The business value of infrastructure

Translating engineering needs into business outcomes is critical when engaging nonfacility leadership.

Image by Getty Images

The health care field has historically underinvested in infrastructure. It is a documented fact substantiated by increasing age-of-plant statistics first published by the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) in the 2017 monograph, “State of U.S. Health Care Facility Infrastructure.” .

The conclusion in 2017 was that the increase in median average age of plant of nearly three years over the past two decades indicates that hospitals, in general, have struggled to raise the capital needed to keep their facilities up to date.

Authored in the pre-COVID-19 era, it provides an excellent baseline from which to discuss infrastructure investment challenges today.

As a parallel statistic, facility condition assessment data collected by Brightly, a Siemens company, from 2016 to the present, suggests that up to approximately 47% of major mechanical, electrical and plumbing assets have exceeded expected useful life. Extrapolated to the national level, unless individual assets have been well maintained, this metric indicates there may be a significant number of infrastructure assets with an increased probability of failure based on either age, condition or both.

Assets in deferred status are not necessarily in imminent failure mode but otherwise represent an increasing liability for many health care organizations. Just as a car with 150,000 miles on the odometer may be running fine around town, that same vehicle may or may not be suitable for a family trip across the country.

Aging infrastructure increases risk, and the potential failure of key assets in critical environments can have devastating impacts on health care financial performance. In worst-case scenarios, they can also negatively impact clinical outcomes and patient care.

Now, in 2023, the lagging negative impacts of the pandemic in combination with other macroeconomic forces have created a perfect storm of conflicting investment priorities. “Normal” pre-COVID-19 infrastructure investment levels, already documented as insufficient, were cut further in the early years of the pandemic. Many of those cuts are now becoming permanent. Yet, even as the infrastructure continues to age, many facility leaders are being asked to harden, decarbonize and otherwise reimagine facility performance in ways that can only be achieved with significant capital investment.

Boiler room to board room

To justify and execute these transformational investment needs, health care facility leaders across the country must seek to establish stronger business relationships with nonfacility leadership and the C-suite. Now is the time to redefine facility needs in business terms and consider the adoption of nontraditional project and staffing validation concepts throughout the budget approval process. From the boiler room to the board room, three steps will assist in making that transition.

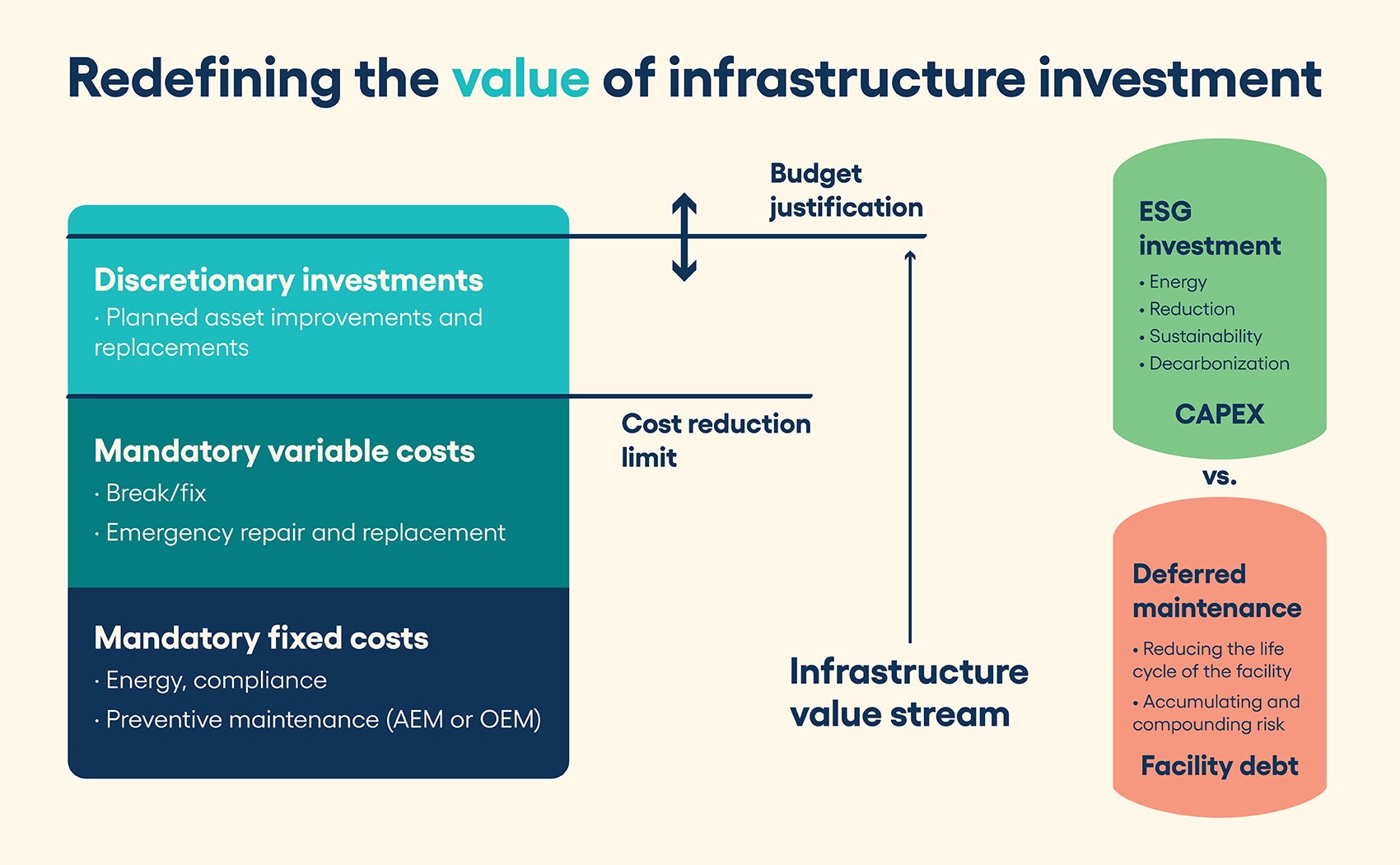

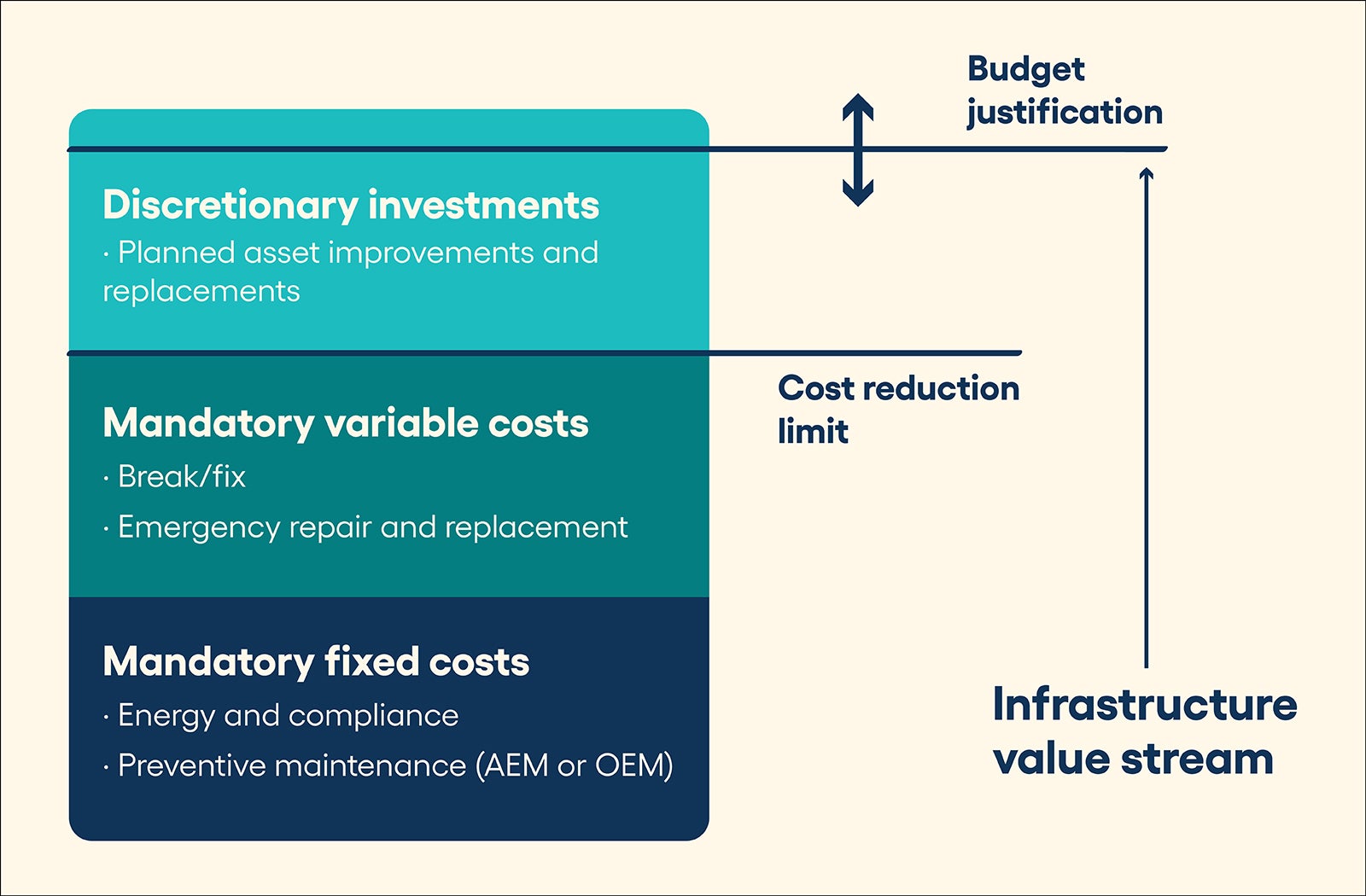

Step 1: Know the cost buckets when building a business plan for the facility. It is understood that health care facility departments are viewed as cost centers, and it is unlikely this perspective will change in the foreseeable future. However, the acceptance of this view creates significant and immediate capital committee barriers that can be difficult to overcome when communicating and comparing infrastructure financial needs to other investment options.

Tactically, it could be argued that the cost center label undermines or commoditizes the value of the facility itself and the work the facility teams do on a regular basis. Strategically, it perpetuates the false assertion that infrastructure investment provides no return on investment (ROI). A modern medical facility is a clinical asset, required to provide revenue-generating services, with clinical and facility operations fully integrated, co-dependent and mutually subject to ever-increasing regulatory pressures.

Perpetual cost-cutting is a race to the bottom and is unsustainable in the face of mandatory workload. Any organization that has experienced the financial losses associated with major infrastructure failures (e.g., a flooded emergency department) understands the ROI situation fully. At and after the point of an emergent failure, organizations will spend unlimited funds to restore operations as quickly as possible, and without ROI calculations to authorize funds. Why? Because after failure, the real or perceived ROI goes to infinity based on lost revenue, patient impact, accreditation jeopardy or a host of other “nonfacility” measures. Therefore, it is not inconceivable that somewhere between zero and infinity exist real and tangible ROI metrics that can be used to better justify infrastructure investment.

The goal then is to construct a meaningful business plan that is fully aligned around the key facility services that are valued by the organization. As with any business plan, understanding the true and total cost to provide those services is the first step toward establishing credibility. Using the bucket concept, consider the following major cost categories:

- Nondiscretionary, compliance and general operational expense (cost) enables deemed status and available hospital operations (value). These expenses include general operations (e.g., snow removal, groundskeeping and equipment operation); utilities (e.g., water, gas, electric, energy and waste removal); and mandatory life safety and environment of care compliance (e.g., inspection, testing and preventive maintenance). All of these services are required for basic hospital operations and, therefore, should be presented as a nondiscretionary cost. Understanding and documenting these costs, while demonstrating efficient deployment and management of resources, can provide a new foundation for more meaningful and transparent budget discussions.

- Discretionary operational expense improvement (cost) enables reduced downtime and extended life of capital equipment (value). For most assets, routine and mandatory preventive maintenance, whether manufacturer’s recommendations or alternative equipment maintenance, is required to meet the expected useful life projections. But there are other, more advanced maintenance techniques that can provide additional benefits. Predictive maintenance and reliability-centered maintenance programs can be used to further optimize and right-size maintenance efforts, further reduce equipment downtime, and significantly extend equipment life by eliminating unnecessary and sometimes harmful time-based preventive maintenance activities. Facility leaders who can identify the necessary investment of money, time and resources to achieve higher levels of performance as well as the associated improvements in operational efficiency, reduced equipment downtime and possible life extension of key assets may have more success in gaining executive support.

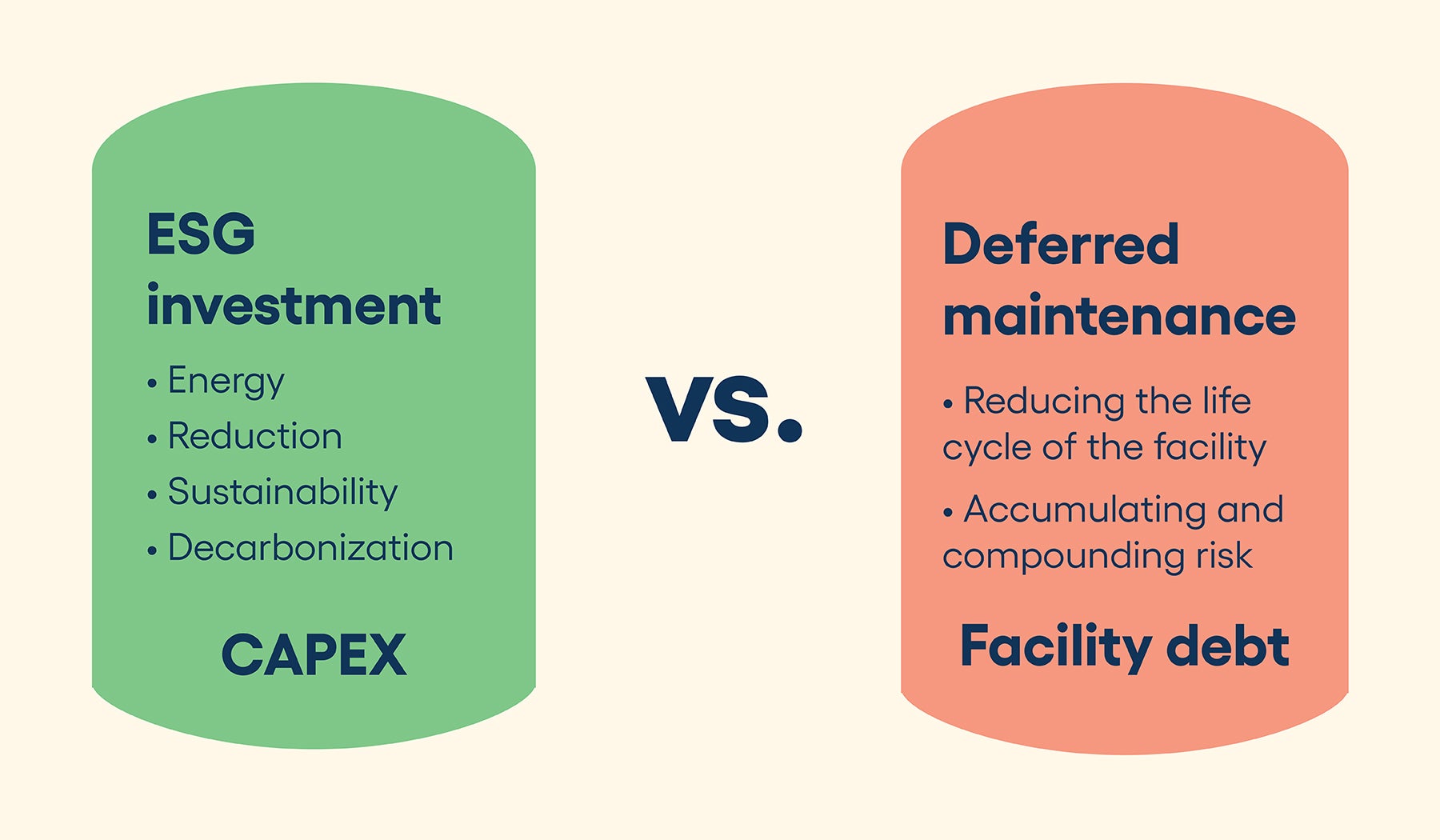

- Capital expense repair and replacement (cost) enables long-term facility stability and viability (value). Even with the best and most efficient maintenance practices, it is inevitable that some equipment must be repaired or replaced during a building’s lifetime. Yet, often, capital investment in infrastructure is seen as a zero-sum game. Capital requests denied in one year will either be forgotten or continue to resurface year after year, with the flawed assumption that there is no negative impact from nonfunded projects. Therefore, it is imperative that facility leaders consistently track and present both capital replacement needs and deferred maintenance levels as parallel measures so that nonfacility leaders can better assess the risk and impact of different investment options. It may be desirable and necessary in some years to fund nonfacility needs as a higher short-term priority, but with full visibility of the impact of those decisions, future infrastructure capital discussions can take place in a more transparent and collaborative manner.

Step 2: Link infrastructure assets to business needs and communicate risk in objective business terms to increase collaboration with nonfacility leadership. Taking the above business plan concept one step further, with a clear line of sight to both nondiscretionary and discretionary cost factors, it is then possible to align those costs with service lines, spaces and business outcomes that are impacted by the performance of those assets. Seemingly strange at first, this connection completes the ability to look beyond traditional cost center metrics and redefine infrastructure investments using value-based analysis and techniques.

Seasoned health care executives, perhaps more accustomed to reviewing income statements, balance sheets or other financial statements, may appreciate this approach and find it more relatable to other nonfacility projects also in review. There are only two ways to improve the financial performance of a department or business: increase the top line (revenue) or decrease the bottom line (cost) to sustain operations. With facility budgets already reduced to extreme levels, this budget growth or “revenue” concept may provide an opportunity to realign expectations.

As an example, an air handler that serves an operating room is not just a stand-alone asset; it is the heartbeat of a greater and more complex infection control system that is critical to patient care. The air handler, in combination with other key assets (e.g., dampers, diffusers and exhaust fans), provides the necessary air changes, sustains the sterile field and maintains the required temperature, humidity and pressure relationships known to reduce surgical site infections. In that context, the cost/value relationship is much easier to define.

Not every infrastructure asset has such a clear connection to either patient outcomes or business revenue, but even indirect links can be used in the same manner. Roofing, glazing and facades, when maintained properly, reduce or prevent water intrusion, which is also an infection control benefit. Identifying this path is a worthwhile endeavor. In summary, when preparing budget requests, document what the asset is, then define what it does and provide an objective assessment of risk if it fails. Every asset has a purpose, a cost and a value that can be defined when all three elements are understood.

Step 3: Align the facility business plan to the mission, vision and values of the organization and leverage data to integrate facility needs with other strategic initiatives. Depending on the culture of an organization, facility leaders may or may not be fully included in larger strategic investment decisions. Whether defined as a facility master plan or a strategic infrastructure plan, larger and longer-term facility decisions include service line projections, demographic forecasts, reimbursement levels and other financial metrics. When facility needs are framed in this financial perspective, it again may be possible to redefine the value proposition. Most hospitals and health systems have stated humanitarian, community and environmental values that can only be enabled through an efficient and viable infrastructure.

Of particular significance in 2023 is the increased emphasis on environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment. As of this writing, more than 60 hospitals and health systems have signed the Biden-Harris Health Sector Climate Pledge, committing those organizations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 50% by 2030, a massive effort that will require significant investment and major upgrades to existing plant operations.

This type of open commitment by an organization also represents an opportunity to further link facility operational and capital budgets to larger organizational initiatives and again question the perception that infrastructure investment has no ROI. In this case, ROI will be measured on the national stage as organizations meet these stated goals, or not.

If, in this example, decarbonization is important to the C-suite, then it is appropriate to include that factor when presenting projects and budgets for approval. It should be presented objectively, professionally and validated with meaningful data at all times.

Collaborative development

For many organizations, the financial challenges imposed by the pandemic have and will likely continue to exacerbate the problem of underinvested infrastructure for years to come. In parallel, facility leaders are being asked to harden facilities against natural disasters, reduce carbon footprints and reimagine the role of the facility itself in the future of health care.

As aging infrastructure, lack of available funding and physical infrastructure transformation are competing and contradictory goals, new investment priorities will be necessary, as will be the planning and budgeting processes used to justify that investment.

Transformation can only take place through the collaborative development of an objective business plan that can be supported and executed at all levels of the organization, from the boiler room to the board room.

Alternative financing considerations

As the world enters a transformational period for health care facilities, it’s important to look at alternative financing options. The traditional model of relying on cash, working capital or municipal bonds to finance facility upgrades may not be sustainable in the future, given the macroeconomic trends and financial health of individual organizations. Here are some other options to consider:

- Partner/vendor financing. Many suppliers of major mechanical, electrical and plumbing assets and systems can offer financing for equipment purchase, installation and operation. These financing options may be more competitive than capital accessed through other means.

- Utility provider grants/rebates. Many utility providers offer grants, rebates or other financial incentives for energy reduction projects. Organizations should explore these options for any project that can reduce energy consumption and generate a positive return on investment.

- Property assessed clean energy (PACE) state financing. More than half of U.S. states have enabled PACE financing, which provides access to capital with repayment administered through a tax assessment attached to the property. This funding mechanism may provide more options for energy-related projects if supported by a hospital’s state or local governments.

- Department of Housing and Urban Development Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Section 242 federal financing. The Office of Hospital Facilities administers the FHA Section 242 loan program. For qualified organizations, it may be possible to obtain an FHA-insured, nonrecourse, supplemental loan that can be used to fund capital improvement projects that specifically “reduce hazards and potential failures of key infrastructure assets.”

Regardless of the funding mechanisms an organization chooses, having documented asset needs, age and risk profiles, and business plans, will streamline any funding mechanism request. With data in hand, organizations can refocus on choosing the most desirable options to fuel infrastructure investments and health care facility upgrades.

About this article

This is one of a series of monthly articles submitted by members of the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s Member Tools Task Force.

Mark Mochel, MBA, CHFM, PMP, ACABE, is a strategic account executive at Brightly, a Siemens company. He can be reached at mark.mochel@brightlysoftware.com.