A three-pronged strategy for energy purchasing

Energy is no longer simply a facilities issue, but is also a financial one. As hospitals must change their operations and planning in response to difficult market conditions, energy supply management must keep pace.

The American Society for Healthcare Engineering’s (ASHE’s) monograph, “Energy Procurement: A Strategic Sourcing How-To Guide,” provides health facilities professionals with the financial knowledge and methods needed to adapt to rapidly evolving energy markets.

Three best practices

Three best practices, known as the “3A’s,” can help to guide health care facilities professionals toward better energy planning:

1. Alignment. For decades, energy traditionally has been the exclusive responsibility of the hospital facility director. Today, changes in the market mean that professionals from other departments, particularly finance and supply chain, also can provide substantial value in energy procurement.

While most facility managers are trained in central energy plant operations, fewer have the requisite financial and contracting skills to negotiate the wide range of energy functions pertinent in today’s environment. These include electricity and fuel purchasing; peak load management and reduction; demand response; temperature controls, backup power generation and resiliency; and renewable energy and environmental offsets.

It is important to analyze and integrate these with each other into a cohesive energy plan by drawing on the skills from around the organization.

Additionally, as hospitals merge to consolidate functions and drive down costs, campuses are being repurposed. This means that the energy assets and operations of these facilities must change subject to new systemwide strategic plans.

In this complex and rapidly changing environment, the best way to obtain the expertise and support necessary for a strong energy-management program is to form a cross-functional team that brings together the expertise of several disciplines within the health system. When seeking the participation of the various members of the energy committee, consider the following guidelines:

• The facilities department has specific knowledge of the hospital’s energy needs, including usage and anticipated changes in demand. This information will be crucial when deciding how to layer energy purchases over the life of the contract. Facilities staff will provide information regarding the relationship between market energy and on-site operations.

• Corporate treasury and finance manages all of the institution’s investments, including products traded in financial markets. Because energy also is traded in a financial market, it is vitally important to recruit finance to share its expertise in this area. Establishing a working relationship with finance will become increasingly important as the facility professional considers a wide range of energy-related projects, such as equipment upgrades.

• Supply chain and purchasing bring to the committee an in-depth knowledge of contracting practices. Because energy contracts can be detailed, it is vital to have contracting expertise on the team when negotiating terms and conditions.

2. Analytics. The key to a hospital’s success in navigating the energy markets is to view the procurement budget as a financial investment. This means employing the same kind of analytics and risk-management tools used to manage the hospital’s insurance risk or its treasury portfolio.

When undertaking the energy-procurement process, the energy committee should first ask which criterion is most important to the hospital in setting its energy-procurement goals. Criteria for consideration include:

- How important is it to obtain the lowest possible cost of energy, which may increase risk?

- How important is budget stability, which can mean paying a higher premium?

- Are we willing to balance low cost and budget stability?

- How much energy does the hospital need to buy over the next five years?

- How likely is the hospital to modify campus operations and change the energy load?

- How likely is the hospital to generate its own electricity within the contract period?

When purchasing energy from the local utility, a buyer is subject to whatever rate changes the utility may impose, usually on a quarterly or annual basis. When buying directly from the market, a buyer may set its natural gas rates for up to three years and electricity rates for up to five years in advance. In addition, the buyer may set a fixed rate, pay the prevailing market index rate or choose some combination of both.

A fixed rate is a firm contract price for a fixed amount of energy for a fixed duration of time agreed upon by the buyer and supplier. This rate is referred to as fixed but, in practice, nearly all energy supply contracts allow the supplier to pass through certain non-energy costs or cost changes, resulting in actual prices that are only partially fixed.

A market index rate refers to the price of energy at a particular delivery point at the time the energy is consumed. For electricity, index rates float on an hourly basis, while for natural gas they could change monthly or daily, depending on the contract.

Most hospital buyers traditionally have chosen a fully fixed rate for energy because they perceive that budget stability is vitally important and because they see no value in increasing budget risk to achieve potential savings. However, as health care organizations become larger or as they aggregate with one another in various group purchasing organizations (GPOs), the opportunities for managing upside risk while seizing real cost-reduction opportunities are significant.

Similarly, many energy buyers, having grown accustomed to years of declining energy prices, have concluded that simply buying at the floating market index rate is the best strategy and least costly approach over time. But, this method also exposes the buyer to significant risks from short-term fluctuations and price run-ups.

For many hospitals, a hybrid approach known as dollar-cost averaging can yield the best results. In this approach, the hospital buys a percentage of its future energy requirements at a fixed rate, but leaves open the option of setting the price for the balance of the load at a later time. By carefully watching the market and using financial analytics to assess market movements, the hospital can obtain both budget stability and lower pricing [see sidebar, Page 26].

Ultimately, the energy committee must examine the value of the relationship between cost and risk to its organization, and must design its portfolio of energy investments to match those values.

3. Aggregation. Because energy is financial, larger aggregations of energy spend are attractive to the market. The benefits of larger aggregations include lower supplier margins and access to the best products, pricing and contracts available.

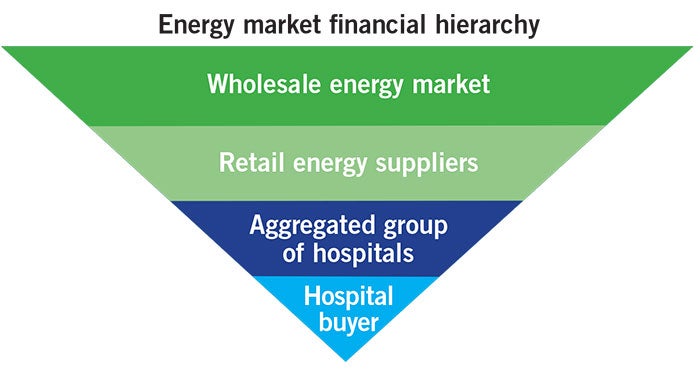

The energy market financial hierarchy — ranked from most dominant to least dominant — includes the following players:

- Wholesale energy market. Financial institutions such as JP Morgan Chase & Co. and Deutsche Bank, as well as global energy giants, dominate the wholesale market and trade billions of dollars in energy each day. These institutions use financial agreements to set pricing.

- Retail energy suppliers. Retail suppliers enter into financial transactions with wholesale trading operations to set a price for a specific quantity of energy. The supplier adds its profit margin onto each unit of electricity or natural gas delivered to and consumed by the hospital pursuant to the retail supply agreement. Retail supplier margins generally are no more than 3 percent of the total cost of energy.

- Aggregated groups of hospitals. Aggregations of individual buyers are attractive to suppliers and induce suppliers to provide lower cost access to the wholesale market and to better products and contract terms.

- Hospital buyers. Individual buyers are at the bottom of the energy market hierarchy and typically buy higher-cost, fixed-rate contracts from retail suppliers.

A paradigm shift in energy procurement for hospitals began in 2010, when the nation’s leading health care GPOs demanded changes from the energy supply market. Not only were hospitals searching for lower costs, but they also began to demand the financial management tools that previously were available only to large corporate buyers.

As hospital GPOs aggregated their members’ energy spending, group buying power increased significantly, soon totaling tens and even hundreds of millions of dollars. At the same time, massive cost reductions triggered a rapid consolidation in the hospital sector, resulting in the consolidation of multiple facilities into large integrated delivery networks (IDNs).

This increased scale has helped to drive down supplier margins, by as much as 50 percent in many cases, without the need for auctions. Most importantly, suppliers are now offering GPO members, large IDNs and, increasingly, single hospitals the same financial management products that previously had been reserved for only the large corporate elite.

Health care energy buyers are strongly encouraged to seek collaborative arrangements with their peer institutions to obtain the benefits of energy aggregation.

A financial issue

Implementing these best practices provides hospital facilities professionals with the approach, knowledge and methods needed to adapt to evolving energy markets and manage energy spend.

Facilities professionals should advocate for internal alignment, making allies of supply chain and finance to benefit from their expertise. Then, professional financial analytics will allow for informed decision-making and execution of strategic plans. And, finally, aggregation helps hospitals to drive down supplier costs, obtain access to optimal contract terms and benefit from peer review by colleagues at other hospitals.

By following these practices, facilities professionals not only will drive greater budget savings, but also prepare their hospitals for the next era of campus energy management. HFM

Mark Mininberg is president of Hospital Energy, Elmhurst, Ill., and co-author of the ASHE monograph, “Energy Procurement: A Strategic Sourcing How-To Guide.” He can be contacted at mark@hospitalenergy.com.