Planning for smart hospitals

Technology is embedded in devices now more than ever, and a smart approach gets the right data to the right entity at the right time for better patient outcomes.

Image by Getty Images

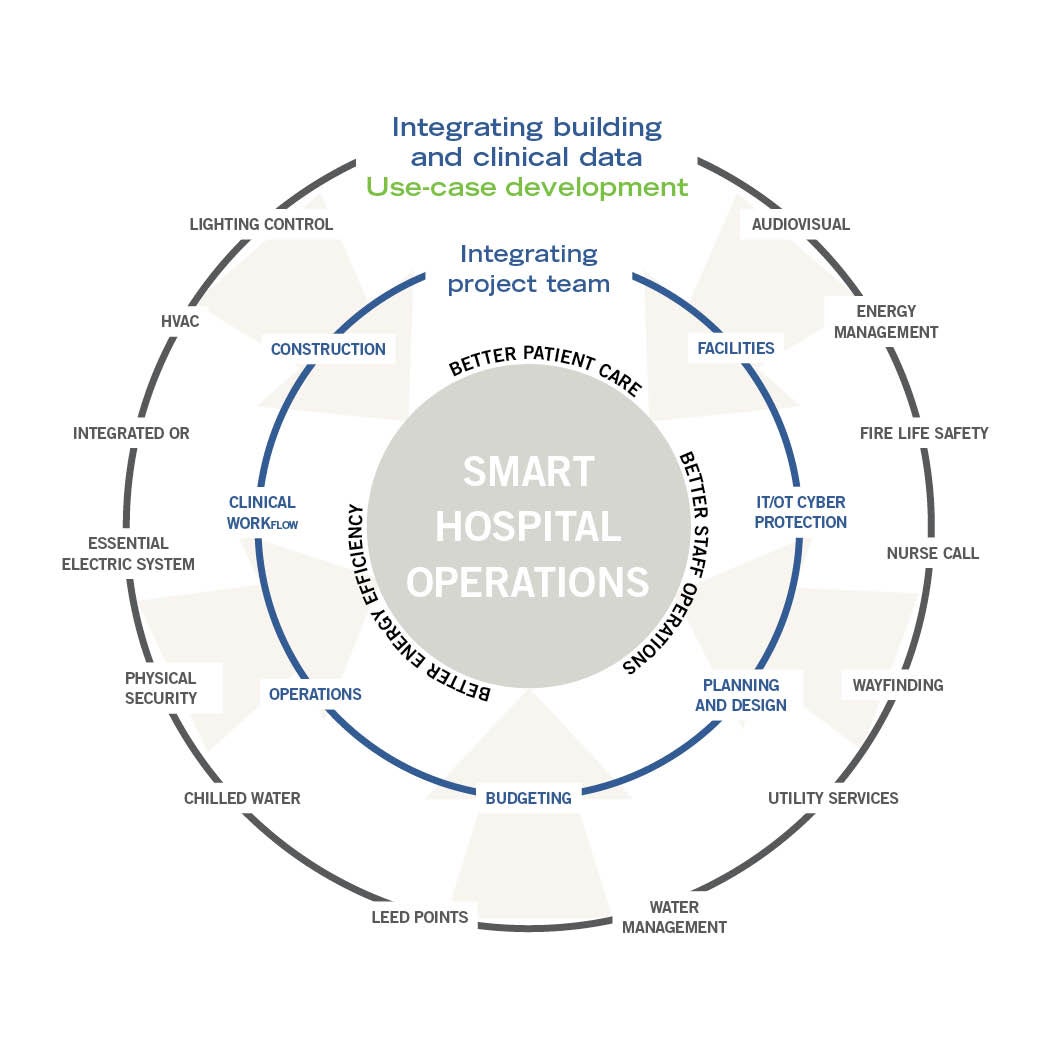

Smart hospitals are built upon the foundation of an energy-efficient, code-compliant and resiliently designed infrastructure by connecting technology to support people through better processes.

They don’t just happen, they are designed. Technology is embedded in devices now more than ever, and a smart approach gets the right data to the right entity at the right time for better patient outcomes, a safer environment and to meet carbon goals.

A smart hospital crosses many boundaries within health care and will directly or indirectly affect most disciplines on a project design team. A few examples where architecture, engineering and hospital operations are affected by a smart hospital design include the following:

- Virtual reality training for clinicians requires a significant amount of architectural programming space training, observation and technology to support the mission.

- Monitoring-based commissioning includes a smart building sensor infrastructure system and software to clearly identify when a system is operating outside of set parameters, pinpoint the problem area and alert hospital personnel suggesting a path forward. Such monitoring-based commissioning is typically associated with an upgraded or smart mechanical building automation system (BAS) design. Additionally, in a smart building environment, the concept can be extended to include other building systems, including electrical power metering, and lighting design and control elements.

- Utilizing robots to transport materials, disinfect rooms or complete nursing functions are operational changes within health care facilities. Leveraging a sensor-based infrastructure that supports clinical and building systems provides both upfront cost and the operational benefits that come from standardization.

Leading with connected technology is a key concept of a smart hospital.

Starting with a vision

Smart hospitals start with a health care organization’s vision, the commitment to a process where technology is considered on the front end, and a challenge to the stakeholders and leaders to fulfill the vision.

A visioning session will kick-start the process, with a requirement for each core team member to have a deep knowledge of their field of expertise, an openness to ideas and acceptance to be challenged. The facilitator for the integration visioning session works with clinician and staff leadership and focus groups to communicate a desired future state. This vision determines desired outcomes and the business case of why data is being shared.

The development of outcomes is where the project team rolls up their sleeves to risk-assess which technology can be applied to best meet the needs of the vision outcomes and how the work is represented by each party in the project process to be accomplished. Identifying outcomes supporting the vision provides the boundaries to achieve smart hospital success on a project. For example, one element of the vision may be “safety and connectivity in the patient room”; the team will need to make decisions for numerous possible outcomes, including:

- Patient and staff capability to view content based on security settings from patient systems, including electronic health records, radiology, cafeteria ordering, education, and entertainment and gaming; content from building systems, including room lighting control, temperature control and shade control; and content from medical systems, including nurse call and bed control.

- Wireless (or nontethered) devices to be used as the main patient interface, coordinated with information technology (IT) and patient billing to recover cost.

- Nonrecording closed-circuit television monitoring stations.

- Medical equipment reporting, protective siderails and remote alarming for patient safety.

- Architectural coordination of a right-sized main display, digital whiteboard and auxiliary corridor patient update display.

These outcomes will require the imagination of most team members on the project, including IT, clinical, architectural, engineering, medical equipment and technology designers. They must evaluate risks for each scenario, consider the expected next generation of technology, and determine the most user-friendly and sustainable way to integrate data to support these outcomes.

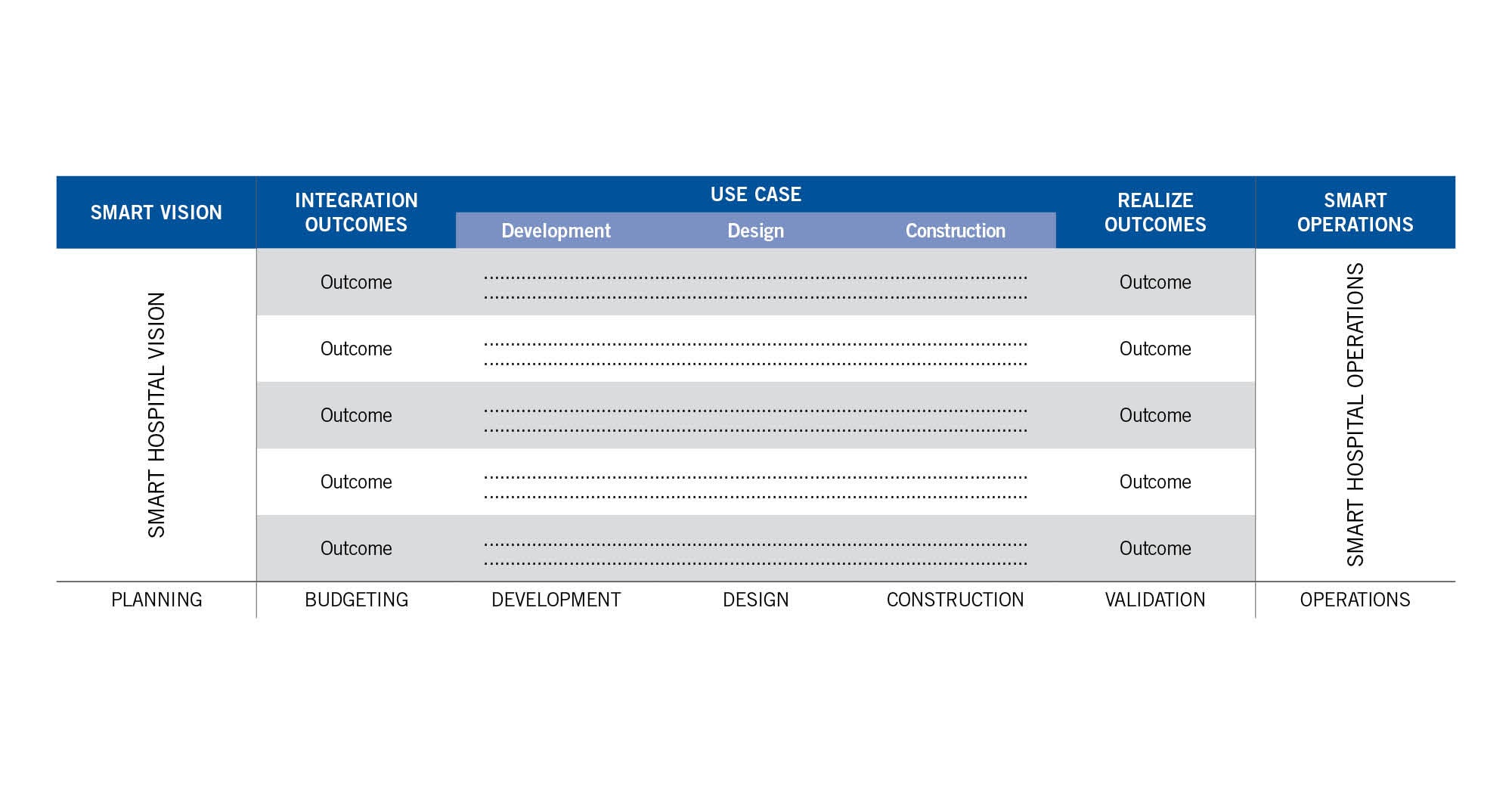

After outcomes are associated with the vision, the next step is to break down each outcome into use cases. Use cases, which span across the owner departments, design team disciplines and contractor specialties, will reflect the team decision on the best long-term way to accomplish this outcome. Commonly, standardization of technology and equipment may be considered for the benefit of software updates, maintenance and cyber protection.

Use-case framework

Use cases are the building blocks of each integration or outcome. Upon the design, construction and commissioning of each use case, each outcome and resulting technology vision is achieved. Use cases are the basis for designing the network data-sharing requirements to be coordinated between the electrical, mechanical and low-voltage engineers, and facilities, clinical and IT teams.

This framework is an important first step that guides interactions between the design team and owner during project delivery and provides a long-term map for building cybersecurity, sustainability and resilience, and deployment of new technology and software updates. Inherent to smart hospitals is the sharing of data within and between building and clinical systems, and the role of the integration project team is to confirm all gaps are addressed.

Outcomes and macro-use cases are best determined prior to design, while the micro-use cases may be developed throughout the project design cycle. Clearly representing use cases in the project documents will allow the contractor to most accurately bid the project.

The mechanical engineering and mechanical contracting fields have extensive history and experience in writing, programming and commissioning sequences of operations, which keep buildings comfortable and running efficiently. Because digital signals are communicated across a network, these building control sequences may be classified as a set of use cases in that network data is shared to achieve an outcome.

In addition, because the BAS computer screen has become the facility dashboard continuously monitored by facility personnel, today’s BAS commonly accepts points from other systems (e.g., generator running) to alert the building operator. Each of these interconnections integrates the data from different systems and is considered a use case. While a traditional mechanical building control sequence will typically stay within the known confines of mechanical specification sections (e.g., BAS, chiller, air-handling unit and pumps), a use case can span across mechanical, electrical, clinical and other systems.

Building controls or a mechanical sequence of operation are considered outcomes or use cases dependent on the granularity.

Smart hospital resiliency

Granular use cases are directly related to the resiliency of the integration, in lieu of letting the contractor determine how to accomplish an integration. One example is a common integration that leverages technology between the BAS and lighting to share an occupancy sensor for the use of lighting control and HVAC setback in an office or conference room. This use case may be realistically implemented in numerous ways:

- The occupancy sensor may include an auxiliary contact for a direct connection to both the lighting control and HVAC control system.

- The room occupancy data may be captured by the lighting control system and communicated to the HVAC control system.

- The room occupancy data may be captured by the HVAC control system and communicated to the lighting control system.

- The lighting control system may be integral to the HVAC control system (i.e., made by the same manufacturer).

Which of these options is the best solution for hospital operations? If this simple and common integration can be completed in at least four different ways, imagine the number of variables associated with a more complex outcome such as the intelligent patient room. The use-case team, with representatives from all members of the project team, can determine the best and most resilient way to accomplish all project integrations and confirm it is represented in the contract documents clearly.

System cyber protection

Technology is embedded in electrical and mechanical devices and, simply put, “if it can be programmed, it can be hacked.” Cyber protection of health care electrical and mechanical systems protects the smart equipment data and services the equipment itself.

Electrical and mechanical systems may be referred to as operational technology (OT), and the cyber protection of this real-world operating equipment is referred to as cyber-physical. Cyber protection has been designed into generations of IT devices, although it is a relatively new discussion for OT. The cyber protection engineer will implement processes and technology differently on IT versus OT, legacy OT systems, or if the OT system provides life safety functions.

It is crucial the cyber protection engineer is engaged in use-case development because their input may drive construction project decisions. During facilities operations, cyber maintenance is critical to maintain cyber protection, and leadership and coordination is essential to schedule and notify health care staff of any resultant outages to their equipment based on the update requirements.

Covering all bases

Reviewing the technology budget during the macro use-case planning session provides an opportunity to validate all scope gaps are covered or that the scope is stitched together. Scope stitching is a conscious effort to look across the building system silos and identify the benefits of data sharing. Rallying around the macro-use cases provides the team with a different view of the technology budget by evaluating and validating its content.

It is a given that technology will change between the project conceptual phase and substantial completion. To limit the impact to project budget and construction, it is imperative that each member of the project team understands the next generation of development within their area of expertise and how it relates to current decision-making.

Technology systems such as those for audiovisual are ubiquitous in health care today and influence areas including conference rooms and education spaces; the board room and auditorium; patient entertainment and interface; telemedicine; and providing a personal welcome to the public. Other areas to ensure are covered in the project technology budget include signage and wayfinding; the intelligent operating room; robotics; people and equipment locating; virtual reality training; and more.

Whenever systems affect physical architecture layouts, or have infrastructure support requirements and IT interfaces, they must be introduced early to drive design parameters. Leading with technology changes, the traditional project process, and introducing specialty team members during the concept and design phase will likely achieve positive results.

Smart hospitals require technology and integration leadership on each project — from the conceptual integration goals to budgeting — and the design and construction actualization of smart hospital elements.

Team comfort zones

It takes a team of knowledgeable professionals to build a hospital. Additionally, smart hospitals require disparate professionals to work outside of their comfort zones.

A four-year time frame from conceptual design to construction of a large project is common for the architecture and engineering field and may be foreign to a health care organization that commonly works with ongoing clinical and IT activities and projects, and coordinates third-party IT providers.

Accepting, and not being paralyzed by, the fact that it is very likely that at least one technology generation change will take place between the proposed design and final product delivery, and understanding how this will influence the project construction and schedule, is required to clearly share these risk elements with the project team.

Leading with technology takes time — especially for coordination at every project phase — and dedicated team member resources need to stay on top of a smart hospital initiative.

Clearly representing all use cases to all parties is paramount to the development of a smart hospital. Each team member knows best how concepts are communicated in their field of knowledge and what processes need to be in place to ensure a successful go-live on a use case or outcome, and resulted vision.

Leading with technology may require a different way to think about how contracts are awarded. Too often the BAS contractor is assumed to be the integrator and, while it’s true that the majority of use cases in today’s buildings are mechanical in nature, this arrangement may leave the BAS contractor with limited or no authority to execute nonmechanical (e.g., electrical and lighting) integrations.

One solution is an independent integration platform or “single pane of glass” that sits above the BAS and is a single source for all OT data and a common visual platform. This single source may be more manageable for software and firmware updates and sharing building data for clinical and IT-intensive use cases.

Milestones during construction can discipline all parties to proactively complete the work necessary for integration and may not be found in the typical construction schedule. Leading with technology is only as good as the work is executed, and following a process from design to bid to commissioning is required to stay on top of this initiative, validating the importance of the smart hospital vision.

Leading with technology requires an additional step for the smart hospital project team to integrate building systems with clinical IT and clinical operations. Once the project team is comfortable communicating across these traditional silos, a waterfall of opportunities is released.

Gathering the right integration team

Similar to gathering the right talent to take part in the smart hospital visioning session, having a core team of integrators to lead the smart hospital implementation is necessary for success. A smart hospital leadership team includes representation from ownership, engineering, clinical and information technology, design and contractor groups.

It takes a team of integrators to validate that the vision is properly scoped and assigned within the project team, and where specialty integrators may be required. The integrator team confirms all gaps are closed and leads their respective teams from a technology integration perspective.

In addition to thoroughly understanding integration methods in their technical space, each integrator team member needs to have 360-degree vision and willingness to understand technology outside of their fields of knowledge to properly and completely risk-assess each integration solution from a design, construction and operations perspective.

After the design scope for each integration vision or outcome is determined, the process continues with generating breakdown packages for each outcome to a level where each can be proven, commissioned and validated. These breakdown packages may be identified as use cases. Each integration vision or outcome is realized after each group of use cases associated with an outcome is commissioned.

Communicating and coordinating use-case scope to the project team is critical, so work is included in the project documentation and represented in a clear format for the contractors completing the work. Because integration by its nature includes more than one party or system, it is important to tie each element or breakdown package to milestones or events in the project design and construction schedule life cycle to ensure follow through.

Each integrator lead person is required to have both technical and communication strengths to execute a disciplined and measurable process that is supporting the outcomes of the integration vision throughout the project life cycle.

Tim Koch, PE, is a vice president and engineering principal at HDR in Omaha, Neb.; and Brian J. Spencer, AIA, is executive director of campus development and real estate campus architect at Nebraska Medicine/UNMC in Omaha. They can be reached at tim.koch@hdrinc.com and brspencer@nebraskamed.com.