Small hospitals, big rewards

Designing and building a hospital using evidence-based best practices is a complex business for anyone, but all the more so in rural environments that often do not have the same resources as larger or academic institutions. But a common sense approach can help rural facilities take advantage of evidence-based design practices and concepts and improve on processes based more on past experiences and instinct.

Designing and building a hospital using evidence-based best practices is a complex business for anyone, but all the more so in rural environments that often do not have the same resources as larger or academic institutions. But a common sense approach can help rural facilities take advantage of evidence-based design practices and concepts and improve on processes based more on past experiences and instinct.

First, a quick look into the issues being addressed by evidence-based design shows that many practices already valued by architects and owners are being validated by objective research. For example, designers and hospitals have long valued design elements such as abundant daylight and views to the outside, as well as access to plants and nature. Evidence-based design supports a correlation between access to natural daylight and better patient outcomes. Patients with views of nature and access to high levels of daylight have lower use of pain medications and improved sleep patterns. Natural daylight can also help reduce patient depression and stress levels. Large windows are easy to include in patient rooms at new rural facilities and represent the kind of simple evidence-based design element that we regularly implement in our projects.

|

| This lobby brings the "outside in" with abundant light, plants and complementary colors and materials. |

Sales point for the community

Evidence-based design offers the opportunity to consider these types of design practices not simply as "nice to have" in a new project, but as a proven and integral part of the patient care environment.

Objective studies allow designers and administrative teams to share information with their communities on the importance of these approaches as a fundamental part of the healing environment perhaps not fully appreciated in past projects. Many rural facilities instinctively understand the value of good design as a part of their projects, and the use of evidence-based design research can help their communities understand the reasons for investing in good design in their local hospital.

Use of color is another approach that is easily implemented in new rural projects. While color remains a contested element of therapeutic design, certain studies suggest that the value of color may be more scientific rather than aesthetic in nature. Studies show that the rods in human eyes respond differently to different wavelengths of light. For example, the wavelength that produces red requires the eye to adjust to catch it. Therefore, in purely physiological terms, red is an agitating color. Blue and green wavelengths are easier for the eye to perceive and, therefore, these colors are physiologically restful. One study on the effects of visual stimulation on patient recuperation found that patients in "vibrant" surroundings recovered three-quarters of a day faster and needed fewer pain killers, than those who did not. Evidence-based design suggests it is better to err on the side of color than the lack of it.

|

| This nurses' station incorporates a carefully selected color palette and is strategically designed to separate noisy staff activity from the public space. |

While science may not yet be able to explain the extent to which specific colors impact individuals, or how specific colors may be used to achieve universal results, many psychiatrists and psychologists studying the subject agree color has the effect of directing an individual's attention outward, providing a diversion that can relieve mental tension.

Other concepts

Other easily incorporated evidence-based concepts relate not so much to the layout and visual appearance of the completed project, but more to the systems and finishes that make it work. Infection control is of vital importance to all hospitals, and EBD provides valuable insight in how new designs can improve outcomes.

Construction practices should take advantage of research into temporary airflow measures to improve infection control such as negative air pressure and air barriers between construction areas and patient care areas. Mechanical systems should support good air quality through proper filtration, effective ventilation, and appropriate pressure relationships. Engineering for water systems should reflect evidence regarding optimal temperature and pressure as well measures to avoid stagnation and backflow. Finishes should be selected to support proper cleaning and disinfection procedures.

Evidence-based design can help identify design issues that are particularly important to address during the development of a new rural facility, rather than attempting to address at some future point.

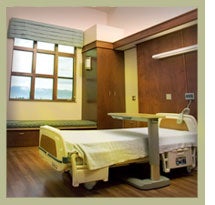

|

| This private room features a day bed to promote family interaction and large window to provide outdoor views. |

For instance, wayfinding is an important component of reducing patient stress in a hospital visit and improving patient satisfaction. Studies show that the most frequent solution, a system of signage overlaid onto an existing building or completed design, is usually ineffective. Research indicates that hospital wayfinding is far more effectively addressed by the overall structure of the design. Providing outside views for visitor orientation and a straightforward public circulation easily accessed from the main entrance can accomplish what no amount of signs can address.

Some design elements are associated with evidence of better outcomes in a variety of areas. For example, single patient rooms, as opposed to semi-private rooms, are associated with improvements in both infection control and reduced patient stress from noise. It is also much easier for a single-patient room design to provide good patient access to natural daylight and views. Because single-patient rooms also typically provide more space for patient's families and avoid having multiple families within a single room, private rooms are now also being studied for better care resulting from more family social interaction.

Whenever multiple proven evidence-based ideas can be combined with thoughtful design, some of the best results can be obtained. For instance, we design our private rooms with distinct family zones that include a bay window with large expanses of glass. The bay window admits lots of daylight, and provides a daybed for family members. A charting vestibule accommodates staff, while limiting noise and interruption for the patient. Architectural elements and artwork introduce color to supplement the views of the natural environment. The resulting room is designed with an eye towards a non-institutional, hotel-like environment – but utilizing elements firmly grounded within evidence-based concepts.

Lessons learned from patient room studies can be applied to the design of the complete patient unit. By carefully reviewing the placement and configuration of waiting rooms and family spaces, families can be accommodated throughout the unit. Studies indicate that arranging the furniture within these spaces in small, flexible groupings increases social support and reduces stress for patient's families. Similarly, design for reducing noise involves not only the patient room, but also the configuration and placement of staff areas.

Nurses stations are a critical location where good design can help deliver better care for patients and reduce noise. Separating the nursing functions into "off-stage" and "on-stage" areas allows each area to be optimally designed for its intended use. "Off-stage" staff areas can be designed with acoustic privacy and bright lighting appropriate for a work environment. "On-stage" areas for public interaction can be designed to assist with wayfinding and family support, while avoiding introducing "working" noise into the patient environment.

Overcoming a shortage of data

One of the frustrations of implementing evidence-based design concepts within a new design can be a lack of data on a particular subject, or the absence of a clear consensus within the available research. Familiarity with the direction of research, however, can offer an opportunity to explore the issue with the project stakeholders to improve the project satisfaction for the owner, regardless of the current state of the research.

For instance, researchers are currently exploring the potential of same-handed rooms to increase staff efficiency and reduce medical errors. While the research does not yet indicate a clear correlation, simply discussing the possibilities with staff in the context of designing and mocking up patient rooms and exam rooms can be a valuable tool to optimize their work environment. The topic can bring with it detailed conversations about how nurses work with their patients, left and right-handed rooms, and the general issue of standardization. Reviewing these ideas with staff will provide valuable insight into their day-to-day routines, even in the absence of a clear evidence-based directive.

The spirit of evidence-based design brings with it more than just a set of "best practices" that can be consulted and copied into a developing design. It creates a lens through which architects and owners can thoughtfully focus on processes that have always been a part of good design. Health care designs should always be grounded not in a designer's personal preference, but rather should be tested against the real-world environment of patient and staff interaction.

Every design benefits from a careful analysis of how a design element will be used by a patient, by a visitor, by a nurse and by a physician. Additionally, following a piece of equipment or supply can provide valuable insight into how a plan will function once in use. Detailed reviews with staff and stakeholders at each phase of design, focusing on each of these things provides a forum for both learning from existing experience and thoughtfully challenging both the designer's and stakeholder's assumptions.

While a full-scale research study may not seem the best fit for many rural facilities, each project provides valuable instruction post occupancy. Reviewing the patient flow with staff allows the opportunity to learn detailed lessons about where design concepts are working well, and where they have changed in a real world environment. These lessons help continually shape new projects to reflect the constantly changing world of medical care.

Michael B. Speck is an architect with Johnson Johnson Crabtree Architects PC, based in Nashville, Tenn. He can be reached at mspeck@jjca.com.