Comprehensive emergency management programs

Image from Getty Images

The needs of patients do not cease when hospitals are impacted during a disaster or emergency, and hospitals are tasked with continuing to provide care in situations when it becomes much more difficult to do so. Not only that, but many hospitals receive an extra surge of patients seeking care during a disaster.

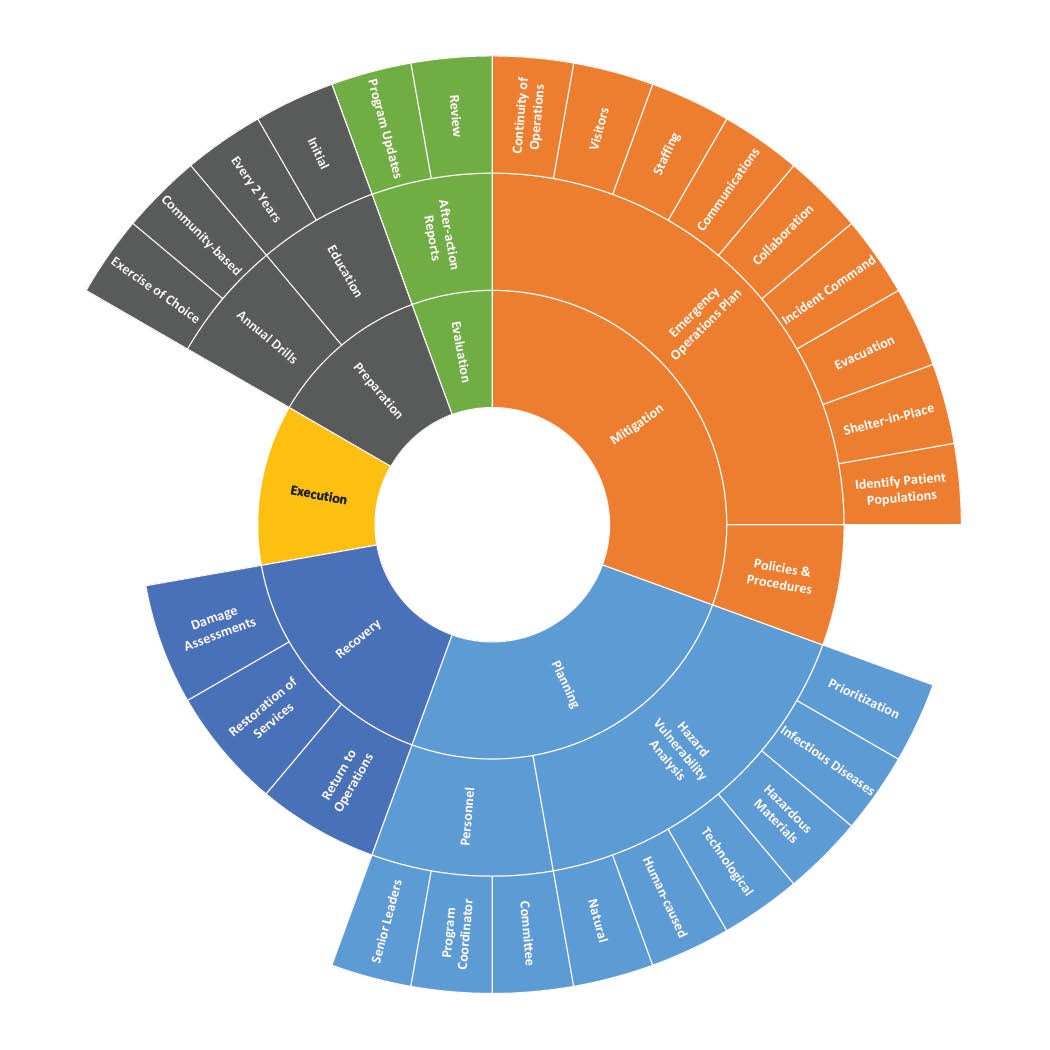

While successful execution of an emergency operations plan is the goal, it takes careful planning, preparation and practice to get it right. The tasks accomplished during normal day-to-day operations will put health care facilities in a position to be able to successfully handle emergencies as they occur.

The role of facilities managers in these preparations is key. They are tasked with providing safe environments, dependable critical utilities and staff that can respond to facility needs as they arise.

Regulatory organizations such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and state licensing agencies as well as accrediting organizations such as The Joint Commission (TJC), DNV and others periodically survey hospital emergency management programs to evaluate whether they are prepared to meet the needs of patients and staff during an emergency. The expectations for organizations have recently been updated.

EM chapter update

On July 1, 2022, the updates to TJC’s emergency management chapter in the Comprehensive Accreditation Manuals for hospitals and critical access hospitals took effect. The standards revisions resulted in a rewrite of the chapter, with many existing requirements remaining and new requirements added, putting greater emphasis on the development and use of a hazard vulnerability analysis (HVA) and increased focus on leadership participation and oversight. The rewrite included a renumbering of the standards, which now begin with standard EM.09.01.01 and end with standard EM.17.01.01.

“The EM program provides an organized, systemic approach in our planning and decision-making to make certain that the hospital is prepared to meet the health, safety and security of its patients, staff and community before, during or after an emergency or disaster,” notes Angela Murray, project director in the department of standards and survey methods at TJC.

Marisa Voelkel, physical environment specialist with the standards interpretation group at TJC, who worked on the chapter rewrite together with Murray, adds that, “one of the things that we decided to do with the revision of the emergency management chapter was to make the flow of the standards more useful for organizations — beginning with the emergency management program structure, tying in leadership and moving through the evaluation of the program.”

TJC’s standards are based upon CMS’s “Emergency Preparedness Interpretive Guidelines,” found in Appendix Z of the State Operations Manual. Appendix Z was last updated on April 16, 2021, and serves as the surveyor guidance for all provider types. The guidance is organized into E-tags, many of which are applicable to hospitals (§482.15) and critical access hospitals (§485.625).

TJC has crosswalked these applicable E-tags with their new standards to make sure all requirements (which organizations participating in CMS’s programs are subject to) are met. Appendix Z provides commentary on each of the E-tags, which is helpful for organizations to understand the rationale behind each emergency management requirement, and how it will be surveyed by CMS or any accrediting organization. Those responsible for emergency management activities for a health care organization are encouraged to review Appendix Z comprehensively in addition to TJC’s EM standards.

Another useful reference is Chapter 12 of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code. While excluded from the official adoption of NFPA 99-2012 by CMS, Chapter 12 provides additional context on a comprehensive emergency management program “to assess, mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from emergencies of any origin.”

‘All-hazards’ approach

The goal of the emergency management program is to take a comprehensive approach to meet the needs of staff and patient populations during an emergency or disaster situation. This involves working together with other health care facilities as well as the whole community that it serves.

Some jurisdictions have specific laws and/or regulations related to emergency management that must be met. As part of its planning, organizations are to take an “all-hazards” approach, meaning they must evaluate the types of emergencies they are subject to and organize planning and mitigation activities around these hazards.

Senior leaders are expected to take an active role in emergency management planning, providing the required resources to develop and support the program and appointing a program coordinator, who must be a qualified individual. While no prescriptive requirements exist for the program coordinator, leaders should consider education, training, experience and certifications, and these organization-specific requirements should be included in the job description for the program coordinator.

The program must be led by a multidisciplinary committee that could include staff from “senior leadership, nursing services, medical staff, pharmacy services, infection prevention and control, facilities engineering, security and information technology.” The goal is to have a variety of diverse viewpoints represented on the committee.

Identifying hazard vulnerability. In CMS tag E-0006, there is a requirement that the emergency plan is based on “a documented, facility-based and community-based risk assessment, utilizing an all-hazards approach.” CMS uses the term “risk assessment,” but Appendix Z states that HVA is a type of risk assessment commonly used in the health care field.

TJC’s standard EM.11.01.01 clarifies its expectations for this HVA. It must consider the hospital’s geographic location, community, facility and patient population. Each facility must have its own HVA because the risks vary among facilities.

Risks may include, but are not limited to, natural hazards (e.g., flooding or wildfires), human-caused hazards (e.g., bomb threats or cybercrimes), technological hazards (e.g., utility or information technology outages), hazardous materials (e.g., radiological, nuclear and chemical), and emerging infectious diseases (e.g., Ebola virus, Zika virus and SARS-CoV-2). The HVA should be a living document that is updated as conditions change.

Organizations are then tasked with prioritizing the results of the HVA, considering the likelihood that the event is to occur and the severity of the risk. The same type of event may have a bigger impact in one location than another.

For example, an ice and snow storm in Texas is very different than an ice and snow storm in Michigan. The storm in Texas is much more likely to impact the operations of a hospital and its ability to provide services due to it not being a common event. The prioritized results of the HVA must be used to determine mitigation priorities and preparation activities, including emergency drills.

Emergency operations plan (EOP). The EOP is another living document (updated at least every two years) that “provides guidance to staff, volunteers, physicians and other licensed practitioners on actions to take during emergency or disaster incidents.” TJC’s standard EM.12.01.01, EP 1, has a list of 11 key components that must be addressed in the EOP and its supporting policies and procedures.

The EOP must identify the patient population of each facility and address persons at risk in the facility or the community in which it serves. It must address when and how the organization will shelter in place, and when and how it would evacuate if necessary. Essential needs, such as food, water, medical and pharmaceutical supplies, and medical oxygen, must also be addressed.

Organizations must describe their incident command structure and operations, noting specifically those with authority to implement the EOP, the structure of the incident command, and primary and alternate locations for the incident command center.

Lastly, the EOP “includes a process for cooperation and collaboration with local, tribal, regional, state, and federal emergency preparedness officials’ efforts to maintain an integrated response during a disaster or emergency situation,” as well as identifying 1135 waiver procedures, which allow organizations to provide care and treatment and alternate care sites.

Communications, staffing and visitors. The communication plan must include names and contact information for staff, entities providing services under arrangement, patients’ physicians, other facilities and volunteers. It must describe primary and secondary procedures for how it will establish and maintain coordinated information to them (and other entities) during an emergency or disaster event, including warning and notification alerts.

It must also address how the hospital will communicate with relevant authorities on its needs, available capacity and ability to assist if called upon. In the event a patient needs to be transferred or evacuated, the plan addresses how the hospital will share information and medical documentation to other providers, as well as how the hospital will track these patients. If there is a surge of unidentified or deceased patients, the hospital must communicate with the local medical examiner’s office, local mortuary services, or other regional or state services.

During an emergency or disaster incident, or during a patient surge, staff and sometimes volunteers are still needed to care for patients. The hospital must develop a staffing plan that addresses how it will contact those care providers, how it will acquire providers from its other facilities (if applicable), and how it plans to utilize volunteer staffing, staffing agencies and the like to support its staffing needs. If volunteer licensed independent practitioners are utilized, their identities and licensures must be verified.

The staffing plan addresses these requirements and defines the extent to which volunteer practitioners may be utilized in the facility, and identifies the individual who is responsible and the process to grant disaster privileges. If the hospital provides its staff to other facilities, it must track the name and location of where they are relocated. Organizations are also expected to address in the staffing plan how they will provide employee support, such as housing, child care, and mental health and wellness needs, during an emergency response.

The emergency operations plan must address how the organization will manage visitors to the facility who are not in need of medical care. The hospital must also have a plan for safety and security measures that describes the role community security agencies, such as law enforcement or the military, have in an emergency event and how the hospital will coordinate security with these agencies.

Continuity of operations. Hospitals are typically expected to maintain operations before, during and after a disaster or emergency event. This requires advance planning and preparation to ensure it has the resources and assets it needs. That is not to say that it needs to stockpile supplies. However, the plan does need to describe in writing how it will document, track, monitor and locate things like medications, medical supplies, medical gases, potable and nonpotable water, food, lab equipment, personal protective equipment, fuel and other nonmedical supplies and equipment.

These resources may need to be obtained from other sources, replenished or conserved, and the plan needs to address how that will occur if required. Based on current resource consumption, the plan needs to describe the actions it will take to sustain its needs for up to 96 hours.

Similarly, the hospital is expected to maintain essential utilities that are needed to provide safe care, treatment and services. These typically include electrical distribution; emergency power; elevators; heating, ventilation and air conditioning; plumbing and steam boilers; medical gas and vacuum systems; and network communication systems. A written plan for how they will be maintained is required.

Some utilities, such as water and emergency power (including generators and fuel) are required to have an alternate source identified. An emergency power source is needed for maintaining safe temperatures in a facility, emergency lighting, fire detection, extinguishing, fire alarm systems, and sewage waste and disposal. Generators used for emergency power must be in safe areas and be inspected and tested at weekly, monthly, annual and triennial intervals.

Hospital leaders are expected to develop a continuity of operations plan that identifies and prioritizes services and functions that are considered essential for maintaining operations. The plan needs to identify alternate locations for providing essential functions during an emergency or disaster event.

Transfer agreements with other entities, or memorandums of understanding, may be needed to secure these arrangements. Leaders may also choose to implement telework or telehealth if physical facilities are not available or are not the best option. They must also develop succession plans that identify who is authorized to step into a particular leadership or management role if a current leader is unable to perform their duties.

Disaster recovery. A disaster recovery plan is needed that describes how and when the hospital will conduct damage assessments, restore critical systems and essential services, and return to operations. The plan must also address coordination with local community partners to locate and assist with identification of adults and unaccompanied children so that they may be reunited with their families.

Training and drills. Staff are expected to be trained on the EOP (including emergency response policies and procedures), the HVA and the communication plan, both at the time of their initial hire and at least every two years after that. This training must extend to “individuals providing services under arrangement and volunteers, consistent with their expected roles.” Individuals with responsibilities identified in the incident command structure must be trained specifically for their duties.

Based on the priorities identified by the HVA, hospitals are expected to conduct annual tests of their emergency operations plan. These drills need to simulate likely emergencies or disaster scenarios, and staff are expected to follow the policies and procedures identified by the organization. After-action reports that identify strengths, weaknesses and opportunities should address all six critical areas: communication, resources and assets, staffing, patient care activities, utilities, and safety and security.

These after-action reports are then evaluated by the multidisciplinary emergency management committee and senior leaders of the hospital, and the lessons learned applied to updates of the emergency preparedness plan, which must occur at least every two years.

Some hospital EM references

Regulatory organizations have provided the framework for the establishment of a comprehensive emergency management program in the form of standards and Conditions of Participation. These resources provide additional requirements as well as important context. They also offer organizations a glimpse into how a surveyor might evaluate a facility’s emergency management program. They include:

- The Joint Commission’s (TJC’s) Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for hospitals or critical access hospitals, emergency management chapter (July 1, 2022, update).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) SC-17-29 “Emergency Preparedness Interpretive Guidelines,” Appendix Z (interpretive guidance; last updated April 16, 2021 [QSO-21-15-ALL]).

- National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, 2012 edition, Chapter 12 on emergency management.

While Chapter 12 of NFPA 99-2012 was excluded when CMS officially adopted the document in its regulations on July 5, 2016, it provides good context and guidance for organizations developing and improving their emergency management programs.

TJC has made available resources on its website, including a crosswalk of the old emergency management standards to the new and a series of videos that address key points regarding the changes. For more information, visit The Joint Commission's Emergency Management page.

Building a hospital EM team

Each person who works in a health care facility serves a unique need in services to patients and staff. By including a diverse group of committee members on an emergency management team reflecting each of these services, facilities professionals will ensure that any unique needs arising during emergencies that others may not consider are identified in advance and mitigated appropriately.

NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, 2012 edition, offers some guidance on the makeup of the emergency management committee:

“12.2.3* Emergency Management Committee.

The emergency management committee shall include representatives of senior management and clinical and support services.

12.2.3.1

The membership of the emergency management committee shall include a chairperson, the emergency program coordinator, a member of senior management, nursing, and representatives from key areas within the organization, such as physicians, infection control, facilities engineering, safety/industrial hygiene, security, and other key individuals.”

People who are hardwired to recognize and deal with dangers make excellent contributors to emergency management activities. And certain professions, in addition to health care, tend to attract people with these qualities, such as former first responders or military personnel. Also, those with a personal interest in disaster preparation may make good contributors.

Leah Hummel, AIA, CHFM, CHC, is senior associate director of advocacy for the American Society for Health Care Engineering. She can be reached at lhummel@aha.org.