Building a continuity of operations plan

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasizes the importance of continuity of operations planning.

Image by Getty Images

At the time of this writing, there had been 9,832 COVID-19 cases among health care workers, including 723 hospitalizations, with 184 in intensive care units and 27 deaths. Looking at the world from the (hopefully) far side of the COVID-19 pandemic puts an entirely new focus on health care emergency planning.

True, most hospitals have had few emergency management (EM) findings during accreditation surveys; and emergency operations plans (EOPs) have been written, for the most part, to the appropriate accreditation requirements, with varying degrees of compliance.

Those plans got facilities professionals past surveys, but did they effectively get their organizations through COVID? The health care field has work to do on emergency management. Though this is purely conjecture, it’s also likely that there will be major changes to the standards going forward, based on lessons learned.

This article focuses on the continuity of operations plan (COOP) as the standards are currently written.

Considering a COOP

The COVID-19 pandemic certainly has given facilities professionals pause to consider continuity of operations. Given the statistics on infection of health care workers, many hospitals needed to continue functioning with less than a full complement of staff members.

Undoubtedly, some of these absences required placing others in acting leadership positions. Perhaps in some cases this was anticipated and planned for, but in many organizations, it may not have been considered prior to the need.

There is a lot of justification for a COOP throughout various regulatory documents. The 2019 edition of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 1600, Standard on Continuity, Emergency, and Crisis Management, defines continuity as, “A term that includes business continuity/continuity of operations (COOP), operational continuity, succession planning, continuity of government (COG), which support the resilience of the entity.”

The Joint Commission (TJC) defines COOP in EM.02.01.01 EP 12, as “A continuity of operations strategy focuses on the organization, with the goal of protecting the organization’s physical plant, information technology (IT) systems, business and financial operations, and other infrastructure from direct disruption or damage so that it can continue to function throughout or shortly after an emergency. When the organization itself becomes, or is at risk of becoming, a victim of an emergency (power failure, fire, flood, bomb threat and so forth), it is the continuity of operations strategy that provides the resilience to respond and recover.”

The 2012 edition of NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, includes continuity of operations as one item to be considered in the hazard vulnerability analysis. Section A.12.5.1.3(1) states, “Continuity of operations can include, but is not limited to, maintaining staffing levels, resources and assets, ability to obtain support from the outside environment, and leadership sustainability.” (This language remains intact through the 2018 edition of NFPA 99.) DNV defers to the language of NFPA 99. And the 2014 edition of the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) includes a business continuity branch in the “operations” section.

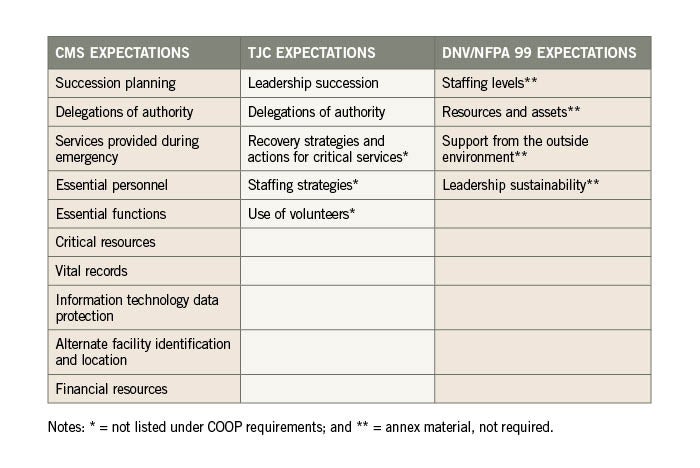

But the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, TJC and DNV NAIHO® accreditation requirements differ significantly in their specific COOP expectations. The table above provides a listing of those requirements. However, TJC also adds COOP-related requirements at EM.02.01.01 EP 4, recovery strategies and actions for critical services, and EM.02.02.07 EP 14, emergency staffing strategies and the use of volunteers.

The author recommends that facilities professionals build their COOP based on the more comprehensive of the requirements, knowing that this may exceed the requirements of the organization’s accrediting agency. Doing so enhances the organization’s readiness for whatever emergency may occur, including a global pandemic.

A suggested list of items to consider includes leadership succession (i.e., hospital leadership and departmental leadership), delegation of authority, business impact analysis, recovery time objectives, financial resources, staffing continuity, resource continuity, alternate locations, preservation of records and similar components.

To get started building a better COOP, facilities professionals should assemble a multidisciplinary team from across the organization, being sure to include appropriate stakeholders and a leadership sponsor. Membership should include clinical and support services.

This team should begin by setting goals. Suggested goals include provision of service continuity, facilitation of timely decision making, minimization of transition disruptions and facilitation of return to normalcy.

Beyond the longer list of topics to address mentioned previously, facilities professionals should start by looking at leadership succession on an organizational level. This will involve fewer positions to consider, and perhaps the framework of leadership succession is already in place. Not all organizations choose to share leadership succession plans publicly. If that is the case, the important thing to know is that the plans exist and who has the ability to access them.

If the plans are not already in place, they need to be formulated by the COOP team, with appropriate consideration of current leadership recommendations, skill sets and any other circumstances. Leadership succession plans are implemented when key members of the leadership team are unable to assume their roles. Advance planning expedites the process and should be completed for at least all members of the C-suite. It is recommended that leadership succession plans are at least two to three deep, including the incumbent in the position.

Some health care organizations have interpreted leadership succession to reflect the change of leadership in the HICS command staff over various operational periods in the management of an event. Those transfers of leadership are well-established in the HICS documentation and should also be planned at least three deep. While they are necessary for managing through an emergency situation, the changes in HICS leadership do not fully address the absence of an organization leader for a period of time or permanently.

Once leadership succession plans are formulated for organization leadership, it is appropriate to consider department leadership succession as well, again noting that this portion of the COOP is not necessarily required by specific accreditation agencies. Departmental succession plans would identify and groom others for leadership positions in the event of an emergency.

For example, a charge nurse might be chosen to succeed the department director or manager. Those individuals in the line of department leadership succession should be provided with appropriate training so that they can easily transition into a more senior position within the department, should it be necessary. (Planning for department leadership succession also can be viewed as a career ladder.)

Department leadership succession plans can be managed in a variety of ways. One method is to develop a listing of leadership positions in each department with key characteristics and requirements of those positions. This can be developed into a worksheet to be completed by each department head, with suggestions of individuals who would be likely candidates to fill those roles. In addition, training requirements can be added. Alternatively, group interviews could be conducted with leadership from similar departments to identify the roles and responsibilities that would need to be filled if a leader is absent.

Delegations of authority is the other requirement found in most accreditation requirements. These delegations should be specified in the succession plans and grant authority for individuals being moved into these assumed roles as necessary during an emergency. There may be legal considerations for some of the roles, and it is appropriate to seek guidance from the organization’s risk manager and/or legal counsel in the planning process.

The delegations should be linked to the assumed positions and may include items such as the authority to evacuate the hospital, represent the organization to various government entities and activations of memoranda of understanding. Triggers for activation of delegated authority should also be included in the plan, such as safety concerns, unavailability of leaders and others.

Tools to determine business impact analysis and recovery time objectives are keys to understanding recovery strategies and actions for critical services, as required by TJC, but not under the COOP banner (see the table on page 39 and the sidebar on this page).

Based on these considerations, recovery considerations and actions can fall into a variety of categories that need to be considered to continue operations through a recovery period:

Staffing. This must include communication with staff who are on and off duty. Staffing continuity throughout the event is critical, with thought given to minimum acceptable staffing, potential consolidation of departments, use of temporary or contract staff, and the use of volunteers.

Resources. Memoranda of understanding that have been negotiated must be current and available. They should be tested as part of emergency exercises. The organization should not rely on a single-source provider. (No guarantees can be expected of MOUs, for example when all hospitals needed large quantities of masks for COVID-19.) Ninety-six hour sustainability must be well understood as a ballpark number based on normal usage. But that sustainability must be calculated and not dependent only on a list of items in the inventory.

Records storage and protection. Records for emergency operations, business, corporate functions, finance, financial donors and IT must be maintained and protected. Facilities professionals should determine for all records storage locations, format(s) of the data (i.e., electronic or hard copy), and availability of mobile access or remote backup. Frequency of IT backups should be understood as well as how backup data can be accessed, such as through other system computers, a hot site or other means.

Alternate care sites. Remember that alternate care sites can be internal to a hospital building; they just might not normally be used for patient care. These sites may be used for relocation of services, overflow or staging areas. Patient care also may be relocated to temporary sites. Professionals have collectively seen lots of this during COVID-19, but they should document what worked well into the COOP.

Financial resources. Obvious planning considerations should include accounts payable, available credit and staff payroll. Additionally, facilities professionals should consider the potential for needed staff assistance, and the availability of cash, in the event that automatic teller machines are not functioning. Again, many of these were seen during COVID-19, and provided experiences for future planning.

Reconstitution. Eventually, an event will be over, as is hoped now for COVID-19. The plan then shifts from continuity of operations to restoration of operations. Critical planning includes ensuring the safety of the facility and planning for reentry, if there was an evacuation or damage to the building. Supplies must be replenished prior to reopening the facility and returning to full provision of patient care and services. All of these activities must be communicated to the staff and the community, with regular progress updates.

Truly sustainable

There is much more to COOP than leadership succession and delegation of authority. Following this process using a multidisciplinary team headed by a leadership champion, coupled with patience and perseverance, can lead to a health care organization that is truly sustainable, whatever may befall it.

Susan McLaughlin, FASHE, CHFM, CHSP, is chief operating officer at MSL Healthcare Partners Inc., Barrington, Ill. She can reached at smclaughlin@mslhealthcare.com.

ABOUT THIS ARTICLE: This article is based on a presentation given at the American Society for Health Care Engineering's 2019 Annual Conference & Technical Exhibition.