Improving sustainability through greater efficiency

Facilities professionals must gather the data, take decisive action, communicate results and build upon success.

Image by Getty Images

As most are aware, health care facility sustainability is a journey, not a discrete destination. It embodies not only sound design and initial construction but ultimately requires the installation of a continuous improvement mindset and culture to meet or exceed the desired performance of the health care facility year after year. People, processes and technology must all come together to “sustain” sustainability itself.

In that context, it is possible to expand the definition of sustainability to not only minimize the negative impacts of health care facilities on the external environment but also to fully optimize operations beyond the obvious energy and decarbonization goals. Also consider the potential to minimize the negative impacts of inefficient technology and poorly defined business processes on maintenance staff, patients, visitors and clinical outcomes inside the facility itself.

Waste is waste, whether measured on an energy meter, at an exhaust vent or by the inefficient deployment of human resources. Achieving the larger goals thus provides an opportunity to recalibrate internally as well.

Leveraging data

Health facilities professionals already engaged in running sustainable buildings have one thing in common: They understand both the necessity and opportunity of leveraging data to make better management decisions. As famously quoted by management author Peter Drucker, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” It is nearly impossible to operate modern facilities without continuous monitoring and automation of critical functions to detect and correct even the slightest deviations in performance. That same mindset applies to each element of a modern facilities management team.

With an understanding of what is required, it’s time to get to work. In simple terms, developing and deploying an efficient facilities management plan is like digging a ditch. The concept of the ditch is simple enough, but the real work starts only when the shovel goes into the ground. Once that happens, with each shovel full of earth, more is known about what is in the ground, learning takes place, and plans are adapted and modified based on real-world conditions.

It’s the same concept with a facilities management plan. But instead of digging in the ground, it’s about digging into the data, incrementally, intelligently and following a prescribed plan of action. Facilities professionals must complete each step in the following process before moving on, then make sound decisions on the next steps. Ultimately, they must follow the data, learn, adapt, modify and keep going until the work is done.

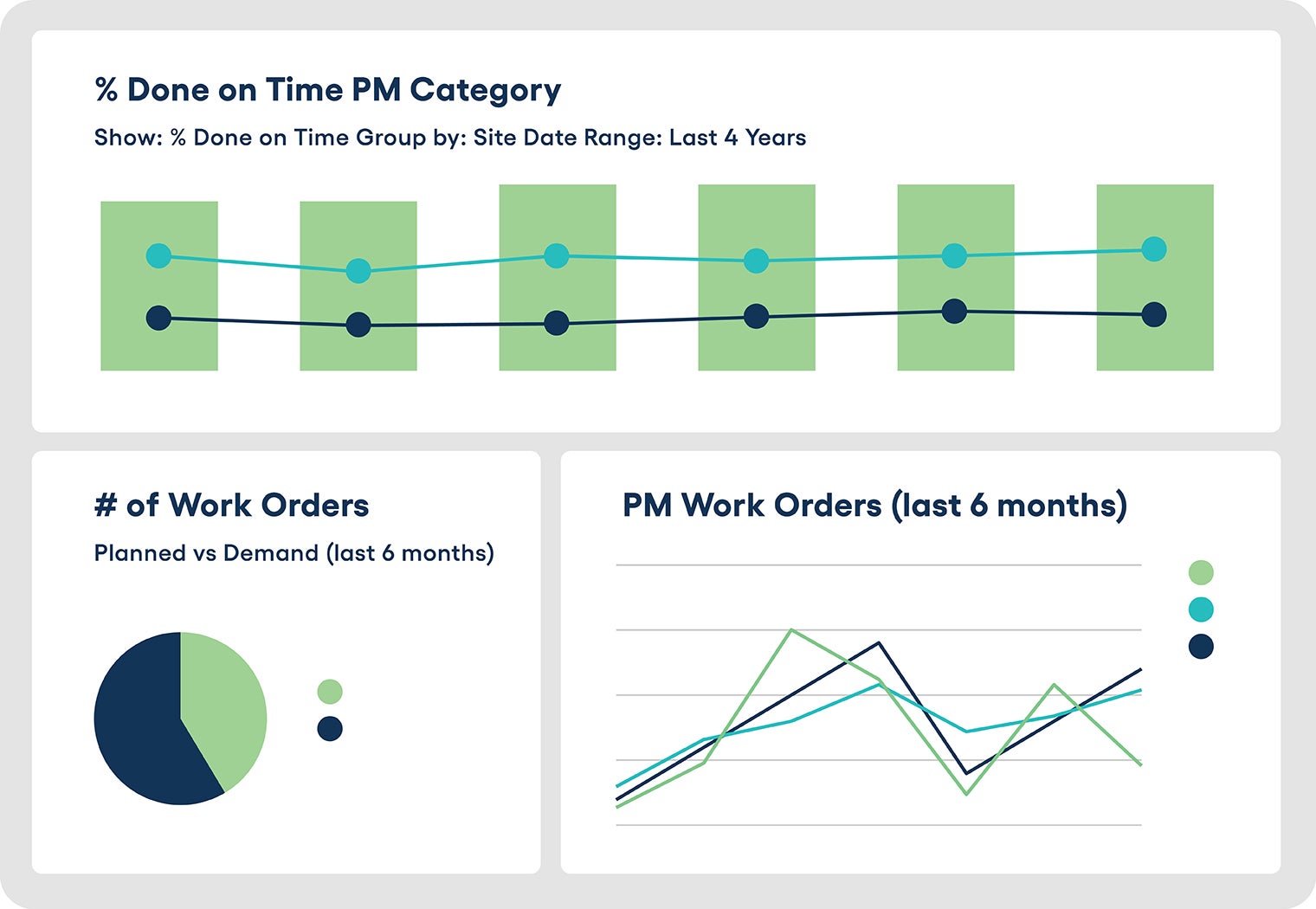

Step 1: Ensure data is centralized, organized and actionable. Before a facilities professional can begin to examine and evaluate how maintenance and operations plans impact sustainability efforts, it is important to start tracking data along the following three key performance indicator (KPI) pillars for energy and asset management:

- Planned maintenance completion. Regardless of strategy (i.e., preventive, predictive or reliability-centered maintenance), regular planned maintenance completion is one of the best energy-saving initiatives that an organization can make. When there is an appropriate amount of routine maintenance performed on assets, the assets will perform better and will last longer, as will the maintenance staff tasked with operating the facility.

By default, this lowers energy consumption by all measures. Premature and unplanned asset failures significantly increase costs, waste energy and are disruptive to overall operations. They are a burden on the bottom line and negatively impact the environment by consuming more energy, raw materials and labor. Establishing an accurate asset inventory and baseline condition of each asset is the only place to start.

What assets are in the building? How old are they? What critical functions do they support? How are they performing? What is the business impact if they fail? Having access to this basic data will inform stronger preventive maintenance plans — an important weapon in the arsenal to combat high energy utilization. Surprisingly, even in this modern era, many organizations do not properly maintain this basic foundational data. It is the basis from which all other metrics can be measured.

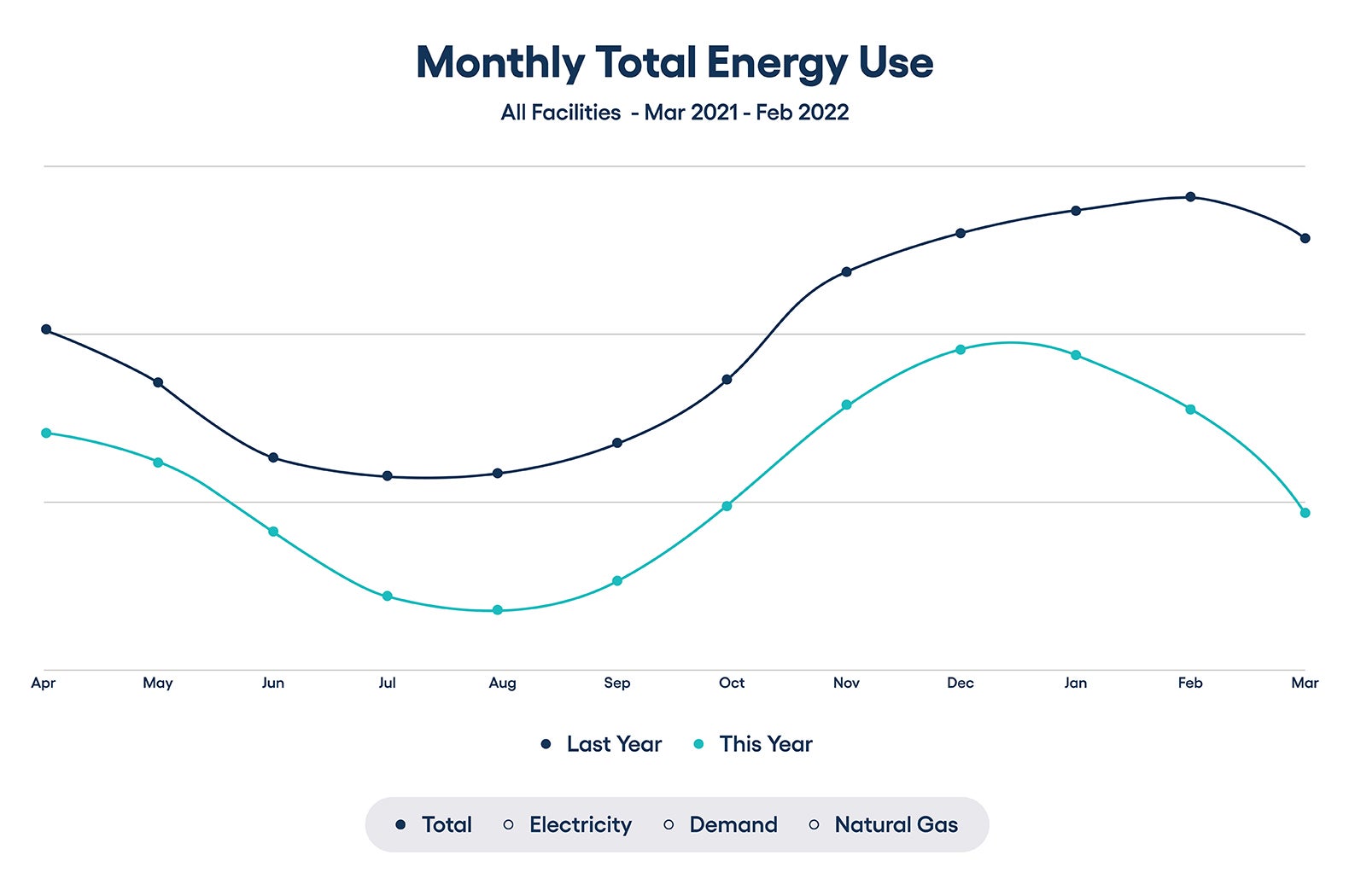

- EUI. Adopting a strategic asset management (SAM) technology platform with energy-tracking capabilities is the next place to look when it comes to sustainability efforts. SAM systems provide the capability to gather a baseline understanding of a building’s energy usage trends and identify high or inefficient areas of energy utilization.

The key focus areas for energy data tracking include the consumption of electricity, natural gas, water and possibly steam, if purchased from a third-party municipality. Additionally, a SAM system should monitor trends in weather exposure and occupancy rates as additional variables affecting consumption.

Recently, there has been an increased need to harden facilities against natural disasters, with many regions in the U.S. experiencing an uptick in flooding, storms, fires, droughts and more. If professionals aren’t aware of what assets they have and what baseline energy consumption looks like, it will be impossible to document and demonstrate the impacts of other major infrastructure changes.Simply put, using data to inform baseline operational levels before asset replacement is the only way to document and redefine the new normal for ongoing energy use intensity (EUI).

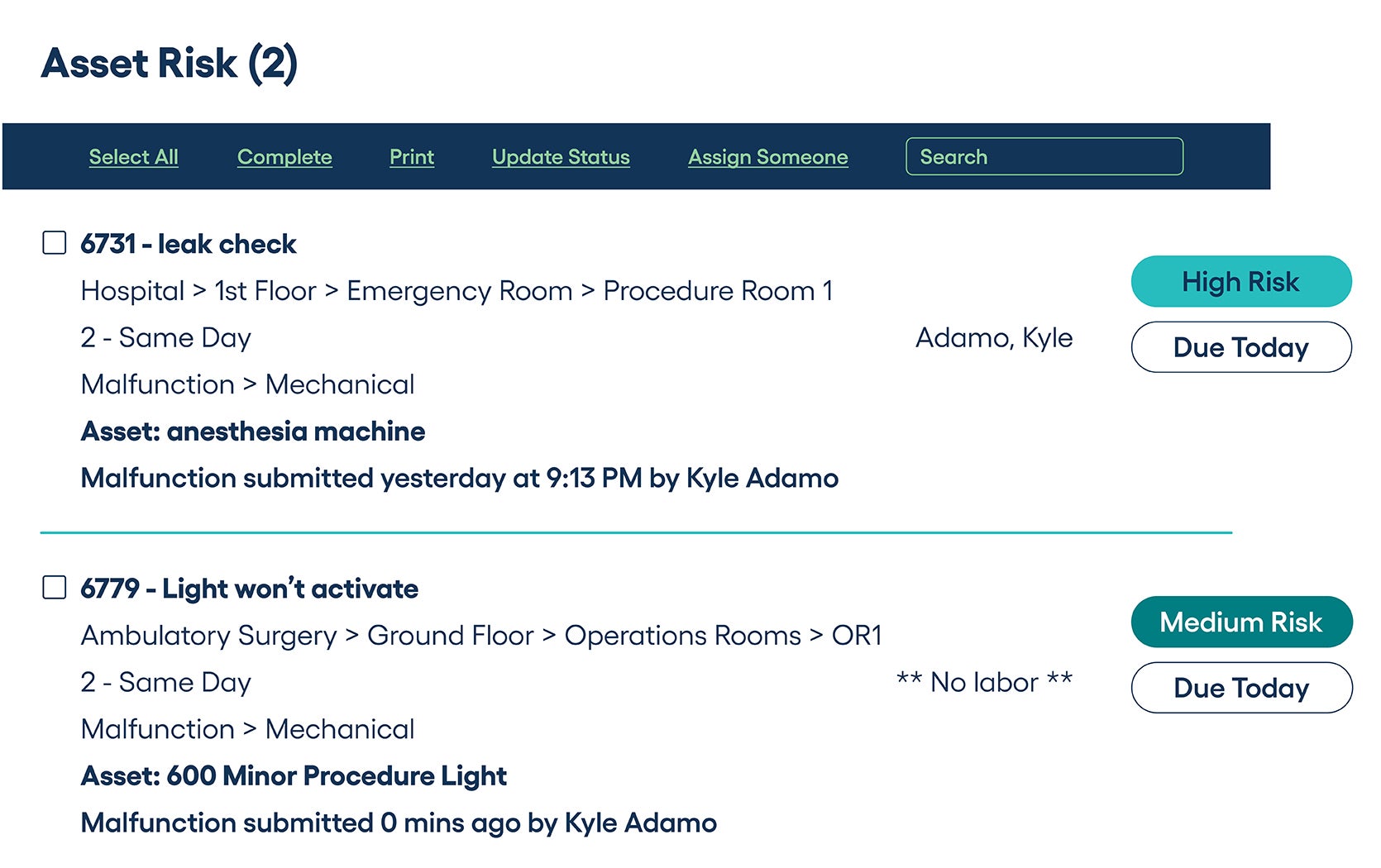

- Criticality and risk. As noted previously, understanding the criticality of an asset is important. Criticality and risk, in this context, is a measurement of how vital an asset is to facility operations, while the risk of an asset looks at the severity of impact if it were to fail.

Some assets are much more critical than others, so facilities professionals with limited resources must constantly prioritize which assets need replacement and when. Criticality and risk measurement impacts environmental sustainability because energy usage and carbon emissions are increasingly deemed critical variables in capital planning, with energy-intensive assets potentially impacting business performance, either positively or negatively.

For example, with more carbon tax legislation, facilities professionals will need to understand how much greenhouse gas emissions may be reduced by proper maintenance of existing boilers, or otherwise be able to identify when newer technologies and equipment may be required to achieve organizational goals.

Step 2: Take decisive action. With a baseline understanding of the health care facility as it is today, the next step is to prioritize and track the performance of those assets that are consuming the most time, energy and resources to operate and maintain. This again re-emphasizes the need for a continuous flow of data.

After a facility has put the proper technology and processes in place to monitor the KPIs, it is essential to identify usage patterns and develop action plans. These insights should serve as a guide for developing strategies that combat the bad actors of energy consumption and setting achievable and impactful sustainability goals. Why is this important? When armed with data, it is possible to deploy a rifle shot versus a shotgun approach to implementing process and asset improvement goals.

For example, a large nonacute educational organization on the West Coast experienced first-hand how impactful data is when it comes to energy savings by turning to technology to bring its energy cost avoidance from 28% to 50%. Tracking utility data as energy usage became important as it accounted for a third of the operational budget.

After analyzing energy usage from the building management system and comparing setpoints to occupancy trends and the local energy provider’s consumption data, opportunities for energy savings emerged in both HVAC and lighting controls. That organization now experiences more than 50% cost avoidance in energy savings and, over the span of 14 years, has saved millions of dollars in energy spending simply by optimizing the existing assets in the portfolio.

Acute and nonacute health care organizations, senior living and long-term care facilities and real estate managers alike can benefit in a similar fashion. On the surface, the facilities in each vertical enterprise serve very different purposes, but as all facility operators and owners are increasingly prioritizing environmental, social and governance projects, the methodology is the same.

In each case, decisions can be and are being made with an understanding that the long-term benefits of a sustainable facilities management plan will make for healthier and more sustainable organizations. Facilities professionals should pick an asset or a system, optimize it fully, then follow the data and pick the next optimization opportunity.

As with all aspects of health care, the health care facilities management community is heading into a technology renaissance where stronger connectivity driven by the Internet of Things (IoT) boom is becoming the new normal. Investments in IoT devices (e.g., asset submetering, and temperature, pressure and vibration sensors) are predicted to increase exponentially in the next five to 10 years, with no end in sight as to the ultimate possibilities of a fully integrated asset management program.

IoT ultimately describes and enables a streamlined, connected exchange of data between otherwise disparate systems, allowing the consolidation of information in one centralized location. What better way to sustain building operations and reduce environmental waste?

In daily practice, an IoT-powered system can improve and expedite more intelligent notifications directly to the maintenance staff. For example, if an HVAC system is not cooling properly, SAM software connected to an IoT asset sensor can alert the maintenance staff of a potential deficiency and provide an opportunity for corrective action, often before any human inputs can detect the issue.

This alarm-to-ticket-to-resolution value chain can lower energy waste stemming from a malfunctioning asset, potentially prevent a catastrophic failure and, in the best case, eliminate a failure node in the infrastructure that could potentially disrupt operations. Multiplied from one asset to many, this value chain represents the true definition of sustainability.

In health care, there will be continued movement away from legacy on-premise SAM installations, and investment in cloud-based solutions will continue to increase for both cost and security reasons. As an additional benefit, facilities professionals will see further integration and data-sharing capabilities across platforms that would otherwise be difficult or too costly to implement in a local data center.

Legacy enterprise systems with rigid architecture and installation requirements will be replaced by more agile solutions that are more adaptable to remote diagnostics, remote operating centers and third-party fault detection. As patient care and service lines are modified, this provides more flexibility for the facilities management team to adapt appropriately if installed assets can provide the necessary infrastructure performance or identify when they do not.

In that context, facilities professionals and technology providers alike will continuously be challenged to connect the dots from multiple data sources to validate and inform better infrastructure investment decisions.

Step 3: Communicate results and build upon success. As a health care organization embarks on the sustainability journey, communication is key — top to bottom, bottom to top and side to side. Open and transparent communication, with continued reinforcement of both goals and results, is critical for long-term success and enables the upward spiral of sustainability.

Each person on the team is a part of the sustainability journey, and sustainable practices require buy-in from everyone. At all levels of the organization, it is important to share the vision and engage staff in both problem identification and resolution to ensure everyone is on board with overarching sustainability goals. Some facility leaders have created sustainability teams within their organizations to help lead these efforts, which is a great start, but a best practice is to assume that the facility management and sustainability teams are one and the same and manage as such.

Continuous improvement mindset

Health facility sustainability, like many other visionary directions, is an effort without an endpoint.

It embodies sound design and initial construction but also requires a continuous improvement mindset and culture to meet or exceed the desired performance of the organization.

Facilities professionals must gather the data, take decisive action, communicate results and build upon success.

Asset management planning protects against obsolescence

Strategic asset management and advanced capital planning may seem like something only the largest and most sophisticated organizations can afford to do. But, increasingly, long-range capital budgeting for both acute care and senior living communities has become an essential strategy.

Conservative estimates suggest, as a national average, up to 47% of major mechanical, electrical and plumbing assets in service today have exceeded expected useful life. Every facility is unique and has its own challenges and opportunities, but as averages go, many individual sites can have an even larger accumulation of aging infrastructure, depending on past investment strategies or a lack thereof.

It’s called deferred maintenance. And if deferred maintenance levels grow too large, it can become almost impossible to recover the facility without major, disruptive construction and renovation.

In any case, if facilities professionals and executives don’t plan for upgrades and replacements, surprise bills can suddenly mean the difference between sustainability and barely scraping by. By documenting and tracking deferred maintenance levels, it is possible to proactively manage capital equipment expenses and effectively plan for asset obsolescence.

Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a shift toward telehealth and remote care. With the proliferation of outpatient clinics and ambulatory service centers, hospitals are primarily handling acute cases that require more advanced care. However, from an infrastructure standpoint, hospitals built decades ago may not be able to transfer to these more acute service lines without significant investment. Because that investment requires engineering analysis to repurpose spaces, asset replacement can only be managed proactively. Running assets to failure is no longer an option.

The health care field has recently seen many challenges, but it should not get in the way of forecasting a more efficient and cost-effective future. The hospital facility itself is a clinical asset, so digging into the data, and learning, adapting and modifying the understanding of infrastructure investment needs will allow any health care organization to create an asset management and capital plan with obvious benefits for years to come.

About this article

This article is part of an exchange agreement between the American Society for Health Care Engineering and the International Facility Management Association, which ran an earlier version in its Facility Management Journal.

Mark Mochel, CHFM, PMP, ACABE, is strategic account executive, and Dan Arant, CEM, PEM, is manager for energy and environmental, social and governance in North America at Brightly, a Siemens company. They can be reached at mark.mochel@brightlysoftware.com and dan.arant@brightlysoftware.com.