Effective administration for facilities managers

Once a person moves into the administrative arm of facilities management work, they need to hone their ability to forge connections with people.

Image by Getty Images

Health care facilities administration is more high stakes than in other fields because the work is happening in active settings with the most vulnerable people. The risks are greater, the rules more complex and the systems more essential. To be a health care facilities manager means to take on the role of managing those administrative tasks that ensure a well-run, safe facility.

Before a facilities manager can do their job, they must create a structure, a process and performance expectations to empower every member of the team to effectively support patient care. To accomplish this task, they must have a skill set that includes a working knowledge of the administrative elements of management, including:

- Planning — Setting goals and outcomes.

- Organizing — Providing structure to support the team to execute the work.

- Leading — Establishing direction for the tasks and teams.

- Controlling — Defining expectations and parameters for the work.

The American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) recently published the handbook, Effective Health Care Administration for Facilities Managers, part of the Health Care Facilities Management Essentials Series. Its purpose is to help facilities managers and leaders in other parts of the organization understand the general and field-specific management requirements of this position.

This article was excerpted and edited from that handbook.

Managing the space and its function

The first section of the handbook discusses administrative tools and common concerns, safety and security issues, and partnerships over the following four parts:

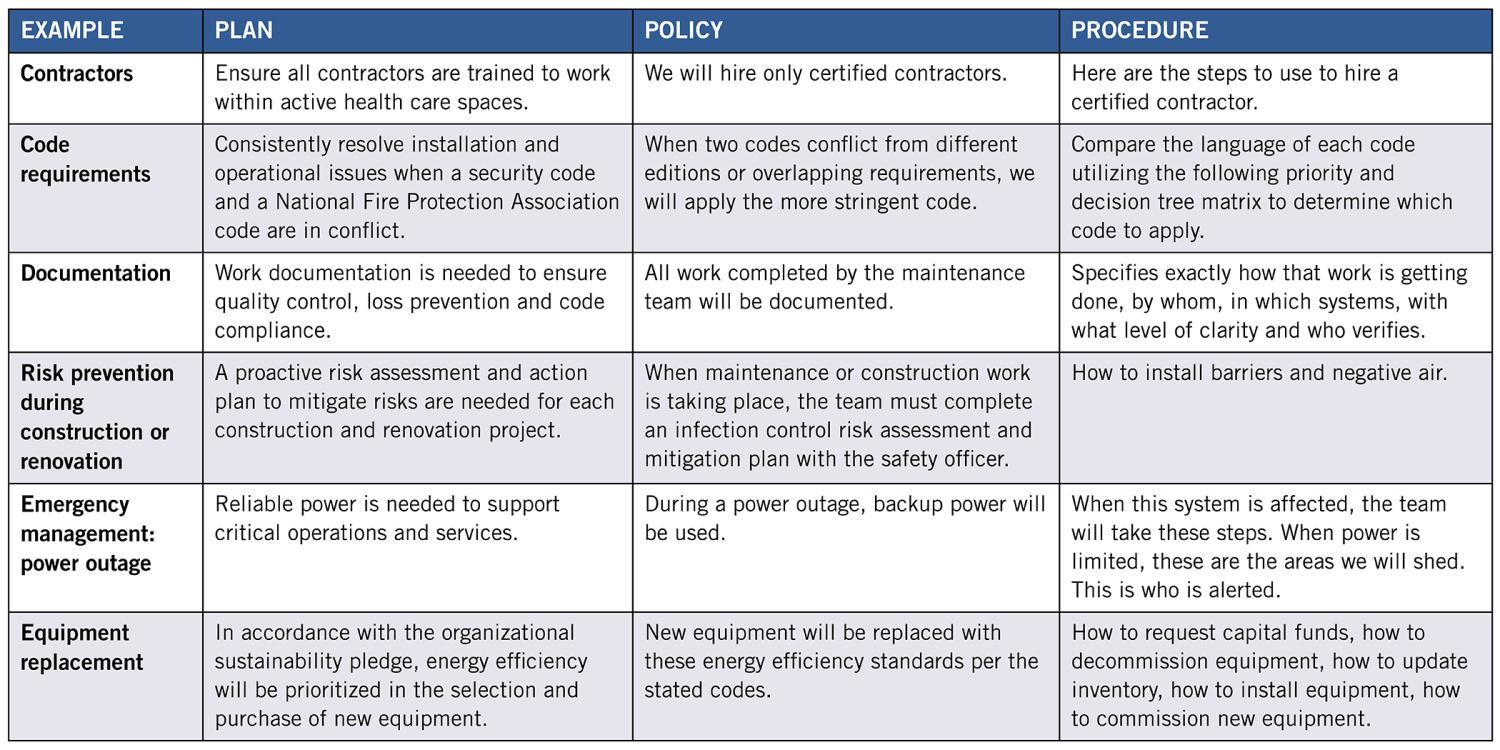

Plans, policies and procedures. Consider the confluence of systems, requirements, risks, redundancies, subunits and employees all operating within the same space in a health care facility. To assert some control over the chaos, a facilities manager needs to engage order, constraints and practices to manage that complexity. This is accomplished through plans, policies and procedures, all of which exist under the area of a facilities manager’s administrative responsibilities. These are critical activities for serving the organization’s mission and providing optimal outcomes for patients. Appropriate plans, policies and procedures also offer continuity of operations during staff turnover or in a management change.

Facilities managers will find that having a good grasp of their organization’s plans, policies and procedures will help them assert control, set goals, define outcomes, provide consistency, set expectations and reduce ambiguity. By understanding the definition and composition of a plan versus a policy versus a procedure, facilities managers can wield these tools effectively (see chart below).

Manage and oversee operations. The work that goes into the creation of plans, policies and procedures is only useful if a manager and their team implement those plans, policies and procedures. The facilities manager’s job may not be to turn the wrenches but to have a sound grasp of how the facility functions and make sure that all the components are working together to keep it running smoothly.

It’s easy for members of the facilities team to get tunnel vision. They know their jobs and do them well, meaning individual equipment or systems are in great shape. However, they may not have the scope of vision to see when the overall system is in trouble. The facilities manager keeps an eye on that bigger picture by assessing performance according to reliability, resiliency and efficiency.

To monitor these factors and make decisions, the facilities manager needs a consistent flow of accurate data and information as well as good communication flowing in and out of the department.

Safety and security management. While health care campuses are dedicated to restoring and protecting human health, that job carries inherent risk. Many people come into health care buildings carrying pathogens, others become more vulnerable to infection while under the organization’s care, and still others present a danger to themselves or others. Environmental threats like fire or flood emerge without warning, threatening people with limited or no mobility. Additionally, many of the tools used in health care facilities are themselves dangerous without proper handling.

Thus, much of the compliance landscape concerns itself with mitigating risks to safety and security, and the task demands the constant attention of facilities managers. The primary job of the facilities manager is to see that an organization’s buildings and systems function reliably. A campus cannot have reliable operations if it does not have a safe and secure environment for the people occupying it. Perhaps the single most important question facilities managers must ask themselves is, “How do we maintain a safe, secure environment every single day?”

(While the handbook discussed in this article is concerned with the administrative aspects of safety and security, the compliance and risk aspects are addressed in depth in the compliance and managing risk installments of ASHE’s handbook series.)

Developing and maintaining important relationships. Once a person moves into the administrative arm of facilities management work, they need to hone their ability to forge connections with people.

This begins with the facilities manager’s own team but doesn’t stop there. While a facilities manager is probably already fluent in “technical speak,” they also need to speak the language of CEOs and CFOs, service-line managers, nurses, physicians and every other professional in the building. Additionally, they will be required to communicate with stakeholders outside their organization, such as surveyors, municipal officials, utilities providers and first responders.

Developing and nurturing professional relationships is critical for facilities managers. It starts by identifying the professionals requiring a relationship with facilities management and determining what the facilities team needs from them and what they need from the facilities team. Relationship development is key to performing the administrative aspects of a facilities manager’s job while also enhancing the facilities manager’s potential for upward mobility.

Trust is the coin of the realm in health care organizations. Leaders throughout the organization quickly identify who they can trust and who they can’t. Facilities managers must learn to consistently display personal and professional credibility that will encourage others to trust them and serve as the foundation of a positive relationship.

Managing the team

The second section of the handbook discusses skills needed to build an effective facilities team, the logistics of distributing these resources and required training over the following three parts:

Staff management. A strong partnership between managers and front-line workers is essential for any organization to achieve its mission, and these relationships depend on communication, collaboration and trust. To create this foundation, a manager often must develop new skills and competencies beyond the technical skills that likely got them through the first stages of their career. Often called “soft skills,” these are grounded in human interaction, which determines how relationships are formed and grow.

There are practical skills that work in tandem with soft skills and center on hiring the right people, preparing employees for their jobs and making sure the organization takes care of its facilities employees.

Labor distribution. Every health care organization has its own requirements, which means the facilities department must tailor itself and its labor distribution to the needs of each facility. Factors that influence organization and staffing decisions include where the facility is located, what service lines and specialties it provides and the physical layout of the campus. These variables are why there is no one-size-fits-all facilities management staffing plan. However, there are common practices that are useful to the health care facilities manager when evaluating and improving their staffing plan.

Staff training. Training literally can be the difference between life and death. For example, zone valves are critical to stop the flow of oxygen during a fire, but accessing an incorrect valve could be fatal to patients on respirators.

Thorough staff training matters not only to patients but also to anyone who enters the health care campus. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has developed a tool to aid in staff training within the health care environment. Even basic facilities jobs require training to handle the complexities of the environment.

Managing resources

The third section of the handbook discusses administering materials and equipment, capital planning, advocating within the organization and articulating the value proposition when requesting resources over the following four parts:

Inventory and supplies management. One of the most important lessons of events like the COVID-19 pandemic is to not take the supply chain for granted. At times, the ability to provide care was disrupted by inventory deficits for critical items such as personal protective equipment.

When a repair or delayed maintenance takes equipment offline, the repercussions can be serious. At minimum, it frustrates team members who must wait for parts or supplies; at worst, it can disrupt patient care.

Ensuring that parts and materials are readily available is an important administrative responsibility of the facilities manager and should never be left to chance. Effective inventory and supplies management are about keeping the department well supplied without making excessive demands on budget or storage space.

Capital planning administration. Consistent access to capital is essential to ensure reliable operation of existing systems, meet the growing needs of new clinical service lines and integrate new technologies. Thus, facilities department leaders need a thorough understanding of the capital planning process, including the factors that executive leadership uses to evaluate capital budget requests.

Most organizations have a finite amount of funds available for capital budget requests and must consider a complicated mix of factors, including operating margins, depreciation, charitable donations and additional debt. Consequently, competition for funding can be fierce, and even projects with excellent financial returns may not be approved.

Typically, organizations establish capital budgets on an annual basis using an existing schedule, which establishes deadlines for submitting requests, evaluating requests and creating the final capital budget. The capital budget request process is usually managed by a committee, which evaluates capital requests, ranks them in order of importance based upon their justifications and provides approval/denial recommendations to executive leadership.

Organizations often create specific forms for capital budget requests, asking that the requesting department offer a complete project description, estimated cost and justification. Common justifications for capital budget requests include expanded or additional services that increase operating margins, regulatory compliance, improved life safety, improved infection control, energy cost reduction, staffing cost reduction, enhanced physician relations and deferred maintenance.

Demonstrating departmental value. Health care facilities departments are essential but typically unnoticed unless something goes wrong. That invisibility can be a serious issue because if the facilities department has not proven its value to health care executives or other stakeholders, getting necessary funding and other support can be a struggle.

If executives do not see the value of the facilities department or trust that the facilities team will achieve the objectives detailed in a funding request, the chances of getting approval for funding are slim. It isn’t enough to deliver on daily commitments because reliable, efficient operations and on-time/on-budget project delivery are baseline expectations.

Thus, advocating for the facilities department’s needs begins long before any funding request is made. If the facilities department is seen as an essential, well-run part of the organization, resources may flow more smoothly.

Once a facilities manager has proven that they can consistently deliver on their commitments, they need to communicate the department’s successes in ways that clearly illustrate the value that facilities generate for the overall organization.

Advocating for resources. Health care facilities managers are leaders in reducing organizational costs through energy savings and implementing operational efficiencies. Yet while their instinct is for efficiency, this cannot come at the cost of reliability and resiliency.

Technical and administrative priorities may sometimes seem at odds — one instinct says, “we can fix this and get another year’s use out of it,” while the other knows that no equipment lasts forever, and the worst time for it to fail would be during an emergency. A facilities manager must find the balance between these two instincts, as no one can effectively advocate for resources when paralyzed by internal conflict.

Executive leadership depends on facilities managers to know the facility’s needs and to speak up so those needs can be addressed. Facilities managers should be confident that they are speaking for the facility when they are advocating for resources.

Detailed financial guidance is provided in another installment of ASHE’s handbook series, Optimizing Health Care Finance: The Facilities Manager’s Handbook.

Improving every day

The Effective Health Care Administration for Facilities Managers handbook will assist facilities professionals in their journeys to become fully competent and confident health care facilities managers.

Executive leadership entrusts facilities managers with the largest single asset of the organization. With that trust comes a solemn responsibility to ensure that the facilities team and the facility they operate are at their best every day.

Reliable delivery of services is not the goal but an expectation that does not waiver under the harshest environmental conditions or intense patient surge. This requires thoughtful planning, clear and persuasive communication, negotiation, early detection and quick resolution of problems, and a burning desire to improve every day.

About the handbook authors

The American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) extends its gratitude to the individuals who offered their time, knowledge and effort to the creation of the handbook discussed in the accompanying article.

- Dale Woodin, CHFM, FASHE, has 40 years of experience in the health care facilities management and health care administration fields.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Illinois, Woodin established the biomedical engineering shop at Northwest Community Hospital in Arlington Heights, Ill. In the 1990s, he served as director of plant operations and later took on the additional responsibilities of safety officer and member of the hospital CEO’s performance improvement council.

In the 2000s, Woodin joined the ASHE team as director of advocacy. In the 2010s, his role expanded to the American Hospital Association’s senior executive director of infrastructure services and then to vice president of professional membership groups. He retired in 2021.

Contributors

- Chad E. Beebe, AIA, CHFM, CFPS, CBO, FASHE

- Krista McDonald Biason, PE, SASHE

- Robert Blakey, MRICS, CHFM

- Danielle Gathje, MBA, CHFM, SASHE

- Russell Harbaugh, CHFM, CHEP

- Gordon Howie, MS, CHFM, CHC, SASHE

- Shadie (Shay) Rankhorn Jr., CHFM, CHC, CxA, FASHE

- Jordan Northcutt Plyler, SASHE

- Bradley S. Pollitt, AIA

- Mike Schiller, FAHRMM, CMRP

- Jason Tate, CHFM, CEM

- Taylor Vaughn, MBA, CHFM, CHC, SASHE

ASHE also would like to thank Carolyn Roark for her writing collaboration and editorial assistance, as well as its partners at Jenkins Group Inc.

This article was excerpted and edited by Health Facilities Management staff from the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s Effective Health Care Administration for Facilities Managers handbook.