Stop spread of <em>C. difficile</em>? Methods matter, research shows

Increased activity to prevent the spread of Clostridium difficile, which is linked to thousands of deaths annually, is failing to reduce infection rates, which have reached historically high levels.

That's the finding of one recent survey. But another study shows that the person who cleans and disinfects patient rooms and how it is done can make a difference in controlling the deadly bacteria.

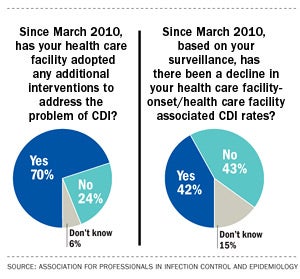

According to a recent survey by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), 70 percent of respondents said the hospital in which they work has adopted additional interventions to address the problem of C. difficile infections (CDI).

Yet, only 42 percent witnessed a decline in their CDI rates during that period, while 43 percent did not see a decline, according to APIC's 2013 CDI Pace of Progress survey conducted Jan. 14–28, 2013. Survey results were presented in March at APIC's Clostridium difficile Education and Consensus Conference

in Baltimore.

While cleaning activity has increased, monitoring the results has not kept pace, the survey reported. While 92 percent of respondents have increased emphasis on environmental cleaning and equipment decontamination, 64 percent said they rely on observation instead of more accurate monitoring technologies to determine cleaning effectiveness. Fourteen percent said that nothing was being done to monitor room cleaning.

Because C. diff spores can survive in the environment for many months and are highly resistant to cleaning and disinfection, environmental cleaning and disinfection are critical to prevent the transmission of CDI, APIC says.

But how it's done makes a difference, notes a study published in the May issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal for the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. The study describes the importance of establishing a rigorous cleaning and monitoring regime to control C. diff.

The study notes that a dedicated daily cleaning crew who uses a standardized process to clean and disinfect rooms contaminated by C. diff can be more effective than other disinfection interventions.

The cleaning crew used fluorescent markers to monitor cleaning effectiveness, an automated ultraviolet radiation device and bleach wipes to augment disinfection after cleaning. A combination of the dedicated cleaning crew and enhanced methods reduced the presence of C. diff in patient rooms by 89 percent during a 21-month study conducted at the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The cleaning crew used fluorescent markers to monitor cleaning effectiveness, an automated ultraviolet radiation device and bleach wipes to augment disinfection after cleaning. A combination of the dedicated cleaning crew and enhanced methods reduced the presence of C. diff in patient rooms by 89 percent during a 21-month study conducted at the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

There are 337,000 hospitalizations for C. diff annually in the United States and C. diff is linked to about 14,000 deaths, adding at least $1 billion in health care costs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jennie Mayfield, clinical epidemiologist, Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, and president-elect, APIC, says science about C. diff's multiple strains and how the pathogen moves among populations remains a mystery.

"I think until we answer some of those basic questions, hospitals are going to continue to do what seems to work in their individual facilities. It becomes a case of my hospital is doing one thing and the hospital next door may do something else to prevent the spread," she says.

Mayfield says that experts suspect that patients may remain colonized with C. diff and continue to shed the bacteria for an undetermined period after symptoms evolve.

"Those persons could be a source of new infection if they're not isolated. So we may need to prolong isolation; we may need to screen people on admission. None of that's happening right now," she says.

Mayfield is encouraged by ongoing research that shows promise for a vaccine that may prevent infection. Persons who are colonized with a nontoxigenic strain of C. diff don't get the toxigenic strain, so it's possible that being colonized protects them from infection. Patients who are admitted or readmitted to the hospital would be vaccinated as a safeguard.