detailed commissioning process for integration may be required to ensure what the user defined and the facility purchased is truly what was implemented. This will help to ensure that technology is properly utilized and the system is correctly configured.

Finally, training on the new medical device integration is critical to overall project success. Facilities must define training requirements beyond the generic options submitted by vendors. A minimum of two series of training sessions with clinicians and "superusers" should be required, with at least one of these at the point of use.

Defining the vision

The biggest mistake many health care facilities make in medical device integration is underestimating the real impact of medical device interoperability. Defining the team vision early and establishing clear roles and responsibilities are critical to assessing the budget, planning and infrastructure needs. A detailed system configuration plan built with the input of all stakeholders is necessary for success.

Ted Hood is senior vice president and COO at GBA, a health care technology consulting firm based in Franklin, Tenn. He can be reached at ted.hood@gbainc.com.

| Sidebar - Avoiding medical technology overload |

| The promise of interoperability can sometimes lead to technology for technology's sake, rather than the appropriate balance. This not only can lead to unnecessary expense, but can be a detriment to clinical staff and patients as well. A design team can project an attractive scenario in which a smart bed will alert nursing staff when it's time to turn a patient over or sound an alarm and call the nurses' station when the patient tries to get out of bed; nurses will be called on their mobile phone when respirations for another patient fall below a certain level; and a light will go off in the hallway when an infusion is finished on yet another patient, replacing an annoying infusion pump beep that scares patients. However, this attractive scenario soon can turn into a nightmare of similar sounding beeps and rings going off and a confusing array of infusion alarm lights, call lights and transport lights that makes it difficult for the nursing staff to sort out which alarms really need attention and which ones can wait. Between 2005 and 2008 there were 566 alarm-related deaths in the United States, according to the Food and Drug Administration Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database. And the ECRI Institute, Plymouth Meeting, Pa., rated medical device alarm fatigue as the No. 1 technology hazard of 2012. Many device manufacturers now have added the ability to trigger protocol reminders, notifications and alarms into their equipment. Manufacturers are trying to provide the full range of functionality, but many of the capabilities overlap or may even conflict. Without a plan and coordination between disparate vendors and users, and without proper configurations and testing, the results can range from annoying to deadly. By Jolene Lyons, R.N., project manager at GBA, Franklin, Tenn. |