What's it worth?

|

|---|

| Photo by Steve Rasmussen Photography, courtesy of Health Facilities Group Kiowa County Memorial Hospital by the Health Facilities Group achieved LEED Platinum in 2011. |

The U.S. Green Building Council's (USGBC's) Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) remains an emerging idea for many health care organizations, although uncertainties about its cost benefits prevail in a cost-sensitive sector.

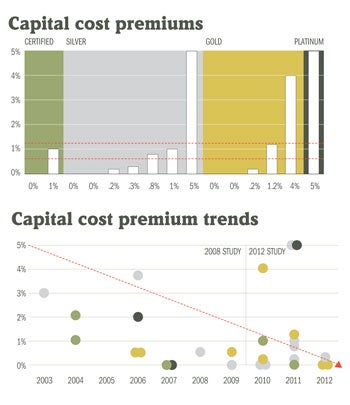

Industry anecdotes have fed misperceptions about the capital cost of LEED-certified hospitals, with some believing that certification can cost upward of 10 to 15 percent more than standard practice. However, a 2012 study conducted by the authors of this article to challenge this thinking titled "LEED Certified Hospitals: Perspectives on Capital Cost Premiums and Operational Benefits" determined that the capital cost premium for LEED-certified hospitals over 100,000 square feet was less than 1 percent.

As health care organizations undertake new design and construction projects, the study's findings provide compelling evidence that LEED certification is a cost-effective endeavor and sound investment that can deliver long-term operational and broader community and public health benefits.

Growth of LEED

Over the past decade, the number of LEED-certified health care buildings has increased in every region of the country. Through the end of 2012, hundreds of health care buildings, including new construction, interior renovations and existing buildings, have achieved LEED certification, varying by type, scale and location.

For new construction projects alone, more than 250 health care buildings have achieved LEED certification, including more than 75 hospitals, according to the Green Building Certification Institute (GBCI). For health care projects pursuing LEED for New Construction (LEED NC), LEED Silver is the most commonly achieved level at 41 percent, followed by LEED Gold at 30 percent, LEED Certified at 27 percent, and LEED Platinum at 2 percent.

The first empirical study on the capital cost of LEED-certified health care buildings was conducted in 2008 by Adele Houghton, AIA; Gail Vittori, LEED Fellow; and Robin Guenther, FAIA. It analyzed 13 LEED-certified projects, including acute care hospitals, outpatient buildings and mixed-use health facilities.

It concluded that capital cost premiums averaged 2.4 percent and were decreasing over time. Another key finding was that projects achieving higher certification levels tended to incorporate LEED earlier in the design process, locating cost synergies and identifying grants and incentives to help reduce the premium.

|

|---|

| Graphics courtesy of Perkins+Will and The Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems Top, the average capital cost premium is 1.24 percent for all 15 hospitals and .67 percent for the 13 hospitals with more than 100,000 square feet. Below, each dot represents one hospital and is color-coded by certification level. |

New study results

Given the large number of certified projects and continued perceptions of increased capital costs, a new study commenced in 2012, again to assess the capital cost premium associated with LEED-certified hospitals.

The research utilized an online survey tool and follow-up phone interviews with individual teams. After completing the survey, conference calls were held to review the results, uncover nuances in the input data and confirm the most accurate way of articulating the LEED capital cost premium for a given project.

The 15 hospitals selected for the study completed their projects between 2010 and 2012 to ensure that they represented the most current data set and associated cost data. Nine design firms had projects represented in the study; design team members from each subject hospital contributed the project cost data for the study.

The hospitals included in the study had wide variation to achieve a representative sampling: the smallest, Kiowa County Memorial Hospital, Greensburg, Kan., is a rural 15-bed, 49,000-square foot critical access hospital; and the largest, Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, is an 830,000-square foot academic medical center with 386 beds.

Beyond size, the projects included low-, mid- and high-rise construction located on sites ranging from rural greenfield to urban in all U.S. regions and climate zones. Together, they totaled more than 5.2 million square feet and represented $3 billion in construction cost. In addition, the hospitals represented Certified, Silver, Gold and Platinum levels, enabling the study to revisit the question about the relationship between capital cost premium and LEED level of achievement, which was also addressed in the 2008 study.

The organization of the survey itself was important. Respondents were asked to select from four commonly used definitions of "capital cost premium" from the 2008 study to correspond to those aligned with their own understanding.

Sixty percent of respondents selected at least two definitions and 50 percent selected three or more that revealed two realities: The industry as a whole does not have a standard definition and there exists inconsistency even within individual project teams. The one definition selected by all respondents was an "increase in the established project budget due to LEED certification."

Projects that incorporated LEED during the design process and did not increase the initial construction budget to accommodate it reported no capital cost premium (5 of the 15 hospitals, or 33 percent). This does not mean that all projects that reported premiums achieved a budget increase; in fact, most did not. It simply means that the methodology for achieving "no identified cost" associated with LEED certification is one that works all the costs into the basis of design.

Despite the lack of uniform definition, the capital cost LEED premiums for the 15 hospitals fell within a fairly narrow range of 0 to 5 percent, the same as in the 2008 study, with an average of 1.24 percent. The two highest premiums were reported by the two smallest hospitals, which raised an important question on economy of scale, although one of those was the only LEED Platinum project represented. Segregating the two hospitals in the data set under 100,000 square feet and calculating the premium only for the 13 hospitals greater than 100,000 square feet yielded an average capital cost premium of .67 percent, with no correlation between the level of LEED certification and premium.

Aggregating the 2012 data set with the 2008 results showed that the 2012 averages — 1.24 percent overall and .67 percent for hospitals over 100,000 square feet — are lower than the 2.4 percent identified in the 2008 study and reflect a downward trend toward cost neutrality over time. However, as each generation of LEED-certified hospitals has raised the bar of performance across many sustainable design indicators, it is unlikely that the capital cost premium ever will be zero, especially when factoring in discrete soft costs.

This continued push for innovation and utilization of new technologies may always necessitate a premium for those projects on the leading edge, although the related operational benefits and return on investment also may increase. Indeed, there is an emerging pattern that shows performance benefits such as reduced water and energy costs offsetting capital cost green premiums over the life of the project.

Hard and soft costs

Individual project costs that contribute to a LEED capital cost premium include both hard and soft costs. Hard costs are the components of construction, building systems, technologies and materials. Soft costs include design and construction team fees as well as GBCI certification fees.

Teams included the full cost of an element in the capital cost premium if it was included purely to achieve a LEED point; otherwise, they included the cost difference between a standard product and the specified item.

This is another arena with very little consistency. Respondents noted that often there was no objective baseline against which to measure the difference, because a team does not design two complete systems for comparison. This is particularly true in electrical and HVAC, for example, and the premium for features such as LED lighting, low-flow plumbing fixtures or energy-efficiency measures.

Data sources were diverse. In some instances, construction managers did calculations. In others, calculations were done by the health care organization, architect or sustainable design consultant. There were little hard data assembled on payback or life-cycle costs.

Respondents cited bicycle storage as the most common hard-cost premium likely because some hospitals include this feature solely to achieve the LEED point regardless of interest in bicycling within their communities. Other commonly cited hard-cost premiums were for components that delivered operational savings, such as optimized energy systems, low-flow plumbing fixtures, high-performance roofing and storm-water management systems.

Beyond these five components, there was little consensus around capital cost premiums included in the calculus — a total of 40 different building components were noted by at least one respondent as constituting a component of the capital cost premium. These included finish materials such as Forest Stewardship Council-certified wood and low-volatile organic compound paint, technologies including carbon dioxide sensors and even operations-based practices like green housekeeping and integrated pest management.

This variability prevents an apples-to-apples comparison from one project to another. Low-flow toilets, for instance, may be tracked as part of the LEED capital cost premium by one project team, but not another. For those project teams that reported and tracked premiums, decisions on which components to include were made by the health care organization or design team, or both. In fact, design firms with multiple projects in the study reported some variability between projects.

There was greater consensus on the soft costs that contributed to a LEED capital cost premium. Respondents identified costs specific to certification, including LEED registration and review fees as well as LEED documentation and management fees paid to the design team, consultants and contractor.

These costs are unique to the LEED certification process; however, respondents also identified energy modeling and commissioning that may be considered best practice today regardless of LEED. In total, these soft costs represented a capital cost premium of .15 to .3 percent for a hospital with less than 100,000 square feet and .1 to .2 percent for a hospital larger than 100,000 square feet.

Value of certification

The analysis addressed the trend toward building to a LEED equivalency without submitting for review or certification.

Considering the third-party due diligence on the design and construction process associated with the LEED review process, the study concludes that the incremental cost of pursuing formal certification is a worthy investment.

Respondents also shared their biggest barriers to controlling LEED capital costs, with three primary reasons conveyed:

• The project team's inexperience with LEED certification, even though most 2012 project teams reported medium to high experience levels.

• Midstream attempts to pursue LEED when it was not included in the original project basis of design and budget but, instead, was added later.

• Evolving LEED goals or LEED overachievement in which the owner mandates a particular certification level at the onset and a higher certification level was achieved. This reflects the growing expertise of design and construction teams and corresponds with a consistent theme articulated by the study respondents: Achieving LEED Silver certification is the cost neutral performance baseline and standard practice for many design and construction firms.

Green building-related grants and incentives decreased significantly from the 2008 study, with only 20 percent of projects in the 2012 cohort receiving any financial assistance. However, this did not appear to have a negative impact on certification.

The value proposition for LEED certification is twofold: the anticipated operational savings and quality benefits in relation to the calculated cost and gaining strategic business and marketing advantages.

Respondents to the 2008 study identified seven key benefits that organizations with LEED-certified facilities hoped to realize. These benefits were ranked by respondents in the 2012 study: Civic leadership was selected as most important followed by occupant health and safety, community benefit, environmental performance, operational efficiency and reduced cost, funding requirements and regulatory requirements.

The rankings reinforce the notion that health care organizations view environmental stewardship as integral to their role in supporting the health of communities. A second key benefit is a business and marketing advantage. Forty percent of responding design firms hoped to gain a competitive edge if their health care client's facility achieved LEED certification.

Beyond the facility site, almost half of the project teams reported benefits to the community and local municipal utility systems, which potentially enhance resilience to extreme weather events. Many hospitals incorporated advanced on-site, stormwater management systems that reduced discharge and treatment costs for their local municipalities.

One of the respondents built a pipeline to a local landfill to harvest methane to then use as thermal energy. The system reduces the emissions for the town, and reduces the energy demand of the local power company while providing the hospital with a carbon neutral energy source.

Respondents relayed the types of operational benefits being tracked by health care organizations, but noted that they typically were not involved in the data collection or analysis. A post-occupancy evaluation can inform the design process by providing a feedback loop; however, only one-third intended to implement such a study.

Eighty percent of the subject hospitals are tracking energy savings and 60 percent are tracking water savings. While reduced utility costs and environmental benefits are not high on the list of desired outcomes, the savings from optimized energy and water systems can be substantial.

A LEED Gold-certified hospital included in the study was designed to reduce energy costs by 20 percent compared with a code-compliant, baseline hospital. If these modeled results are realized during the first 10 years of occupancy, it will equate to $7 million in cost savings and a greenhouse gas reduction equal to the amount of CO2 offset by 37,000 acres of forest.

A continued critique of LEED is the lack of operational data from completed projects and a concern that the modeled savings are not realized in the building's operational phase. These concerns will remain until there are data from operational LEED-certified facilities, and are addressed in LEED 2009 and LEED v4, which include more robust mandatory data reporting requirements.

Significantly fewer hospitals are tracking the health-related benefits; only one-third are measuring impacts to patient recovery times and staff absenteeism. These low engagement rates undoubtedly reflect the difficulty in improved health outcomes-related research, which requires specialized expertise and funding.

Future of certification

The 2012 study shows the capital cost premium of LEED-certified hospitals to be minimal and decreasing over time.

It also shows that the design sector must increase involvement in the collection of both capital cost and operational data from completed facilities to strengthen the value proposition.

Aligned with health care's overarching mission of "do no harm," the study's findings provide compelling evidence that the third-party review and due diligence associated with LEED certification is a cost-effective endeavor and sound investment that can deliver long-term operational and broader community and public health benefits.

Breeze Glazer, LEED AP BD+C, is research knowledge manager and associate, and Robin Guenther, FAIA, LEED AP BD+C, is principal at Perkins+Will, New York City; and Gail Vittori, LEED Fellow, is co-director at the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems, Austin, Texas. They can be contacted at Breeze.Glazer@perkinswill.com, Robin.Guenther@perkinswill.com, and gvittori@cmpbs.org, respectively.

Need more information?

The complete results of the 2012 study were published in the book Sustainable Healthcare Architecture, second edition, by Robin Guenther and Gail Vittori and published in 2013 by John Wiley & Sons Inc. It can be purchased at www.wiley.com or through book retailers.