Baby watch

According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, between 1983 and 2010, 47 percent of all infant abductions were from health care facilities. These abductions not only were from nurseries, but also from pediatrics wards and other locations on premises, including a staggering 58 percent from the mothers' own rooms.

According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, between 1983 and 2010, 47 percent of all infant abductions were from health care facilities. These abductions not only were from nurseries, but also from pediatrics wards and other locations on premises, including a staggering 58 percent from the mothers' own rooms.

The electronic security systems industry has devised innovative solutions to help nurses, health care security administrators, law-enforcement officials and families protect these most precious and vulnerable patients.

Many modern hospitals have state-of-the-art, electronic infant-security systems that link specialized infant bracelets equipped with radio frequency identification (RFID) tags with similar tags issued to the mother to ensure she has the correct child. These tags then connect to a wireless perimeter system that sounds an audible alarm and flashes a warning on the nurse's screen when an infant is taken out of designated areas. At the same time, the security system automatically disables elevators and exits.

Making certain the facility's infant-security system is operational and providing the intended level of protection is critical to the hospital's overall security plan. A good way to do this is through a product-neutral evaluation of the system, policies and procedures.

Whether a consultant or internal facilities staff handles troubleshooting and maintenance issues for the system, completing the basic inspection and testing processes can help analyze problems and keep the system online and working properly.

Inspecting the system

At set-up, health facility professionals should request an installation manual from the manufacturer or installer to keep on hand in case problems arise. Having the installation manual will allow facility professionals to complete a thorough inspection of the equipment and its operational parameters.

The first task in analyzing an infant-security system is physically inspecting the system to make sure that the equipment has been installed correctly. This includes the following steps:

Conduct a visual inspection. Equipment should be inspected for obvious damage, such as cracks in the body housings and missing antennas.

Verify secure equipment mounting. All equipment must be securely mounted and not mounted to a surface that could cause interference, such as metal studs, ductwork or metal door headers.

Check wire terminations. The wire terminations should be examined for loose screws or other signs of loose connections. It is common for cables to be pulled or wrapped up with other cables during the installation of equipment. This can lead to the cable's being pulled loose from the termination block or some of the wire strands being damaged.

|

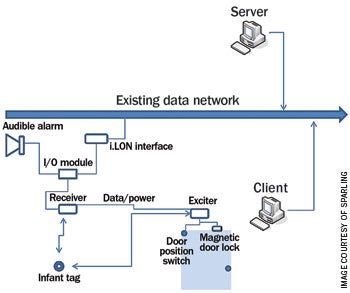

| A common network topology for an infant-protection system |

Often, termination issues can be resolved easily by cutting, re-stripping and re-terminating the cable. If the cable has been pulled tightly and is too short for re-termination, you may be required to install a splice point and extend the cable to fit.

Another common problem is when the cable has not been stripped back properly, causing a portion of the cable jacket to be caught under the termination block.

Check the condition of the cable. Damaged cable can have a direct effect on the amount of power being delivered to the equipment and the amount of attenuation in the communications pair of the cable. As the system and infrastructure begins to age, the original cable can deplete, causing power and data alarms and potential failures. Regular cable diagnostics can help alleviate this situation.

Inspect the power output. As part of the physical infrastructure inspection, examination of the power output is critical to system performance and operation. In many instances, power and communications for infant-protection equipment is wired together in a daisy-chain configuration and has limitations on the number of devices per leg. If the voltage is low at the power supply itself or at a leg of the power distribution, the power supply may be faulty and need to be replaced. If the output power meets the manufacturer's specification, each device in the chain should be tested to verify adequate power is being delivered to all devices.

Test data transmission to the system. The length of the equipment leg can be an issue for systems that have been expanded by one or two devices. Sometimes installers will add devices to the end of a systems leg that is already at its limit. If too many devices are installed in a given leg in a serial installation, such data errors as propagation delay or low power can occur. Facility professionals should reference the installation manual for information on power and attenuation requirements and number of devices permitted on a leg.

Verify Internet protocol (IP) communication. As more and more systems are becoming IP network-based, the communication between the devices and server controller is handled by a traditional local area network (LAN) configuration and topology. To verify communication of IP-based equipment, facility professionals may use a Ping utility command to help determine data protocol communication problems and simplify the troubleshooting process.

As the industry moves to a true IP star topology for infant-protection systems, each device will have its own IP address and will be "home run" to the head end. This will add reliability and ease of use and maintenance.

Checking system operation

There are three common types of alarms that signal a possible abduction. Running a report of the alarms helps to find potential issues with the system and possible false alarms in an infant-protection system. These alarms are:

Tag-off-body alarm. This indicates that the identification device is not touching the skin. Each manufacturer's tag works a little differently. Some tags require constant contact with the skin and some only occasional contact with the skin before sending an alarm. If a tag-off-body alarm report shows consistent false alarms, some potential remedies include:

- Inspecting the tags for defects and wear and tear;

- Reviewing operational procedures with the clinical staff to ensure proper application on the patient.

Supervision time-out alarm. This indicates that the RFID tag is not being read by the system or that there is a lapse in radio frequency (RF) coverage in the area that may require the addition of more receivers to the system. If this alarm is tripped falsely at a regular rate, running either a wireless coverage analysis or a walk test can help identify problem areas.

Portal alarm. This indicates that someone has gone through a door with a child who is wearing a monitoring device. If these alarms are common on the report, there could be a door that is not closing properly or a door with a damaged switch that needs to be replaced. This is easily remedied by a physical inspection of the egress systems.

Testing wireless coverage

In an initial system layout, items often are not taken into account that could affect the RF signals in the area. Some of the physical causes of RF interference in hospitals are HVAC ductwork, magnetic resonance imaging rooms, and metal mesh in walls and elevator shafts.

Infant-protection systems use specific frequencies in various RF bands, often in the 200-megahertz range, and require a tester that is supplied by the manufacturer or installer to run diagnostic tests.

If a tester is unavailable, a tag can be signed in and activated to test the system in a manual configuration, also known as a walk test. This requires one person to walk the tested area with an active tag, and another person to be at the master station to watch and listen for alarms and the tag location display. At the same time, the tag holder will check to see if all exit locations are being locked down within the prescribed parameters of the system.

Using a walk test also allows for other hospital staff and end users to see and hear the system and learn what to expect in the case of alarms.

Assessing communications

Many infant-security systems are network-based and rely on the health care organization's existing enterprise for communications to the servers.

This has allowed for lower installation costs and the ability to access the security system from the network. However, this also means that a main design consideration needs to be network uptime and the acceptable risk of downtime.

|

| LEFT: Placing monitoring equipment at nurses' stations allows staff to perform multiple tasks while keeping tabs on the infant-protection system. RIGHT: Careful layout and design of an infant-protectino system is critical to ensuring there are no dead areas in coverage, including the NICU spaces. |

Because an infant-security system has no acceptable downtime, the system may need to be installed on a separate network that has access to the main network, but remains fully functional during a network outage. Although this does not eliminate the possibility of network loss, it reduces the possibility of interruption of service due to the primary data network's being brought down. In this configuration, facility professionals still would have an interface to the hospital's primary network; however, it would be in a virtual LAN (V-LAN) configuration and would not be dependent on the primary network for operation.

In any network configuration, availability and redundancy are critical. This is accomplished by redundant power supplies, emergency power and uninterruptible power-supply systems in each communication room where the head end of the infant-protection system is located.

Evaluate organizational policies

Organizationally, policies and procedures should make it clear to users how the alarms are to be answered, who is responsible for testing the system, what training programs need to be supported, and what procedures should be followed if the system goes down.

Multiple operational departments should be engaged in the system's management. These include staff in the following areas:

Security. The security department helps to administer the system and determine how the obstetrics and neonatal intensive care staff receives and responds to the different alarms.

Information technology (IT). This department is responsible for the networking aspects of the system and how it relates to the other systems through a converged network. IT support also must determine fail-safe methods that need to be in place in case the network goes down and to handle system upgrades.

Facilities. As with any technology system, basic troubleshooting and regularly scheduled maintenance are paramount. The facilities department should conduct testing and routine maintenance on a quarterly basis.

Clinical and security. Training for clinical and security staff is a necessity. A hands-on class on the operational system is the only way to make sure health care employees understand their own system.

Two levels of training also are needed, one for administrators and one for users, because different skill sets are involved. Obviously, new staff must be trained as part of their orientation; but existing staff will need training when upgrades affect the system's operation. Periodic refresher courses also are helpful. Training keeps clinical staff aware of potential conditions and helps minimize false alarms.

Implementing regular infant-abduction drills is a way to help find deficiencies in equipment, training, policies or procedures. The Joint Commission does not require infant-abduction drills, so it is up to the organization to determine the appropriate actions to ensure successful implementation of the procedures. Because regular fire drills are mandatory, implementing the infant-abduction drill at the same time makes sense.

It is important for hospitals to understand that a fully functioning electronic infant-protection system is only a part of the security plan for protecting infants.

There should be check-in and check-out points upon entering and exiting the secure floors to verify who is on the floor and why. All staff need to be trained to know what to look for in these secure surroundings, such as new employees working in the area or suspicious behavior by visitors.

Critical component

Infant-protection systems are critical components to hospital-security systems and policies. They need to be maintained, operated and monitored according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

Like any complex technology, the infant-protection system is only as good as the users who operate it and the technicians who maintain it. If used properly, however, it can be a valuable tool for the health care provider and, more importantly, a life-saving device.

Scott McChesney is an electronic security systems consultant and Tod Moore, RCDD, CSI, CDCD, is principal and IT architecture practice leader for Sparling, Seattle. They are at smcchesney@sparling.com and tomoore@sparling.com.

| Sidebar - Matching security technology with proper employee policies |

| Today's infant-protection systems are sophisticated and powerful, but only when there are policies, procedures and maintenance schedules in place to keep them operating properly. When evaluating the needs of the hospital, the system designer should meet with the various stakeholders of the facility, including nurses, doctors, administrators, security directors, and facilities and information technology personnel. A typical design session begins with a discussion on operational requirements and the physical layout as well as research into crime data for the local area. This is followed up by demonstrations and technical explanations of the systems, which often cause one or more of the participants' eyes to glaze over. But as the fog clears and the impact of the system and the benefits to the patients and staff are realized, the team usually is on board and ready to go. Unfortunately, after the systems are installed and time passes, the various departments involved in the initial visioning and design sessions move on to other projects or other departments within the organization. Before long, the obstetrics department and the neonatal intensive care unit, which are directly affected by the infant-security system, are left with little or no support to make sure that the system is operating properly and providing the intended level of protection. Often, infant-security systems that were installed, tested and working correctly at the outset are left with little or no maintenance, no training for new staff and no ongoing training for the existing staff. Without the appropriate personnel involved to assure that the hospital's policies are being followed and that the staff is properly trained, the "boy who cried wolf" scenario can play out after numerous erroneous alarms are triggered, causing staff to start ignoring alarms just as one ignores a car alarm in a mall parking lot. These false alarms can be caused by several conditions, including the following:

In some instances, nursing units have put their whole system on mute so it won't continually bother them with false alarms, defeating the purpose of the system and substantially increasing the safety risk. One nurse said that her department simply didn't use the system because no one knew how it worked and it was a nuisance — a horrible fate for such a powerful technology. Health care organizations that have electronic, infant-security systems in place have a powerful tool to protect their patients. However, if the system is not working properly due to insufficient policies and procedures, neglectful maintenance or limited staff training, the health facility could have a false sense of security that puts it at greater risk for infant-abduction incidents. |