New frameworks help to redefine health care violence prevention

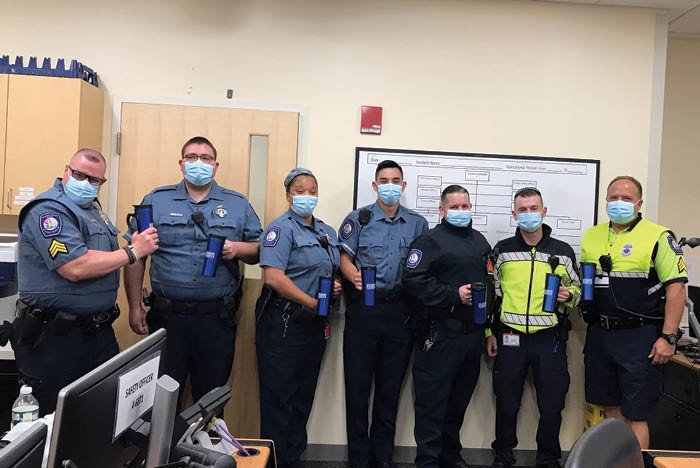

Members of the Boston Medical Center security team during IAHSS Public Safety Week.

Image courtesy of Boston Medical Center

The health care field is determined to take action on workplace violence challenges through better tools to strengthen a proactive approach to violence prevention and de-escalating potential risks earlier.

Among those tools are The Joint Commission’s (TJC) new and revised workplace violence prevention standards for accredited hospitals and critical access hospitals, which took effect Jan. 1, and a guide from the American Hospital Association (AHA) in partnership with the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) on mitigating workplace violence, which can be accessed at aha.org/workplace-violence. Each aims to provide a framework to support hospitals in developing effective workplace violence prevention systems.

Before examining the framework, however, Robyn Begley, DNP, R.N., NEA-BC, FAAN, CEO of the American Organization for Nursing Leadership and chief nursing officer and senior vice president of workforce for AHA, advises that health care leaders must redefine workplace violence.

“In the past, when we thought about workplace violence, it was physical violence in nature, but that definition has really been expanded,” she says. “It goes from incivility on one end of the spectrum to those things we think of as incidents of mass violence, like shootings, on the other end.”

Adopting a broader definition of violence encourages health care professionals to reduce their tolerance for disrespectful treatment and de-escalate situations earlier, before they become dangerous. However, Constance Packard, CHPA, senior director and chief public safety at Boston Medical Center and IAHSS president-elect, notes that pandemic-induced staffing shortages have made critical face-to-face de-escalation training a challenge.

“[It] can be an issue with their schedules,” she says. “But we work our best on giving them the tools they will need to be proactive and not only reactive.”

Brendan Riley, CHPA, director of security for parking and transportation at Lahey Hospital & Medical Center and IAHSS workplace violence prevention subject matter expert, sees this challenge playing out across health care.

“Competing priorities have made it difficult for health care organizations to focus on workplace violence prevention with any consistency, even while experiencing a significant uptick in incivility, aggression and even assaults,” he says.

That’s where Riley sees TJC’s new elements of performance (EP) as a valuable framework for helping organizations reorganize violence prevention efforts. However, Riley predicts that most health care organizations will need to revise their workplace violence prevention programs to ensure compliance with the new EPs.

“Much of the training and education that has been in place does not cover all four areas of focus outlined in [TJC’s}Standard HR.01.05.03, EP 29,” he says. “Additionally, an annual worksite analysis specific to workplace violence prevention is a new process for many organizations. Many organizations identify risks through this process already but have not necessarily tracked the resulting mitigation strategies and changes to policies, procedures, training and education, and updates to the existing environmental design that result from the worksite analysis findings.”

Riley and Packard offer several tips to help health care safety teams begin to audit their workplace violence programs to ensure TJC compliance, including:

- Ensure a comprehensive workplace violence prevention policy is in place and up to date.

- Designate an individual leader for the workplace violence prevention committee, in compliance with TJC Standard LD.03.01.01.

- Reevaluate the committee’s multidisciplinary team to ensure all key stakeholders are represented, with a blend of leadership and staff to include evening, night and weekend shift representation.

- Have executive-level sponsorship of the program, with any program updates communicated to the entire workforce by the CEO.

In taking a bigger stance on violence prevention, these experts also encourage health care professionals to think more broadly about violence beyond their walls.