A closer examination of regulatory waivers

Survey challenges may be frustrating, but they also push facilities managers to think creatively and refine their approach.

Image by Getty Images

Experienced health care facilities managers know the drill — the survey ends, and suddenly, they’re staring at a report that has a list of issues they must address.

Whether the facilities manager has been there before or this is their very first survey, they should take a deep breath and give themselves some credit. Surveys can be overwhelming, and navigating compliance is no small feat. But they’re here, doing the work, and that deserves recognition. Being a facilities manager requires resilience and resourcefulness — qualities they undoubtedly possess.

Now, it’s time to tackle the survey report. Some deficiencies are low-hanging fruit that, while requiring attention, can be resolved with a bit of time and effort. Others demand more complex solutions, requiring collaboration with other departments, external resources or even the allocation of capital funds that haven’t been planned for. But what happens when facilities are cited for non-compliance on an issue that seems impossible to correct? What do managers do when standard fixes won’t cut it?

Some physical environment deficiencies can feel utterly defeating, like a reason to throw in the towel, walk away and never look back. Deficiencies such as a high-rise health care occupancy building that isn’t fully sprinklered after the deadline, travel distances exceeding the limits, structures that fail to meet their designated construction type, vertical shafts that aren’t fire-rated correctly, projects demanding significant capital investments when funds simply aren’t available or costly improvements to buildings already on the chopping block can make compliance seem impossible.

But before facilities managers give up, there’s another path they should consider — one that many discuss but few fully understand: alternative compliance strategies, commonly referred to as “waivers.” These approaches may offer solutions when traditional fixes aren’t feasible, giving facilities managers a way forward even in the toughest situations. In cases like these, it’s not just about working harder — it’s about working smarter.

The following section explores the next steps for handling those tough compliance challenges.

Why this matters

Before diving too deep, one should first consider why an organization’s leaders are concerned about those deficiencies on that survey report. Hint: one big reason is money. That sounds callous, but it’s not. Facilities managers like to remind themselves that everything they do is for the patient, and there is no doubt about it. In the words of William James Mayo, M.D., a founder of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., “The needs of the patient come first.” However, without money, hospitals would be forced to close, and that is certainly not good for patients or communities.

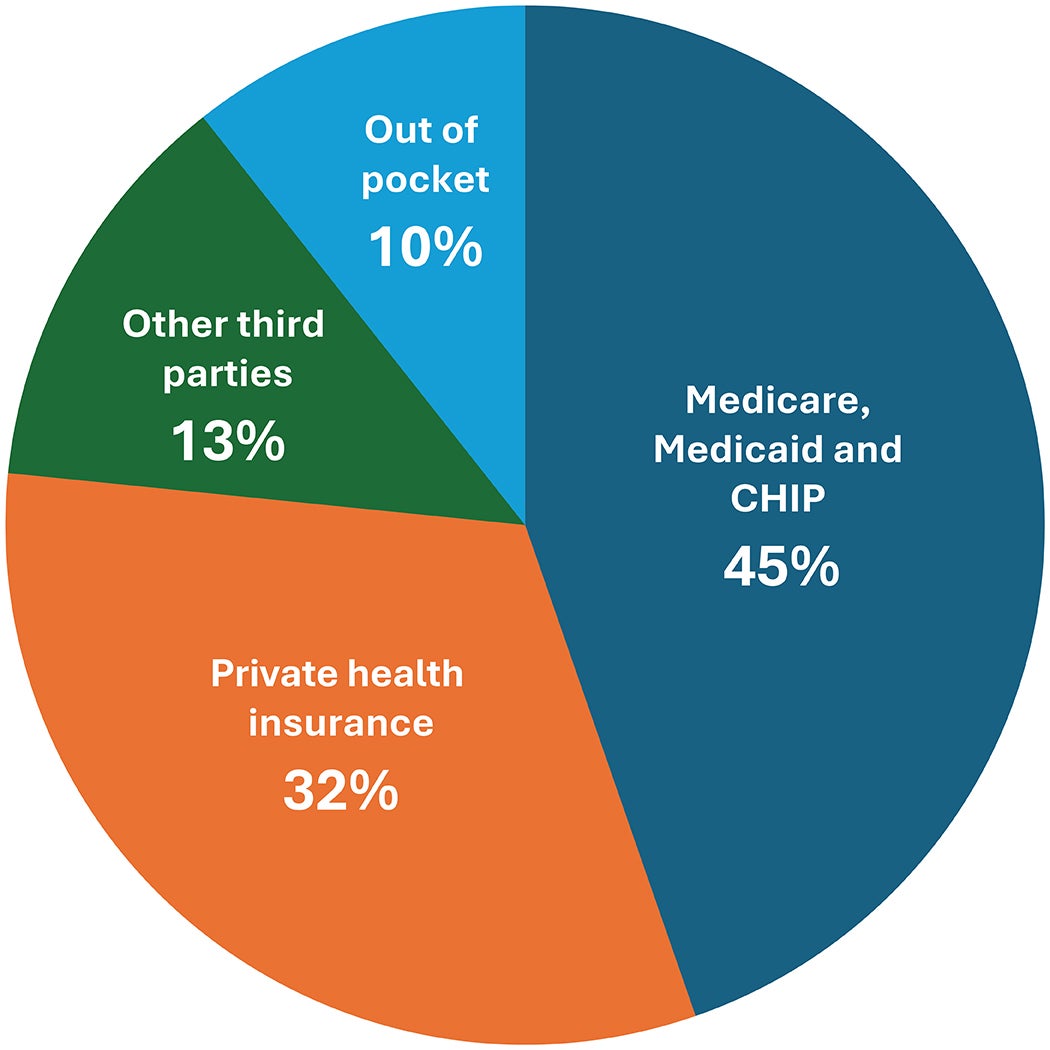

There are a handful of parties (see graphic on right) that pay for most of the health care services in the United States. The biggest is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). It is estimated that CMS accounts for roughly 45% of health care spending through Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Private health insurance pays about 32%, other third parties pay about 13%, and out-of-pocket costs are about 10%.

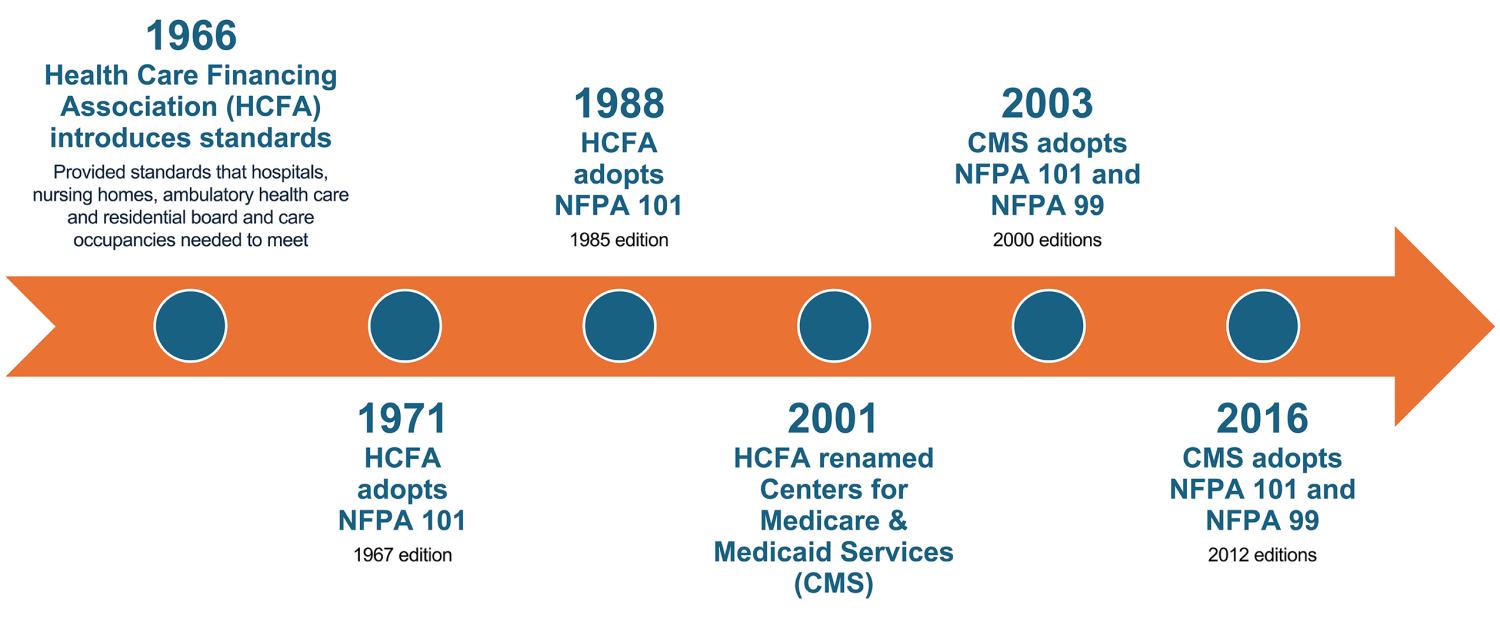

Because CMS is the biggest payer, it has leverage to make the rules for any hospital participating in its programs. It does this through the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) rules that an organization must comply with to get funding. Through the CoPs, CMS has adopted the 2012 editions of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code® , and NFPA 99, Health Care Facility Code. That is why facilities focus so much on these two documents in health care compliance. The CoPs also require that any identified deficiencies be included in a Plan of Correction, which is normally 60 days.

What should facilities managers do in the case of a deficiency for which they can’t comply? Sometimes facilities managers need more time, and sometimes they encounter deficiencies that are all but impossible to correct.

Luckily, the CoPs offer some reprieve. If a hospital faces significant challenges in meeting Life Safety Code requirements, a waiver may be granted. This can happen if a state agency (SA) or accrediting organization (AO) makes the recommendation, and the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services determines that following the rules would create an unreasonable hardship. However, a waiver is approved only if it does not put patients’ health and safety at risk.

Similarly, if complying with the Health Care Facilities Code or any of the reference publications of the Life Safety Code and Health Care Facilities Code would be too difficult for a hospital, CMS has the authority to waive specific provisions — as long as patient safety remains unaffected. But getting this approval from CMS can be difficult.

Exploring equivalencies

In this era of doing more with less, it’s good for facilities managers to first investigate whether they even need to correct the issue. If the issue is a Life Safety Code deficiency, the organization may be able to prove compliance through an alternative method. The 2010 edition of NFPA 101A, Guide on Alternative Approaches to Life Safety, is referenced from the Life Safety Code. NFPA 101A offers a method to demonstrate that the facility, while not meeting all the requirements of the Life Safety Code, provides an equivalent level of protection. This is accomplished using a series of worksheets called the Fire Safety Evaluation System (FSES). A tool that guides users through these worksheets may be accessed at ASHE's website.

There are different chapters in NFPA 101A for different facility types. For example, Chapter 4 is for health care occupancies, and Chapter 7 is for board and care occupancies. If facilities managers have multiple occupancies in the same building, CMS has traditionally required that facilities use the chapter that applies to the primary occupancy for the whole building. For example, if a zone of the hospital building is a business occupancy, managers must use the Health Care Occupancy Worksheets found in Chapter 4 for that zone, not the business occupancy worksheets found in Chapter 8.

Each chapter offers a guide on how to fill out the worksheets for each zone of the building. (A zone is defined as a fire or smoke zone, which are compartments divided by either a horizontal exit or a smoke barrier). For a facility to be determined to be equivalent, all the zones must achieve a passing score on the FSES worksheets, found at the end of each chapter.

CMS has stated in a memo that “the FSES can be completed by the facility, a trained consultant or by the SA at their discretion.” Generally, whoever completes it needs to have a good knowledge of the Life Safety Code, the various life safety features within the zone and the building overall.

If an organization is accredited, the first step in gaining approval for an equivalency is to submit the documentation to the AO. Each AO has its own process, so it’s best to first reach out to them to find out how to submit the documentation. If a facility is not accredited but participates in CMS programs, a similar process takes place but with the SA as the initial reviewer.

Getting approval by the AO or SA is not enough for an organization that participates in Medicare and Medicaid; CMS also must approve the equivalency and grant what they refer to as a “continuing waiver.” Once the AO or SA has approved the documentation, they will facilitate sending it to CMS for its approval.

For facilities that do not participate in Medicare or Medicaid but still are accredited, such as many Veterans Health Administration or Department of Defense facilities, this process ends with approval from the AO.

Even if managers show equivalency and are granted a continuing waiver by CMS, they will be expected to repeat the process with every survey. Facilities managers know how much health care facilities are in a constant state of change. Modifications, additions and remodels all impact the overall life safety of the facility. By going through the exercise of completing the FSES worksheets every three years, managers will be able to demonstrate whether the facility still meets an equivalent level of safety to the Life Safety Code.

The FSES worksheets evaluate each zone based on several criteria — containment safety, extinguishment safety, people movement safety and general safety. Managers must achieve a passing score in each of these categories to be considered equivalent. Sometimes in the process of filling out the FSES worksheets for each zone, facilities managers find that some zones can’t achieve a passing score in these categories even after they’ve corrected all the other life safety deficiencies on their survey report. There are a few methods that allow facilities managers to gain additional points to receive a passing score.

Figuring out these mitigation strategies requires managers to go back through the FSES worksheets, noting the areas where there is room for improvement. For example, if managers are short in the containment safety category, they could potentially add closers to the corridor doors or add sprinklers in the corridors and habitable spaces. Each of these actions would gain points in the rating system that could take the facility out of the negative, so facilities managers must get creative in thinking of ways they could achieve this.

In addition to verifying positive ratings in each of the four categories mentioned above, facilities managers must verify whether a list of items included in the Facility Fire Safety Requirements Worksheet are met. Even if some on the list are not met, it is still possible to achieve equivalency, but it may require some convincing by the facilities manager. The authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) needs to make sure that these items have been evaluated and mitigated to the satisfaction of the AHJ.

It should be noted that equivalency can only be proven using this method for a Life Safety Code deficiency and doesn’t apply to Health Care Facilities Code deficiencies. Unfortunately, there is no NFPA 101A-equivalent document that applies to Health Care Facilities Code deficiencies. For these deficiencies, NFPA 99 does allow for equivalencies (Section 1.4), but getting approval from CMS has traditionally been more challenging.

Other LSC/HCFC waivers

If health care facilities managers can’t prove equivalency, they’ll need to correct the deficiency, but they can apply for a waiver to give their organization more time to make needed corrections. As noted on the CMS website, “CMS may waive for periods deemed appropriate specific provisions of the [Life Safety Code] and [Health Care Facilities Code] which would result in unreasonable hardship upon a facility, but only if the waiver will not adversely affect the health and safety of the patients or residents.”

The AOs take a similar approach for hospitals that do not participate in Medicare or Medicaid. Sometimes, they use some different terminology. For example, The Joint Commission calls these “time-limited waivers.” Regardless of the terms used, these waivers are meant to be temporary in nature.

For organizations that are accredited, applying for a Life Safety Code/Health Care Facilities Code waiver is like getting approval for an equivalency in that the AO or SA must first review and approve the application before sending it to CMS for approval.

For these waivers, the organization must prove that the health and safety of the patients or residents is not adversely affected. As one can imagine, this can become somewhat of an exercise in persuasion. The best way to show that there are no adverse effects is to implement Alternative Life Safety Measures, also referred to as Interim Life Safety Measures.

Regarding categorical waivers. Facilities managers also may have heard of categorical waivers. Categorical waivers are rarely used anymore, but they used to be a lot more popular. For example, before CMS adopted the 2012 Life Safety Code and was using the 2000 edition instead, it recognized that some of the provisions in the later editions would be beneficial for facilities to be able to utilize. So, they issued a categorical waiver that applied to all facilities under their jurisdiction.

These waivers now are rare, but there are still categorical waivers in effect for things like humidity levels in anesthetizing locations, such as operating rooms, and for allowing microgrid electrical systems as a means of emergency power.

Regarding 1135 waivers. Sometimes, deficiencies are completely beyond a facilities manager’s control — events like natural disasters or pandemics can throw everything out of compliance. When that happens, they may be able to apply for an 1135 waiver, which is allowed during a public health emergency.

Under the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, the U.S. president can declare a major disaster or emergency if the situation overwhelms state and local governments or if a governor requests federal assistance. These declarations enable the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to temporarily modify or waive certain requirements. The goal is to ensure that people with Medicare and Medicaid continue to have access to care, even in a crisis.

If managers need guidance on applying for an 1135 waiver, the CMS waivers and flexibilities website has plenty of helpful resources, including documents and videos to walk facilities managers through the process.

Tackling the survey

After reading this article, health care facilities managers hopefully are feeling a little more confident about tackling that next survey report.

There are multiple ways to address these challenges without exhausting time and resources — managers just need to approach the solutions strategically. They also should keep in mind that they have only 60 days to develop their plan of correction for any deficiencies, so if they intend to apply for a waiver (whether it’s an equivalency or a temporary Life Safety Code/Health Care Facilities Code waiver), they’ll need to start the process immediately.

If facilities managers have a follow-up survey, their surveyor will need to see clear action on any condition-level deficiencies — even if that action is applying for a waiver. Managers should be sure to keep thorough documentation of their application readily available.

These survey challenges may be frustrating, but they also push health care facilities managers to think creatively and refine their approach. Health care facilities managers should stay focused, rely on their knowledge and take decisive action. Their hard work will pay off, hospital leadership will be pleased with their resourcefulness, and their patients will be safe. At the end of the day, that is what is most important.

Related article // Some examples of appropriate applications of code waivers

This sidebar article walks health care facilities managers through some examples of when it might be appropriate to apply for a waiver for the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, and NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code.

- If a facility has a smoke compartment that is too big on a floor that the facility masterplan shows will be completely gutted and remodeled in the next year or so, it would not make sense to relocate the smoke barriers for that short amount of time. A manager could apply for a waiver and show that the patients on that floor would not be adversely affected by providing some additional safeguards. These could be as simple as staff education and training, or it could be more complex, such as providing additional firefighting equipment in the area.

- If a facility has a Category 1 medical gas system, but the alarm function on one of the local alarm panels is not working properly and parts are on backorder to fix it, a waiver could potentially be used on a temporary basis. The manager would have to show how they are mitigating the problem, perhaps by working out a method of communication between staff in that area and staff monitoring the master alarm panel.

- If an emergency standby generator is undergoing replacement, and the facility doesn’t have other generators serving the areas affected, managers could apply for a waiver. The method of mitigation could be to bring in a portable generator on a temporary basis. In this situation, it’s important to remember that all the required inspection, testing and maintenance for the permanently installed generator would have to be completed on the temporary replacement.

Mitigation strategies, such as Alternative Life Safety Measures (ALSMs), which also are referred to as Interim Life Safety Measures, are important to implement for any deficiency, but they come under extra scrutiny when they are being evaluated by an authority having jurisdiction for a waiver application. When facilities managers implement ALSMs, they should document everything. That way, if issues arise, they can show that they did their part to make sure patients were not adversely affected.

Leah Hummel, AIA, CHFM, CHC, CHOP, SASHE, is senior associate director, ASHE Regulatory Affairs, at the American Society for Health Care Engineering. She can be reached at lhummel@aha.org.