How to measure employee productivity

It’s best to use a person’s current job competencies as the baseline model while quantitatively evaluating their performance.

Image by Getty Images

Outcome is not the same as output, though both metrics represent productivity. Output is what most people traditionally consider when they think of productivity. It’s essentially the deliverable or product that results from work. Output’s efficiency is measured with throughput — the rate at which someone produces the final product. An outcome is the result or impact of work, and its effectiveness is measured in value. The outcome is important because it’s possible for a team to work long hours and produce numerous widgets of no or little value, which is low output.

Work itself starts with the outcome, and most people think of that as a goal. Once goals are set, the skills necessary to produce that outcome are identified. From there, a staffing plan is produced and resources are allocated to fulfill the work plan. Measures like volume and completion rates predict the future output. Other measures such as quality and value predict the final outcome.

In health facilities management, the output might be the number of work orders completed per person per month. At face value, it might seem like the employee who closes the highest volume of work orders is the most productive or efficient. Although that could be the case, it could also be true that the same employee has the highest number of callbacks because work orders are not addressed with high-quality service.

This is why it’s important to view trend data and understand how employees are spending their time out in the field. Customer satisfaction and work order callback percentages would measure the work’s outcome. If customer and patient satisfaction scores are high and throughput targets are met, then it’s likely that the worker is performing at a high level of productivity and efficiency.

Nothing is more influential to successful output and outcome than skill. Employee proficiency and efficiency are critical to all work. Because not everyone has the luxury of fully evaluating their employees’ efficiency and proficiency levels before their hiring, managers should continuously evaluate their team’s performance with qualitative and quantitative metrics.

Macro measurements

It’s never too late to revert to ground zero and ask, “What do we want to accomplish?” Again, the answer to this question determines what skills are required for success, and these skills are grouped and categorized as job competencies that are memorialized in job descriptions. Alternatively, if the work is outsourced, the skills are organized as scopes of work.

The most opportune time to ask this question is during the annual review and strategic planning period. During this time, leadership compares the skills they have hired internally versus what is required to meet the next year’s goals. If gaps exist, managers decide which skills they will develop and hire internally versus skills that will be outsourced to qualified business partners.

In addition to the annual planning process, it’s critical that leadership routinely meets to discuss, evaluate and redirect their organization’s objectives. An organization can range in scale from a team, department, business unit or company. Leadership should represent all of the key services or skills necessary to achieve the organization’s goals or objectives. All perspectives are necessary to formulate a complete picture of execution and success.

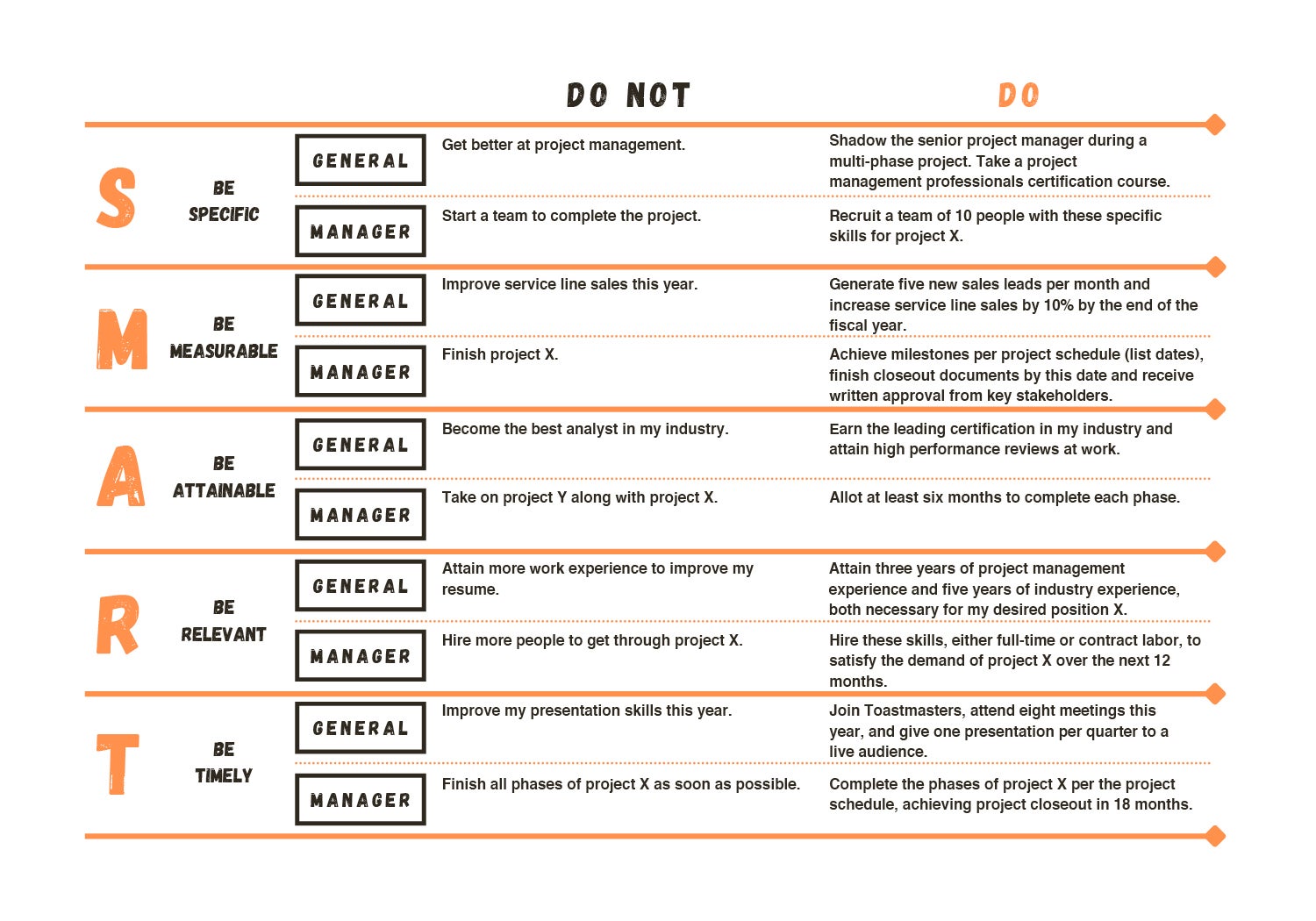

The SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-based) method is especially effective when establishing goals because it offers a way to objectively monitor performance. It’s not enough to say that the organization will increase performance quality. How will this be measured — customer satisfaction scores? By what percentage and when? Is that the “true north” metric for that department, or is another metric more critical to measuring success? And at what point does financial performance outweigh mission or quality, or does it ever?

Metrics are derived from all of the SMART components, especially specific and time-based — this specific thing will be achieved by this time. Otherwise, the team is left with ambiguous goals that ultimately lead to mediocre performance and results.

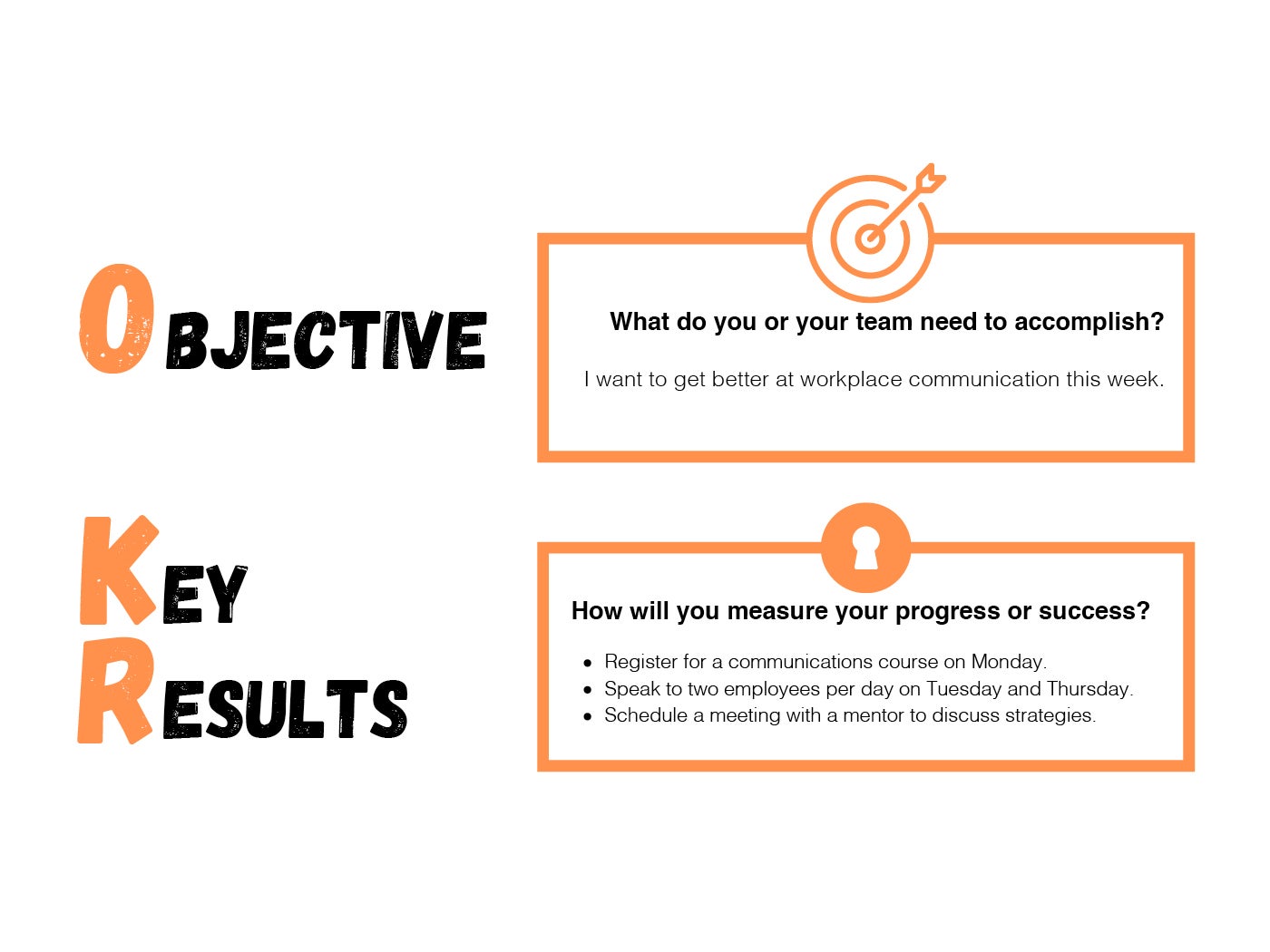

The OKR (objectives and key results) method recommends that leadership establish weekly goals for the team, usually in the form of output. These key results are tasks or measures necessary to achieve the organization’s strategic goals (objectives), usually recognized by their outcome. Essentially, key results measure and predict the success of objectives and are typically numbered as few as possible — ideally no more than five.

At the end of the week and before setting goals for the following week, the leadership team will review the organization’s production and determine if the goals were met. If the goals were not met, then the team identifies the barriers that prevented success so they can use this information to inform future key results. The team also evaluates the probability that each strategic goal will be satisfied and adjusts this probability from week to week based on the interim key results. Progress and performance are routinely evaluated so that course corrections can be implemented quickly and nimbly.

At a less frequent interval, such as quarterly, the leadership team meets off-site for strategic planning purposes. The meeting should be away from the office to avoid distraction and promote intention, focus and collaboration. Here, leadership evaluates performance for the last interval (in this example, the last quarter) and sets new objectives for the next one. The weekly goals compound to support progress for the interval goals that support progress for the long term or annual goals that ultimately support the organization’s mission.

The OKR method recommends that leadership establish weekly goals for the team, usually in the form of output.

Graphic by the author

For more information about different approaches to team meetings, Patrick Lencioni and his publications are a fantastic resource. Additionally, the book Radical Focus: Achieving Your Most Important Goals with Objectives and Key Results by Christina R. Wodtke is a must-read for understanding and applying the OKR model.

Micro measurements

Goal progress and achievement are determined by the team’s skill set and level. While quantitatively evaluating a person’s performance, it’s best to use their current job competencies as the baseline model. After all, that is the work they have been contracted to perform.

If the job competencies are not specific enough to use for this purpose, it might be time to update their job description. Competencies should be specific, relevant and measurable. The person’s proficiency level in each competency can be measured with a demonstrative checklist (demonstrate that they can perform this specific task) or determined by their ability to meet their performance targets, sometimes referred to as key performance indicators.

If the checklist method is used, it should closely mirror what is in that person’s job description. Not all tasks will be evaluated as a pass or fail. Some tasks might be evaluated with a range (0% to 100% proficient), and the benchmark for each interval will need to be clearly defined.

If the metric method is used, they can be tiered so that a minimum, bonus and stretch target are defined. These metrics could include throughput rates, budget and schedule targets, customer satisfaction survey results, hand-hygiene performance and others. Many budget targets are represented by a cost-per-square-foot value. In health care support services, other performance indicators could be closely tied to compliance, safety, infection prevention and infrastructure goals.

Alternatively, a person’s proficiency in their job can be measured quantitatively and objectively with an assessment. Although testing employees can seem like a daunting task that could end with a coup, it does offer a fair, consistent method for evaluating similar roles against the same knowledge base.

Some managers might choose a blended approach that combines demonstrative performance with tested knowledge. Regardless of methodology, managers must act on this data. They should use it to determine internal training opportunities, hires, promotions and outsourced scopes of work. This process should be repeated annually or each time new goals are established for that team.

If training is necessary to close proficiency gaps, the results of that training will need to be evaluated and documented. Preparing for an assessment via cramming and textbook tactics rarely results in lasting knowledge. These exercises demonstrate that a person can perform well enough on an exam and retain that knowledge for a limited period of time. Although they demonstrate a certain proficiency level, earned certifications and successful exam results do not necessarily correlate to work performance.

A post-training knowledge check should verify short-term retention. This demonstrates the person’s initial understanding of the new information or skill. Long-term retention should also be verified at least once, if not annually, to prevent knowledge degradation, which would then necessitate remedial training. These periodic knowledge checks are especially important if the new information or skill is not immediately or often applied to that person’s regular work.

Quantitative evaluations offer a partial picture of someone’s skill set. The other part includes qualitative measures such as attitude, engagement and cooperation. They should closely mirror the organization’s values and required team attributes.

Proficiency in these areas is determined with observed behavior by as many perspectives as possible — from every direction within the organizational chart. This 360-degree viewpoint identifies whether issues are isolated to a relationship, individual or hierarchical prejudice. If discrepancies exist, it’s important to understand the person’s motivators, demotivators and social biases so that their work can be adjusted accordingly.

Anonymous employee satisfaction surveys offer personal insight that can help inform leadership on the quality of its work culture. Even a highly skilled individual can perish in a toxic work environment, meaning their work quality and throughput will suffer or they will find a better-suited position elsewhere. It’s important to be mindful that a person’s work performance and productivity can widely vary based on their work environment, including their leadership and teammates.

It’s also important that historical trend data is thoughtfully captured and documented because most managers are inclined to use recent data to evaluate performance. A person’s productivity could have recently changed because of temporary personal circumstances or they recognize that employee evaluation time is approaching. A limited dataset could skew a manager’s reasoning. As they say, history predicts the future.

Achieving the goal

In his book The Goal, Eliyahu M. Goldratt teaches that the primary goal of an organization is to make money. Activity that results in making money is productive, and activity that doesn’t make money or, worse, loses money, is unproductive. Even philanthropic, not-for-profit organizations like most hospitals need to generate enough income to support their mission of healing.

Because health care facilities management does not directly generate revenue but supports the business operations that do, this concept of productivity can become ambiguous if the success of that department is not measured by outcome and output. When the output of the department generates outcomes that support making money, it’s successful.

Many health care facilities departments lack recognition for their success because not enough attention is placed on their outcomes — just output. With the right metrics in place, and the right platform to communicate their progress toward these goals, health care support services will gain the traction they need to thrive, including the precious talent to get the work done.

Lindsey Brackett, CHC, CHFM, SASHE, is president and co-founder of Legacy FM, Little Rock, Ark. She can be contacted at lbrackett@legacy-fm.com.

About this article

This is one of a series of monthly articles submitted by members of the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s member tools task force.