Going downtown

About this articleThis feature is one of a series of quarterly articles published by Health Facilities Management magazine in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects. |

Many medical centers consist of an incoherent assemblage of incongruent "thick" buildings, additions and mazelike corridors in which one easily gets lost, surrounded by vast, treeless parking areas. They often comprise a series of opportunistic building projects conceived to meet immediate needs, rather than being able to accommodate change and growth over time.

In fact, the lifespan of a typical master plan is rarely longer than the next major project or architect. At worst, the least efficient and oldest structures on campus become encapsulated by surrounding additions and newer construction, making their demolition and replacement ever more difficult and expensive.

But the physical environment of the medical center campus should be an ongoing reflection of the mission of any health care organization — to maintain and improve health at the level of the individual, the community and globally through environmentally responsive design. It also should accommodate change gracefully and efficiently over time.

Healthy, flexible and sustainable master planning can be achieved over the life of the campus only if it is implemented, organized and maintained through sound urban design strategies.

Health care drivers

Campus master planning must respond to a range of health care drivers such as efficiency, health and safety. Campuses should promote patient, family and staff satisfaction and help to attract and retain productive staff. They must support positive health care experiences for a wide range of people over time. Some key drivers that inform campus planning include:

Operational efficiency and effectiveness. Optimizing efficiency and effectiveness, particularly through Lean processes, is critical for health care organizations. Yet, little effort has been focused on the impact of the campus layout and configuration on organizational operations. It stands to reason that a campus with a convoluted mazelike configuration based on the optimization of its parts rather than the whole is inherently less efficient to operate than one organized for flexible uses, growth over time and the efficient movement of people, materials and services.

Health and safety. An ever-growing body of research establishes fundamental relationships between the built environment and measures of patient health status and outcomes as well as safety. However, most research has been focused on specific care settings, not the campus. Sustainable design also is inherently a health issue. It is clearly relevant to master planning given that many Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) credits are impacted at the level of the campus master plan. Healthy community planning and design also are recognized as having an impact on health. A medical center campus is a community in scale and function. Healthy hospital and healthy community planning and design are now being considered in health care projects like the HDR Inc.-designed Focal Point Community Campus, planned for the southwest side of Chicago.

A complete experience. Significant emphasis has been placed on creating patient and family-centered health care environments in the past two decades. However, more attention has been placed on the interior than the exterior environment. Yet, arriving on campus, finding where they need to go, parking and then navigating the overall building complex is the first impression many people have of their medical experience and it is rarely a positive one. The campus also provides the localized landscapes that people move through and view from patient rooms as well as from lobbies, atria or waiting rooms.

Accommodating change. Of course, the bottom line for each of these drivers is doing more, better and with fewer resources at lower costs — now. The less-considered part of the economic picture is the relationship between initial capital costs and operational costs over the life of a building or campus; nor is the cost of accommodating change considered. The emphasis of many health care organizations on master planning and building projects typically has been on first costs and short planning horizons. However, the lifespan of a health care facility can be 50 years and that of a campus much longer.

Many health campuses have grown and evolved into inefficient and incoherent places because they were not able to accommodate the ever-increasing rate and magnitude of changes in health care. The only constant in health care is change: in treatment and technology, in disease and patient demographics, and in reimbursement and regulation. Therefore, master planning must accommodate what and how health care is provided today and changes that can't be imagined over the lifespan of the campus.

Urban design problem

Parallels between hospitals and cities have been established elsewhere. Most medical center campuses operate at the scale of a small city or district. They frequently are the major employers in their communities, touch the lives of more people and often have great impact on both community infrastructure and overall carbon footprint. As an urban design problem, campus master planning should address the following principles:

Provide an open, yet stable, urban grid. The fabric of streets and alleys creates a permanent armature for movement and services in a city. While city streets are stable, the city block is in a constant state of flux. Buildings are constructed, retrofitted and demolished; uses change and tenants come and go. Stable right of ways guarantee access to the blocks for people and services as they change over time.

A hospital campus likewise needs to be formed and maintained around a grid of stable pathways, stable public spaces and flexible blocks for building footprints and functional space. The urban grid does not need to be rigid or strictly orthogonal. In fact, some irregularities in the layout of paths and blocks can help with orientation and provide a spatial hierarchy to aid in wayfinding.

Like cities, a health campus needs a hierarchy of pathways including major boulevards, neighborhood shopping streets, secondary streets within neighborhoods, side streets as either interior or exterior pedestrian pathways, and alleys for back-of-the-house movement and distribution of services. A legible and stable network of pathways along with nodes and landmarks is essential for maintaining clear wayfinding as the campus evolves over time. Major pathways should be open and extendable to accommodate growth within and beyond the original campus.

NBBJ's Banner Estrella Medical Center in Phoenix represents a building and campus master plan with an urbanlike fabric organized for growth and change. The campus is organized along a primary spine that provides public circulation at and above grade, with materials and services below ground. This is anchored by the physical plant, central services and receiving at one end of the site and medical office functions at the other end. The entry is signified by a landmark element or space. Flexible and expandable zones for diagnostic and treatment functions are organized on one side of the spine with multiple inpatient pavilions on the other. Secondary pathways at the front and back of the house link inpatient and diagnostic and treatment areas to the spine and to each other.

The first challenge in master planning is to establish a flexible fabric of streets and functional blocks that can accommodate changing needs over time and anticipate needs that cannot be foreseen when the plan is established. As in a game of chess, it is important to visualize and plan for multiple potential scenarios or moves many steps ahead. Also, as in chess, each piece has limitations on how and where it can move and the constraints are always changing. The arrangement of city blocks becomes the chessboard and forms additional constraints for movement. Their location, size and configuration determine what moves are possible.

U.S. hospitals typically have thick building blocks devoid of daylight, especially in diagnostic-treatment and clinical areas. Yet, efficient and flexible diagnostic and treatment areas can be accommodated in zones of space approximately 100 to 120 feet wide with adjoining support and circulation zones as designed at Palomar Health's Pomerado Hospital near San Diego. While an overall building block may be thick, perforations can be inserted for daylight and courtyards in circulation and support zones.

Create a campus without walls. Health care campuses often are isolated from their communities outside of town and surrounded by acres of paved, minimally landscaped parking; or they are institutional districts within cities with internally focused fortresslike buildings that can intimidate surrounding residential neighborhoods. In either case, they usually become go-to places rather than pass-through places that are accessible, inviting and desirable as a part of everyday life.

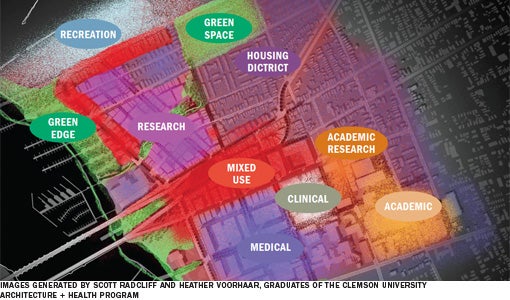

Clinical and nonclinical uses should be combined seamlessly to create a campus that supports and promotes health, encourages community engagement and becomes a livable, mixed-use environment. The campus should add life and value to the larger community. Ground floors and public spaces in institutional buildings should include community and commercial uses and be functionally and literally transparent, open to the street and public spaces outdoors at grade. Functional zones for inpatient care, ambulatory patients, research and teaching should be defined by their centers with blurred boundaries and mixed complementary uses at their peripheries. A campus should include soft permeable boundaries and buffering when necessary to temper the impact of activities from surrounding neighborhoods. The fabric of campus streets and pathways should be an extension of the network of streets in the surrounding community.

Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago represents a campus that is seamlessly woven into its dense surrounding neighborhood. It exists within the grid of city streets with connections between buildings maintained through a series of pedestrian bridges and underground services. Its buildings are significant in scale and bulk. However, they open to the street at multiple places on lower levels and street trees mask the scale of the buildings to pedestrians. People in the surrounding community enter, pass through and use the commercial services located on lower levels.

Lobbies and atria serve as extensions of the public realm in the community. The medical center contributes to the vibrant mixed-use nature of its neighborhood, rather than acting as an institutional, inwardly focused fortress.

Provide a variety of therapeutic green spaces. A substantial body of research indicates that views and access to nature can have healing and stress-reducing benefits. Therefore, a variety of permanent green and civic spaces should be designed on a campus as both active and passive public amenities that are open, attractive and usable to the community at large. They can include urban parks, pocket parks, courtyards, roof gardens, tree-covered parking lots, networks of green streets and entry plazas that also act as civic gathering places, such as proposed by HDR for Focal Point.

Green spaces provide buffers and blurred boundaries between clinical and nonclinical areas, views to nature from within clinical settings, therapeutic spaces to pass through and important places to seek connections with nature. They can be activated by providing outdoor cafes, seating areas, water features, views and connections to major pathways on the campus. When located along major campus entry paths, they can help to provide wayfinding cues that are welcoming and calming.

The Universitatsspital Basel hospital in Switzerland provides an urban oasis in the middle of the city. A large green space is located at the center of the campus and functions as a city park used by the public, staff, patients and visitors. It buffers clinical areas from the public eye, but allows views to nature and city life from surrounding clinical buildings.

Provide low-impact parking. A significant challenge to any hospital campus is providing adequate and accessible parking. Most campuses are dominated by surface parking lots or challenged with finding adequate parking in an urban context. Conventional surface parking lots have a significant environmental impact in terms of creating heat islands, producing storm water runoff and generating light pollution. The classic master plan locates the building complex at the center of the campus surrounded by a sea of parking that prevents it from integrating with the surrounding community in a healthy and walkable way. These harsh landscapes are not welcoming or safe environments to traverse, especially during hot, rainy or wintery days.

There is no single parking solution. Rather, multiple strategies must be employed to collectively accommodate healthy and environmentally responsive parking needs. Larger parking areas should be minimized and located so they are dispersed checkerboard fashion in dedicated zones. Distributed on-street parking within and around the campus should be employed whenever possible to satisfy some short-term parking requirements. On-street parking can act as a traffic-calming strategy and make sidewalks safer for pedestrians. Restricted small parking lots nestled between and around buildings can be employed for handicapped access and personnel who must migrate on and off campus during the day. Structured parking should be employed whenever possible under plazas and green spaces, or located midblock between buildings. They should be designed with access to daylight at stairways and elevators as a wayfinding cue.

When large surface parking lots are necessary, they should be planted with trees adequately spaced, selected and sized to provide shade during the summer. This forms a therapeutic landscape through which to move and view from buildings.

Healthier and sustainable

Collectively, these practices can help to create a campus master plan that is healthier and more sustainable over time.

For existing medical centers, these principles will need to be applied to conditions of campus repair, restoration and reconstruction. Change will occur incrementally and piecemeal over time.

Some of these strategies cannot be implemented unilaterally and likely will require community engagement. For instance, public spaces and street improvements will require addressing mutually shared goals. It may be appropriate to cede land or provide easements to the city.

The development of public space on the campus also may require a creative mix of funding given the constraints on both health care capital and public funding today.

David Allison, FAIA, FACHA, is an alumni distinguished professor and director of Clemson University's graduate program in architecture and health. He can be contacted at ADAVID@clemson.edu.

| Sidebar - Campus planning resources |

| There are a number of publications, papers and articles that touch on health facility design as it relates to campus planning. Following are resources the author used in the preparation of this article: • Allison, D. "Designing Hospitals and Medical Centers as Healthy Livable Urban Districts," 49th International Making Cities Livable Conference, Portland, Ore., May 2012. |