Using the RCM process for hospital equipment

Starting with a full study of air-handling systems will provide the basics for developing an understanding of the process and allowing for a paradigm shift to an RCM mindset.

Photo by H. Schipper

Anthony M. Smith, co-author of the book, RCM — Gateway to World Class Maintenance, was one of the first users of reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) after it came out of United Airlines, and he teamed up with Thomas D. Matteson to help fix the Three Mile Island nuclear reactors.

Later, as a mentor and guide, he helped bring the concept of RCM into the health care field. Along with others, such as Jack R. Nicholas Jr., PE, CMRP, CRL, CAPT USNR (Ret.), Smith showed health care facilities professionals how they could bring their maintenance programs up to world-class and high-reliability standards.

Although Smith passed away in February before he could see his efforts fully blossom in health care, he remains one of the giants upon whose shoulders health care facilities professionals stand to see higher and farther.

Regulatory changes

On Dec. 2, 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of Clinical Standards and Quality/Survey & Certification Group issued Survey and Certification (S&C) letter 12-07-Hospital.

The subject of the letter was “Clarification of Hospital Equipment Maintenance Requirements” and the substance was to inform hospitals that they must follow manufacturer’s recommended techniques for maintaining equipment and that alternative equipment maintenance methods are not permitted.

The only exception to this rule permits alternate equipment maintenance schedules based on appropriate assessments of risk. The letter updates the guidance of Appendix A of CMS’s State Operations Manual for Section 482.41(c)(2) of the regulations.

In December 2013, S&C letter 14-07-Hospital superseded this previous directive by allowing hospitals to deviate from the requirement of maintaining equipment using only manufacturer’s recommendations (MRs) to an option of using MRs or providing an alternate equipment management (AEM) program for most, but not all, equipment.

This option allowed a flexibility of choice for most equipment meeting certain risk criteria that was welcomed by most facilities.

Essentially, with few exceptions, it allowed facilities to resume maintenance operations using the protocols that were in place in their facilities before the earlier directive.

The acceptance of “no change necessary” without realizing some of the nuances of the new directive can be a source of confusion and noncompliance related to its finer points. These can be seen in how the individual state departments of health have changed their regulations and in updates to The Joint Commission (TJC) standards.

Additionally, it needs to be realized that the new directive and its implementation by TJC and the states is not logically straightforward and requires some thought to provide an appropriate implementation.

The following guidance may be useful to understanding how the regulations and standards relate to each other and how RCM fits in this new structure:

- CMS. The “Background Information on Types of Maintenance Strategies” section of the State Operations Manual attached to the Dec. 20, 2013, S&C letter 14-07-Hospital describes four major maintenance methodologies acceptable for AEM programs if the hospital elects not to use the MRs in some areas.

The four major methodologies that are described are preventive maintenance (PM), predictive maintenance (PdM), reactive maintenance (RM) and reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) (see the sidebar on this page).

The AEM option is allowed for most equipment except radiological equipment, lasers and equipment for which staff has no maintenance knowledge. These items must remain under MRs. Only new equipment about which staff has gained sufficient maintenance knowledge may be moved from an MR to an AEM program.

Each methodology is presented with a brief definition of its strategy but, without delineation, the description leaves the impression, at first glance, that all four are of equal value. Although RCM is included as one of the four and roughly defined, its relationship to equipment function is mentioned without reference to its status as a TJC performance improvement process relationship, which drives the other three maintenance methodologies to “world-class,” as exceptional maintenance processes are sometimes called.

PM, PdM and RM are foundational, traditional programs used for equipment. They can stand on their own merits, with outcomes that are traditionally acceptable.

PdM also is known as and is synonymous with asset condition monitoring (ACM). Although PdM/ACM is a powerful maintenance tool, it is not RCM, which is a popular misconception. (RCM as a performance improvement process drives the efficient and effective use of PdM and the other strategies.)

RCM methodology has been proven outside health care and can be shown to be critical in significantly increasing the reliability and significantly reducing the costs of maintaining the function after the analysis is completed. Currently, there are several RCM startup processes in hospitals that are being advanced beyond their initial setups to becoming fully operational systems. Historically, this form of RCM, sometimes called “classical RCM,” is in full use in airline, nuclear power, nuclear navy and other operations.

RCM provides the opportunity to step away from traditional maintenance programs and move toward TJC’s goal of high reliability and robust process improvement. The time and effort in doing so produces a program that can be truly classified as high-reliability and world-class.

Finally, hospitals typically do not have the level of criticality of some other enterprises nor the large footprint of other industrial facilities, such as those in manufacturing or refineries, leaving fewer opportunities to apply a complete RCM study.

Starting with a full study of air-handling systems will provide the basics for developing an understanding of the process and allowing for a paradigm shift to an RCM mindset. This shift in understanding provides a mental format for evaluating the functions and needs of simpler functional systems and equipment that do not require a full RCM analysis.

The RCM process supplies the tools that support modified studies without using the entire analytical process. In learning the process well, the principles become part of a mindset that can be recalled, readily applied and significantly administered for highly reliable and world-class results using the paradigm shift that has occurred in thinking when focusing on functional reliability.

In any case, planned run-to-failure maintenance should not be included as reactive maintenance because it is planned!

- State. The previously discussed section of the State Operations Manual titled “Background Information on Types of Maintenance Strategies” has a second purpose. It is named “State Operations Manual” because all states that contract with CMS for validation and “for-cause” surveys must incorporate all mandates of the manual found in “Appendix A — Survey Protocol, Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines for Hospitals” into their role as a CMS contractor in their oversight of hospitals receiving Medicare funding.

Prior to 2014, Medicare nonclinical regulations emphasized compliance with the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code® (LSC). They gradually added other technical and environmental areas of concern by referencing what was originally Appendix B “Non-mandatory References” in the LSC.

Before and during this time, the states and TJC were able to make their own regulations affecting the hospitals’ nonclinical, technical and environmental areas. These activities resulted in several code variations that could be found in conflict with each other.

Now, with CMS providing specifics on maintenance strategies, the states, based on their past level of regulation-making activity, needed to provide various levels of response to this mandate. This includes having to create or modify regulations to meet the CMS directives. (Hospitals that are not under Medicare can be held to state regulations solely.)

California, for example, has removed the program flexibility applications for all the affected regulations, replacing the process with a note stating that if it fits the S&C letter’s guidelines, no program flexibility application is required or accepted. It also allows nonresponse for regulations that haven’t been changed but are known to be outdated.

Ultimately, any modifications of programs to meet the new CMS maintenance strategies must include a review of the state’s licensing regulations to determine their impact on the hospital’s program.

- TJC. Prior to Medicare, TJC was an independent professional organization whose accreditation process had gained status in the health care world. With the advent of the Medicare regulations, their abilities were recognized by the government and the organization was written into the act, allowing TJC to continue to perform independently, their accreditation accepted by CMS as fully meeting CMS’s regulatory process.

Around 2010, a change was made that now requires TJC to apply for the status they once had with much more scrutiny being given to standards and survey results. With the advent of S&C letter 14-07, TJC was required to alter its standards to match CMS regulations.

The RCM process

Because RCM is a new methodology to many hospitals and because it is a complex process to implement, it has been subject to many misconceptions. To dispel some of these misconceptions, the following points have been developed through discussions with the previously mentioned Jack R. Nicholas Jr., author of the book, Asset Condition Monitoring Management.

- RCM is an acceptable maintenance strategy for presentation at surveys and inspections. CMS has recognized RCM as a viable maintenance strategy in its update of the State Operations Manual (S&C 14-07-Hospitals). Because the source is CMS, all states and accrediting agencies are required to accept RCM as a viable “maintenance strategy” (CMS terminology) in all Medicare hospitals.

- RCM is not indiscriminate. Placing vibration sensors on everything that rotates provides data but does not allow for easy analysis for “real” events. Without an RCM analysis that shows which pieces of rotating machinery to monitor because of their critical function, much time and cost will be wasted on noncritical machinery and components.

- RCM adds value to work. When introduced to RCM, many see the tool stripping the maintenance program of procedures and instruction sets that were being used to manage the equipment’s and function’s reliability. Using the examples that can be supplied from the pilot hospital sites, it was discovered that where procedures were removed, they were often replaced with more meaningful procedures enhancing the reliability of the equipment functions. The result was no lost work that wasn’t replaced with more meaningful work.

- RCM is a maintenance program that relates to the hospital’s quest for quality and high reliability. Somewhere during the RCM concept development that spawned this article, a source said, “RCM is a maintenance management strategy with a quality cycle attached.”

Upon examination, it is parallel to the TJC performance improvement cycle of data collection, data analysis and performance improvement. For those who have wondered how to match a hospital’s efforts in proving quality and high reliability, they will see that RCM is in lockstep with the performance improvement chapter of TJC’s manual.

- PdM is not RCM. The thought that PdM is RCM relies on the misconception that using advanced testing equipment provides data that is actionable for providing high reliability. Maintenance done without an analytical pathway for preserving system function cannot be called RCM.

- RCM does not require PdM as its only endpoint for equipment maintenance in doing an RCM analysis. All three of the other maintenance strategies are in play (PM, PdM, RM) until the RCM analysis and procedure phase is complete. This process also can include the option of planned “run-to-fail.”

According to Nicholas Jr., there are basically five PdM tools that can be used in implementation, but all three methodologies offer candidates for the instruction sets. The one selected is based on the one that is the least invasive and most economical.

The bottom line

RCM is not a maintenance strategy but a quality management process from which a world-class maintenance strategy is derived based on the application of the RCM analysis process on system and equipment functions.

Classical RCM is the quality improvement process that can make health care facility maintenance world-class.

CMS’s descriptions of acceptable alternate maintenance programs

The “Background Information on Types of Maintenance Strategies” section of the State Operations Manual attached to the Dec. 20, 2013, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Survey and Certification letter 14-07-Hospitals describes four major maintenance methodologies acceptable for alternate equipment maintenance programs if a hospital elects not to use manufacturer recommendations in some areas. They are described by CMS as follows:

- Preventive maintenance (time-based maintenance). A maintenance strategy where maintenance activities are performed at scheduled time intervals to minimize equipment degradation and reduce instances where there is a loss of performance. Most preventive maintenance is “interval-based maintenance” performed at fixed time intervals (e.g., annual or semiannual), but may also be “metered maintenance” performed according to metered usage of the equipment (e.g., hours of operation). In either case, the primary focus of preventive maintenance is reliability, not optimization of cost-effectiveness. Maintenance is performed systematically, regardless of whether it is needed at the time. Example: Replacing a battery every year, after a set number of uses or after running for a set number of hours, regardless.

- Predictive maintenance (condition-based maintenance). A maintenance strategy that involves periodic or continuous equipment condition monitoring to detect the onset of equipment degradation. This information is used to predict future maintenance requirements and to schedule maintenance at a time just before equipment experiences a loss of performance. Example: Replacing a battery one year after the manufacturer’s recommended replacement interval, based on historical monitoring that has determined the battery capacity does not tend to fall below the required performance threshold before this extended time.

- Reactive maintenance (corrective, breakdown or run-to-failure maintenance). A maintenance strategy based upon a “run it until it breaks” philosophy, where maintenance or replacement is performed only after equipment fails or experiences a problem. This strategy may be acceptable for equipment that is disposable or low-cost and presents little or no risk to health and safety if it fails. Example: Replacing a battery after equipment failure when the equipment has little negative health and safety consequences associated with a failure and there is a replacement readily available in supply.

- Reliability-centered maintenance. A maintenance strategy that not only considers equipment condition, but also considers other factors unique to individual pieces of equipment, such as equipment function, consequences of equipment failure, and the operational environment. Maintenance is performed to optimize reliability and cost-effectiveness. Example: Replacing a battery in an ambulance defibrillator more frequently than the same model used at a nursing station, since the one in the ambulance is used more frequently and is charged by an unstable power supply.

Download the entire document to learn more.

Modified CMS methodology

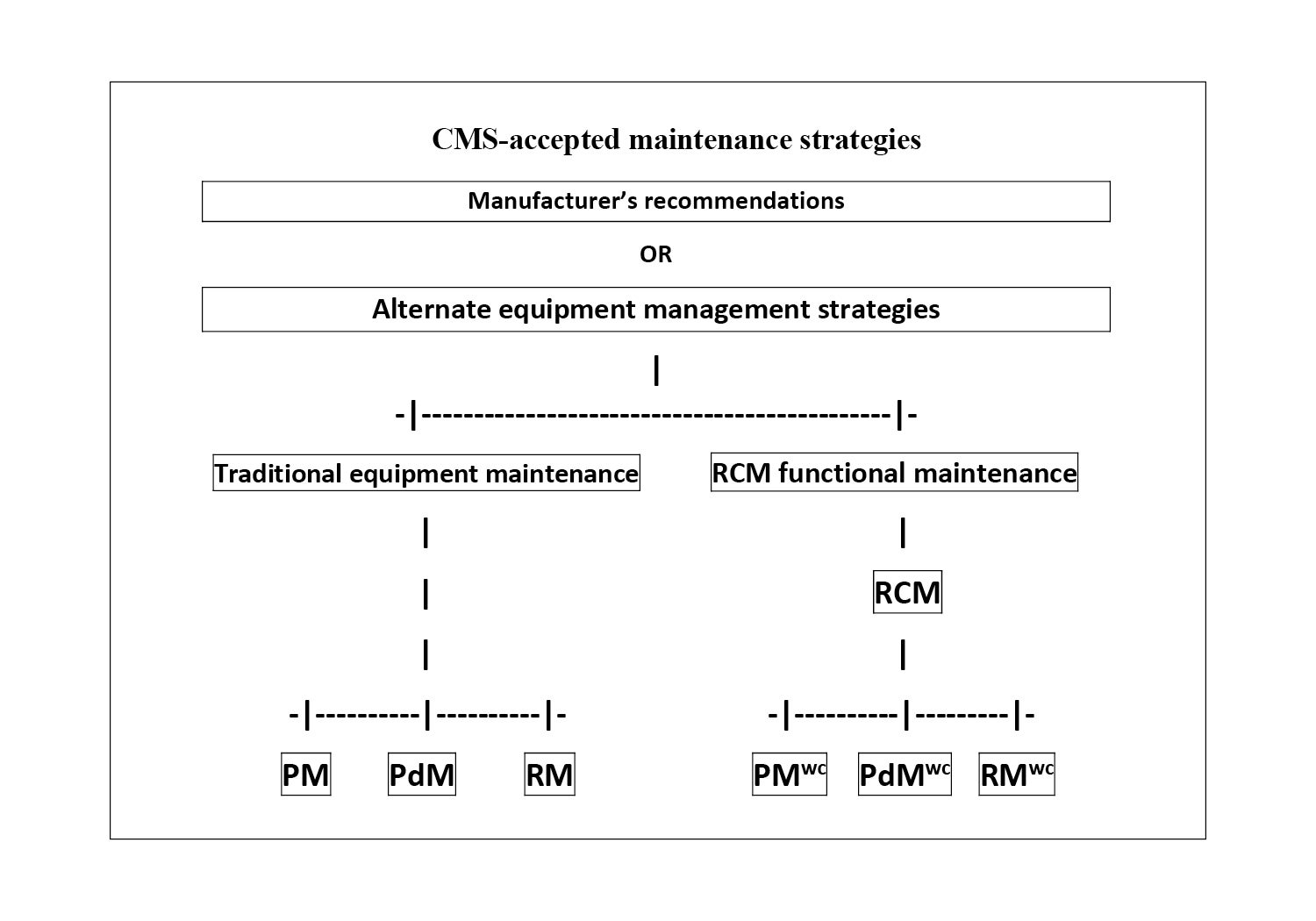

This enhanced sketch (below) fills out the didactic of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Survey and Certification letter 14-07-Hospitals, which describes four major maintenance methodologies acceptable for alternate equipment management programs if the hospital elects not to use the manufacturer’s recommendations in some areas.

In the graphic, RCM stands for reliability-centered maintenance, PM stands for preventive maintenance, PdM stands for predictive maintenance, and RM stands for reactive maintenance. The WC superscript indicating “world-class” is to demonstrate the instruction set is the result of an RCM analysis.

The RCM box is not replaced with a formula, but with an seven-step analytical process that provides a unique solution for each function of an identified system.

It is parallel to The Joint Commission’s performance improvement cycle of data collection, data analysis and performance improvement. From this analysis, specific failure modes are identified, documented and prioritized.

In turn, candidate maintenance actions that will be applicable and effective are identified and instruction sets for maintaining those functions to be preserved are assigned to PMWC, PdMWC and RMWC instruction sets.

W. Thomas Schipper, CCE, FASHE, is manager of environmental risk for Children’s Health of Orange County, Orange, Calif., and Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance, Calif. He can be reached at wtschipper@gmail.com.