Stressing science

The next five years will be a transformative era in health care. Care delivery is expected to become much more integrated and efficient. Evidence-based processes — from surgery to the way hospitals are cleaned — will expand greatly.

The next five years will be a transformative era in health care. Care delivery is expected to become much more integrated and efficient. Evidence-based processes — from surgery to the way hospitals are cleaned — will expand greatly.

During this time, hospitals must prove they can operate profitably on today's Medicare-level reimbursements or below. Likewise, hospitals must capture incentives and avoid costly penalties initiated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to spur greater progress on reducing health care-associated infections (HAIs) and readmissions.

In this shifting landscape, infection prevention and environmental services (ES) teams almost certainly will have to do more with similar or fewer resources. And with the Affordable Care Act extending coverage to 32 million more Americans over the next decade, it could become more challenging to reduce costly HAIs.

"My No. 1 concern is budgets," says John Scherberger, CHESP, R.E.H., president of Healthcare Risk Mitigation Inc., a South Carolina-based consulting firm that helps hospitals to reduce health care- and community-associated infections. Scherberger is worried because many ES and infection control departments have lost staff due to organizational belt tightening.

Ironically, this comes at a time when studies have shown that hospitals have made progress in reducing some HAIs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) last year, for example, reported significant decreases in 2010 for:

- Central line-associated bloodstream infections, 33 percent;

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections, 18 percent;

- Surgical-site infections, 10 percent;

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections, 7 percent.

Challenges loom

Similar progress has not been made on Clostridium difficile rates and Norovirus outbreaks. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality projects that C. difficile rates will rise from an average of 11.6 cases per 1,000 hospitalizations in 2008 to 12.4 per 1,000 hospitalizations in 2011. Meanwhile, Norovirus was responsible for 18.2 percent of all infection outbreaks and 65 percent of ward closures during a two-year period, according to a study published last January in the American Journal of Infection Control.

With C. diff infections alone resulting in at least $1 billion in health costs annually according to the CDC, and CMS no longer reimbursing for HAIs, hospitals can't afford to see this pattern continue. To combat these stubbornly persisting pathogens, ES and infection prevention teams will have to increase collaboration and focus on environmental factors in disease transmission.

More than a surface issue

William A. Rutala, Ph.D., director of the hospital epidemiology, occupational health and safety program at the University of North Carolina hospitals, notes that environmental contamination remains an underappreciated link in the spread of pathogens from caregivers to patients. Speaking at the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE) conference in September, Rutala said about 20 percent of HAIs are linked to the environment.

William A. Rutala, Ph.D., director of the hospital epidemiology, occupational health and safety program at the University of North Carolina hospitals, notes that environmental contamination remains an underappreciated link in the spread of pathogens from caregivers to patients. Speaking at the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE) conference in September, Rutala said about 20 percent of HAIs are linked to the environment.

This makes the role of environmental cleaning and disinfection essential in reducing disease transmission risks. A study published in the October issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology underscores this point.

Researchers from the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center conducted a randomized trial comparing regular cleaning protocols of housekeeping staff with daily disinfection of high-touch surfaces performed by researchers (i.e., bed rail, bedside tables, call button, phone, toilet seat and bathroom hand rail) in 34 C. diff and 36 MRSA isolation rooms.

The study assessed hand contamination of physicians, nurses and research staff six to eight hours after disinfection procedures. In rooms with daily disinfection, there were significant reductions in the amount and frequency of pathogens on the hands of investigators and health care personnel caring for the patients (6.4 percent with daily disinfection vs. 30 percent with standard cleaning).

"These findings add to the growing body of evidence supporting environmental cleaning and disinfection as an important infection control strategy," said Sirisha Kundrapu, M.D., lead author of the study.

This assumes, of course, that room cleaning and disinfection processes are thorough. That's not always the case, as many studies have shown. Research by Philip C. Carling, M.D., and other researchers, for instance, have shown that about two-thirds of health care surfaces still contain pathogens even after cleaning, Rutala noted in his AHE lecture. Rutala added that ES leaders will need to educate hospital leaders about the tools, time and people they need to ensure that room surfaces are cleaned thoroughly.

Part of making that case to senior leadership could come from sharing data on the monitoring of surface-cleaning practices. Fluorescent marking and adenosine triphosphate systems can help ES team leaders evaluate whether high-touch objects and surfaces in patient rooms and bathrooms are processed thoroughly. A growing number of hospitals have begun to deploy these tools, but many still do not use them.

Verifying cleaning thoroughness will become increasingly important, Scherberger notes, because the findings can provide valuable teaching and training lessons. He adds that ES and infection prevention leaders need to help hospital executives see the parallels of these efforts with clinical safety initiatives.

"What we have been doing in environmental services is a clinical process. It's no different from removing microbes from an injection site or a surgical preparation site. We're just doing it on a larger scale," Scherberger says.

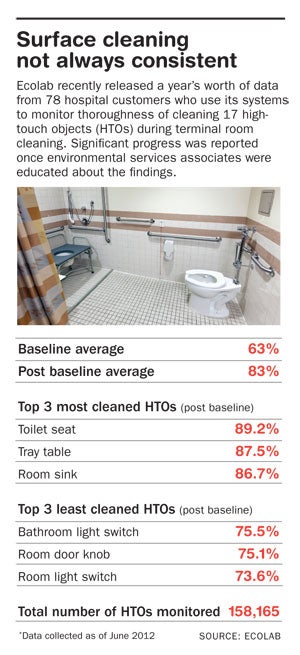

Minnesota-based Ecolab Inc. is using data from some of its health care clients to develop a database on cleaning performance. The company in October released 12 months of data from 78 hospitals that use its EnCompass monitoring and DAZO fluorescent gel marking systems.

Baseline data showed that 63 percent of 17 high-touch objects from the CDC's environmental checklist for monitoring terminal room cleaning were thoroughly cleaned. A year later, thanks to ongoing training and feedback to ES associates based on the EnCompass data, that percentage jumped to 83 percent. In all, more than 158,000 total objects were measured for cleaning thoroughness, including toilet seats, tray tables, room sinks and bathroom light switches.

While initial findings focused on data from patient rooms, Linda Homan, R.N., CIC, Ecolab's senior manager of clinical and professional service, envisions the program having a wider impact.

"We're extending this beyond patient rooms. We have modules for intensive care units (ICUs), emergency departments, clinics and operating rooms (ORs). Each has different high-touch objects and different areas of focus. We'll be able to benchmark the data, feed it back to users and help them drive improvement to their hospitals," Homan says.

High-tech options

Other infection prevention technologies that are likely to get greater consideration include ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide vapor room decontamination systems. These units can be placed in ORs, ICUs, isolation rooms and other locations after routine room processing is performed. The systems then kill residual bacteria left on surfaces. UV germicidal irradiation also has been used successfully in heating, ventilation and air conditioning

Many UV light and hydrogen peroxide vapor systems might be viewed by hospitals as expensive, but their potential to prevent serious infection outbreaks makes them hard to ignore. Manufacturers are quick to point out that avoiding even a couple of serious infection outbreaks could pay for the units. Nonetheless, ES teams need to determine how often and where the technologies can be used routinely and how they will impact workflow practices.

Some facilities have documented significant reductions in various infection rates after using a UV pulsed-light disinfection technology from Texas-based Xenex. A number of other UV light manufacturers also have targeted health care, and proliferation of this technology likely will continue. Various studies also have shown the efficacy of hydrogen peroxide vapor systems in room decontamination.

Scherberger is unconvinced hospitals today can afford to routinely deploy UV light and hydrogen peroxide vapor systems throughout facilities. The time it takes to use these units would add to room turnaround times if deployed universally, he says. Still, he sees strong potential for their applications.

"In the next five years and beyond I believe that they can be a great adjunct to environmental services. But they have to be used in appropriate areas such as terminal cleaning of operating rooms or dialysis units at the end of the day," Scherberger says.

The University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics last December leased a Xenex UV pulsed-light disinfection system to help reduce health care-associated C. diff. Tom Peck, director of environmental services, says the system initially was used in the pulmonary and cardiothoracic surgery units. Since deploying the room disinfection system 100 percent of the time in these units where patients often are immunocompromised, Peck notes that the cardiothoracic unit had no C. diff infections during the first four months. The pulmonary unit saw a sharp decrease in C. diff rates as well.

Not all armamentaria in the infection prevention fight of the future will be so sophisticated. In fact, Scherberger says simple steps like replacing cotton cloths with microfiber products can improve results significantly in removing bioburden from surfaces. He also sees a continued emphasis on developing cleaning agents and disinfectants that kill bacteria and spores in a minute or less.

Bob Kehoe is associate publisher of Health Facilities Management.