Managing deferred maintenance at rural hospitals

Approximately 57 million rural Americans depend on their hospitals as an important source of care as well as a critical component of their area's economic and social fabric. Location, size, workforce, payment and access to capital challenge small or rural hospitals and the communities they serve. The American Hospital Association (AHA) ensures the unique needs of rural members are a national priority.

One of the collaborative efforts the AHA uses to help rural hospitals and the communities they serve is the AHA Rural Health Care Leadership Conference. More than 1,000 people attended the 35th annual conference in Phoenix last February bringing together rural hospital CEOs, senior executives, clinical leaders and trustees to share strategies and resources for accelerating the shift to a more integrated and sustainable rural health system.

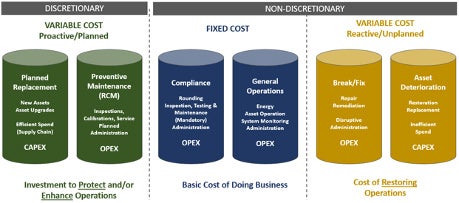

One of the key presentations at the conference presented by Mark Mochel, MBA, PMP, CSM, FCT, ACABE, co-founder and senior vice president, Facility Health Inc., and Jonathan Flannery, MHSA, CHFM, FACHE, FASHE, senior associate director, advocacy, American Society for Health Care Engineering, focused on infrastructure capital planning. With the current focus on infrastructure funding, it is hard to know how to appropriately fund this important part of the physical environment. The presentation focused on the four types of infrastructure expenditures and how these are divided into discretionary and non-discretionary spending.

The non-discretionary spend within a health care facility’s infrastructure evolves around the fixed costs of general operations and compliance (the blue buckets indicated in the graphic below), and the variable costs of asset deterioration and break/fix costs (the yellow buckets). Examples of the fixed costs are utilities, asset operation, system monitoring, etc., along with the cost to remain in compliance with the codes and standards required by accrediting organizations such as mandated inspection, testing and maintenance (ITM) efforts. Variable costs are those needed to repair items that break or to upgrade those assets that are no longer efficient or able to perform as needed. These costs are the basic facility cost of doing business and must be properly funded in order to keep the facility in compliance and up and running.

The discretionary spend within a facility’s infrastructure are those attributed to preventive maintenance and planned replacement (the green buckets). Examples of preventive maintenance are those activities above and beyond mandated ITM efforts that help to extend the life of an asset or to maintain the asset in a more efficient and functional mode of operation. Planned replacement are those activities which are scheduled in advance and are sometimes also known as non-recurring repair and maintenance or NRM activities. Unlike variable costs that are unplanned, NRM activities are planned and typically larger in scale to take advantage of cost savings based on the planned activity or size of scale.

Image courtesy of Jonathan Flannery

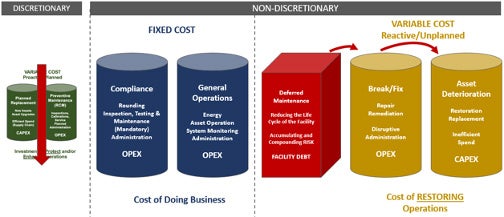

The one specific area the presentation focused on was what a facility should do when it is not able to provide all the funding necessary to address both the non-discretionary and discretionary costs a facility has. These non-funded activities are termed deferred maintenance, which is defined as “infrastructure assets that have exceeded industry expected useful life based on age and/or condition.” These assets are not in an imminent failure mode, but indicate an accumulation of risk, and should be evaluated carefully for renovation and/or replacement or continued service.

Deferred maintenance is a risk strategy that can be employed by a facility to extend the facility’s infrastructure investment. The risk comes in the reality that as deferred maintenance increases due to the continued deferral of discretionary funding, the risk of variable costs needs also will increase due to the increase in variable costs in restoring infrastructure services through additional break/fix and asset deterioration.

Image courtesy of Jonathan Flannery

The more assets’ maintenance is deferred the more assets will fail. This, as indicated by the graph above, increases the need for non-discretionary variable costs. To avoid this, an organization will need to work as a team to ensure that sufficient infrastructure capital planning (the green buckets) is allocated on a regular basis to to maintain the deferred maintenance risk at an acceptable level.

While nationally there is a trend in deferred maintenance escalation, the presenters encourage rural health care facilities to pay close attention to the impact that this increase will have on their ability to provide services to the communities they serve. By working together with facility experts, health care administrators can develop an infrastructure capital planning strategy that will manage deferred maintenance at an appropriate risk level.