The facilities manager and health care finance

Facilities and finance professionals need to create a level playing field where they can understand each other and communicate in a respectful and open way.

Image by Getty Images

Health care facilities managers must ensure that their facility functions to meet the ever-changing needs of patients and their health care providers, as well as the needs of all staff and visitors. Without facilities managers and their teams, patients can’t access the services they need to maintain their health and treat their health care conditions.

That’s why facilities managers need a better understanding of where they fit into their organization’s financial picture. By learning the language of finances, understanding who the various executives and managers with financial oversight are (and their roles) and educating themselves on how the hospital is structured financially, facilities managers will be further empowered.

When facilities managers prioritize frequent, respectful and open communication with their colleagues in the finance department, they’ll gain an understanding of how the overall budget process operates, where their department fits in and how they can work together to create the best possible outcomes.

To help, the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) recently published Optimizing Health Care Finance: The Facilities Manager’s Handbook, from which this article is excerpted and edited. The full 156-page book can be purchased by visiting the Health Care Facilities Management Essentials Series webpage.

The finance function

A health care organization’s finance department oversees the accounting and financial management activities of the organization’s facilities. These activities include establishing financial policies, ensuring the production of accurate and timely financial statements, budgeting and forecasting, capital planning and return on investment, labor management reporting, margin management, asset and resources decision-making, accounts receivable, payroll and accounts payable. They also can include overseeing patient records and clinical documentation.

Essentially, the finance department supervises the intake of revenue from insurance companies, government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid and self-pay patients, and oversees the outflow of revenue within the health care facility to support patient care activities.

Operating expenses are the day-to-day costs that come from running the health care facility, while capital expenses are larger purchases with a useful life beyond one year. To accomplish these activities, the finance department is managed by specific individuals, which include the chief financial officer (CFO), directors, managers and supervisors.

The department is broken down into subdepartments, which carry out the more specific financial functions. The size and job functions of the organization’s finance department will be dependent upon a variety of variables, including the size of the hospital or health care organization. The makeup of the finance subdepartments also depends on the size of the organization. However, most health care organizations have finance subdepartments that include accounting (accounts payable, payroll and financial statements), decision support (budgeting, forecasting, capital planning, labor standards and revenue integrity), patient financial services (registration and accounts receivable) and patient records (medical documentation, coding and patient charts).

The CFO works very closely with the organization’s chief executive officer (CEO), chief operating officer and other members of the executive leadership team to make decisions. The members of the executive leadership team report to the CEO, who then reports to the organization’s board of directors.

The board of directors is responsible for overseeing the overall operations of the health care organization. They delegate the actual operation to the CEO, who hires the rest of the executive leadership team. Those executives then hire directors to carry out the various functions of their departments. Those directors hire managers, who, in turn, hire supervisors and personnel to staff their departments.

Learning the language

When facilities managers use the language of finance with their CFO, they create space for a good working relationship and understanding, regardless of how operating and capital budgets shake out in any particular year.

It makes sense to play the long game because, over time, they’ll forge better relationships, increase their understanding of the trade-offs involved in budgets and help their colleagues in finance understand the importance of maintaining and improving the facility.

Taking the time to add this new vocabulary to their skill set will help facilities managers make cost-effective decisions within the budgets and capital improvement requests they compile and submit. They’ll also be able to present their budgets and capital improvement requests using sound financial principles.

There are several important financial terms facilities managers must understand. Some of these include:

- Assets. These are tangible or intangible items owned by the health system that provide current and future benefit. They include cash, real estate, equipment, accounts receivable, patents or trademarks. Assets are usually divided into current assets, which can be converted into cash within a year, and fixed assets, which have a longer life.

- Balance sheet. This is a financial document that communicates the worth of a health system by listing the assets and liabilities. It is one of the three major financial statements utilized by CFOs and other executives, along with the income statement and statement of cash flows.

- Capital budget. This reflects the items with a cost and life expectancy that fit the health system’s definition of capital. Health care facilities managers use the capital budget to purchase tools and equipment and undertake upgrades to reduce operating costs. Managers should create a five-year plan for major systems and list the following for each utility/system to begin creating a capital budget plan: age; condition; expected remaining life; predicted life-cycle cost from now until the end of expected life; expected replacement cost; cost; and expected replacement date.

- Cash flow. This tells how many dollars are coming in and going out at any given time. Cash flow is a critical metric for CFOs, because if more money is going out than coming in, the organization will need to borrow money to cover the temporary shortfall.

- Deferred maintenance. The definition of deferred maintenance is “maintenance and repairs that were not performed when they should have been or were scheduled to be and which are put off or delayed for a future period,” according to the Department of Energy. Health system revenue shortfalls lead to the need to defer some maintenance tasks and repairs. To determine which maintenance repairs are necessary, facilities managers can consider whether the specific repair is required from a compliance or internal policy standpoint.

- Depreciation. This is a financial mechanism to spread the cost of a capital asset over its useful life. Health care systems depreciate assets for both tax and accounting purposes. There are different methods used for depreciation of assets in different situations.

- Expense. This is a cost incurred to generate revenue or the reduction of the value in an asset as it is employed to generate revenue.

- For-profit entity. This is an entity that operates with the goal of making money by selling goods or services to the public.

- Full-time equivalent (FTE). The Bureau of Economic Analysis defines FTEs as the number of employees on full-time schedules plus the number of part-time employees converted to a FTE number. One FTE is equal to 2,080 paid hours per year, in which the 52 weeks of the year are multiplied by five working days a week and eight hours a day of work.

- Income statement. This summarizes the income and expenses in a health care system or a subsidiary over a period of time, usually quarterly and annually. Income statements, which also are known as profit and loss statements, include the cumulative impact of revenue, gains, expenses and losses. It is one of the three major financial statements utilized by CFOs and other executives, along with the balance sheet and statement of cash flows.

- Interest rate. This is the rate paid to borrow money, which is generally expressed as a percentage. Interest rates are typically stated on an annual basis.

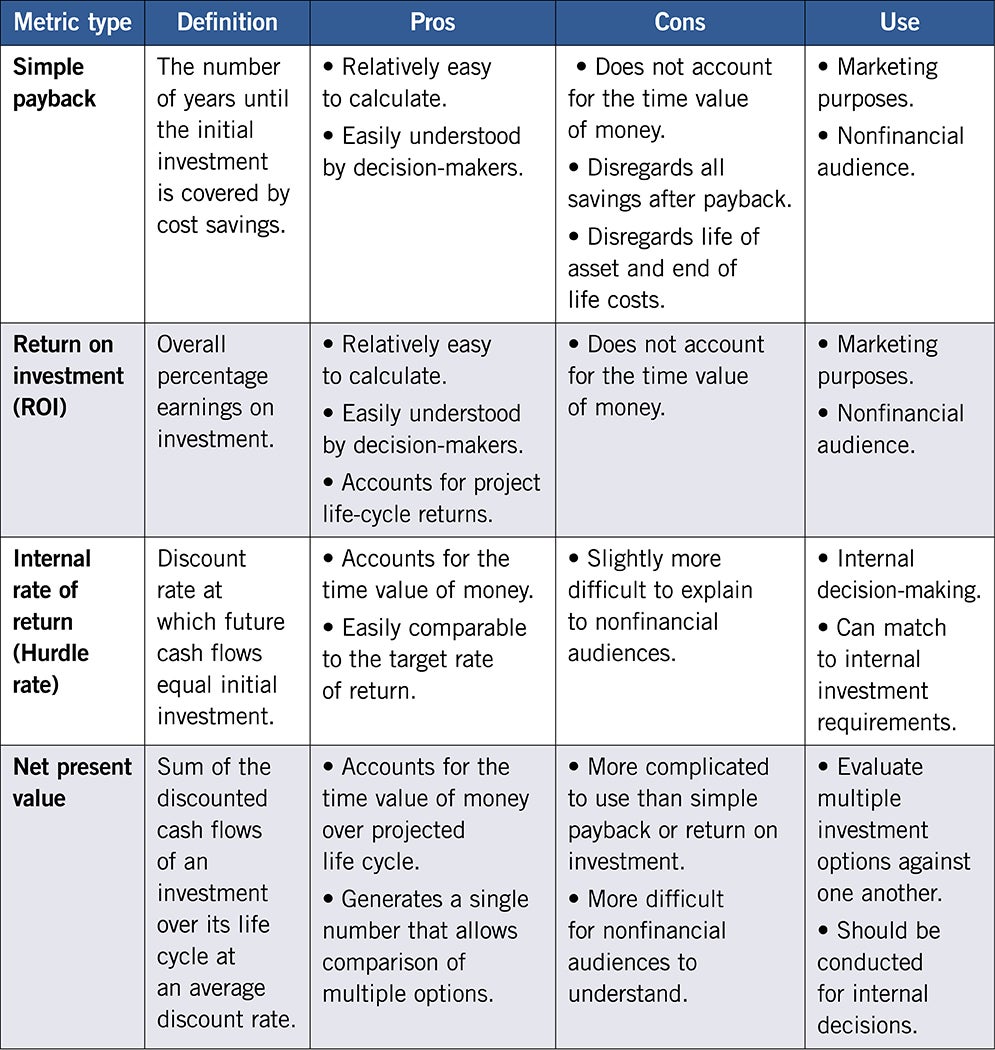

- Internal rate of return. This is the rate that will be realized when the cost of the investment equals the net present value of the savings over a set period.

- Life-cycle cost. This estimates the total capital, operating and maintenance cost of an asset during its operational life. Facilities managers employ life-cycle cost to justify the purchase of replacement equipment.

- Net present value of a capital item. This is the value of a capital project in today’s dollars over a defined period, related to time value of money. It takes savings, cost, revenue, salvage value and the period over which things occur into account.

- Nonprofit entity. This is an organization designed to further a social cause and provide a public benefit that qualifies for tax-exempt status from the federal Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Nonprofit organizations, which include hospitals, universities, foundations, charities and more, are required to disclose their financial and operating information to the public. To qualify for tax-exempt status, nonprofits must be certified by the IRS as 501(c)(3) organizations, which means they are exempt from federal taxes on revenue, as well as state sales, property and income taxes. However, nonprofits must pay the employer’s portion of their paid employees’ Social Security, Medicare and unemployment taxes.

- Operating budget. This reflects the day-to-day cost of running the health system. These budgets should be based on factors such as history of costs, going back at least five years; projected cost increases; and changes to the facility.

- Productivity. For facilities management departments, productivity is measured by the finance department by dividing the FTEs by the square feet involved. This doesn’t necessarily work well in practice, as not all departments are the same and it’s hard to be sure exactly what is included in the square foot number — parking lots, grounds, roof and so on. In addition, it is not uncommon for health care organizations to use an external benchmarking firm to determine productivity standards for various departments, including facilities. They typically use a benchmarking database they have developed.

- Return on investment (ROI). This is calculated by dividing a capital project’s net profit by its cost. Facilities managers can then use the resulting percentage to compare the ROI on a variety of projects, which will help the facilities manager and the CFO understand the efficiency behind different capital improvement projects.

- Reorder quantity. To track when they need to order supplies and how many supplies to order, facilities managers use a formula that multiplies the average daily usage by the lead time in days plus the safety stock. For example, if a facility consumes eight light bulbs a day on average and it takes a week to get the order delivered, the manager should multiply those eight bulbs by seven days to get the total they need to order, which would be 56 bulbs. A safety stock of 16 bulbs, which is a two-day supply, would tide the facility over if the order was delayed for some reason. It’s important not to over-order because parts and supplies tie up a health care facility’s capital. Also, storing supplies takes up valuable space, and supplies can be lost, damaged or become obsolete.

- Revenue. This is the total amount of money brought in by an organization’s operations measured over a specific period. Revenue is calculated before expenses are subtracted.

- Simple payback period. This refers to the amount of time involved in recovering the cost of a capital improvement. Facilities managers also can think of it as the break-even point. To calculate a simple payback period, they should divide the amount of the investment in the capital improvement by the annual cash flow.

- Statement of cash flows. This records how cash flows in and out of a health system during a specific reporting period. It is one of the three major financial statements utilized by CFOs and other executives, along with the balance sheet and income statement.

- Sunk cost. This is the amount of money already spent on repairs for specific pieces of equipment. When evaluating whether to repair or replace equipment, the only factors facilities managers should consider are cost of needed repair (some of the expense will not be considered sunk if they extend the life of the equipment); cost of future maintenance; and predicted lifespan of the equipment after repairs.

- Time value of money. Money is worth more today than it will be in the future. Why? Because the value of money is constantly eroded by inflation. Organizations also could invest money today, increasing its present value. Finally, money that facilities managers possess now is a certainty, whereas money they will receive in the future is subject to uncertainty. Facilities managers need to understand time value of money because this is how CFOs evaluate the financial impact of capital improvement projects. The concept allows them to compare the cost of a project against the potential future cash flows that will be generated by a project.

Financial best practices

When facilities managers decide to embrace the financial side of their job, that investment will pay off in their increased ability to advocate for their department’s priorities and decreased levels of frustration around the budgeting and capital improvement processes. For example, when they understand how their FTE staffing standard relates to the operational cost per square footage of their facilities, they realize how important an accurate square footage count will be.

If managers analyze their health system’s budget, they’ll notice that, typically, approximately 55% of all expenses are labor-related and 20% are supply-related. Taking that down a level to their budget, managers can see that it’s worthwhile to spend time understanding how the budget is allocated so that they can better decide how to expend their time and energy.

Facilities managers may encounter a financial staff member who assumes, for example, that facilities should be able to do monthly maintenance for a certain amount of dollars. But that may be based on a once-a-month schedule, whereas facilities need to do it three times a month to stay in compliance with manufacturers’ standards for use. If managers can speak to that and tie their reasoning to staying in compliance, that can make a difference in budget negotiations.

Inpatient and outpatient volumes are a place where health systems’ budgets live and die. However, volume has a different impact on facilities staffing than it does on patient care labor, as Jonathan Flannery, MHSA, CHFM, FASHE, FACHE, senior associate director of regulatory affairs at ASHE, explains. “When the patient census is down, more maintenance can be performed in a shorter period of time, which provides for more productivity and less cost than when the census is high. That means that facility operating costs could actually go up when the census is down,” he says.

In general, revenue drives the ability to have capital investment and, obviously, cover facilities department expenses, including staff.

Bridging the communication gap

When facilities managers can communicate the financial and patient care implications of a facility’s assets to the finance team, they are more likely to understand what is needed and why and help fit it into the list of overall organizational capital priorities.

Facilities managers should strive to set up their capital and operating budget requests through the following framework of questions:

- What problem are we solving?

- Why are we solving this problem?

- What is the benefit?

As these discussions occur, facilities managers may not understand everything that their colleagues from the finance department are saying, but they shouldn’t be afraid to ask questions. Most financial team members are happy to explain.

About ASHE’s finance handbook

The accompanying main article is excerpted and edited from the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s (ASHE’s) Optimizing Health Care Finance: The Facilities Manager’s Handbook, which provides the financial insights, skills and tools health care facilities managers need to secure vital resources for their department. The article is primarily excerpted from the chapter titled “Part 1: Finance and the Facilities Manager’s Role,” but other chapters cover health care finance basics; evaluating bids for equipment and services; contract negotiation; contract management; understanding payback potential, return on investment and related financial methods; operating budgets; capital planning and budgeting; and managing building, property and equipment leases.

ASHE extends its sincere gratitude to the individuals who offered their time, knowledge and effort to the creation of this book.

- Lead author: Tim Panks, MBA, is a seasoned financial health care executive and CEO of the Panks Consulting Group LLC.

- Contributors: Nick Chaput, MHA; Cindy de Moya, CPA; Jonathan Flannery, MHSA, CHFM, FASHE, FACHE; Renée Robison Jacobs, CHFM, CHC, FASHE; Kenneth Knight, BSME, MSIE, MBA, CHFM, FASHE; Edmund Lydon, MS, CHFM, CHEP, FASHE; Shadie (Shay) Rankhorn Jr., CHFM, CHC, FASHE; and Walt Vernon, MBA, PE, FASHE.

- Editors: Chris Dimick and Corrie Fisher, MEd.

ASHE also would like to thank Amy Buttell for her writing collaboration and editorial assistance on the publication, as well as its partners at Jenkins Group Inc. ASHE also thanks the Healthcare Financial Management Association for its assistance with the publication.

To learn more or to purchase a copy, visit the Health Care Facilities Manager Essentials Series webpage.

This article was excerpted and edited by Health Facilities Management staff from the 156-page Optimizing Health Care Finance: The Facilities Manager’s Handbook.