Planning for inclusivity in health care facilities

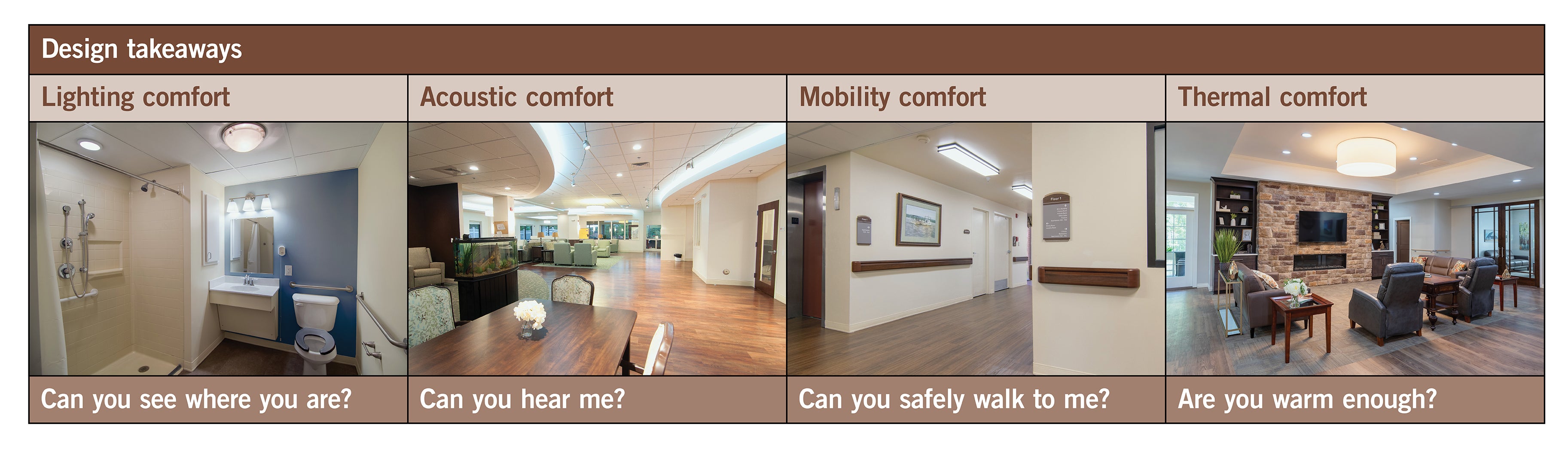

Inclusive design elements on display at the Edward N. and Della L. Thome Adult and Senior Care Center on the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Campus in Baltimore.

Design and photo by JSR Associates Inc.; project by JSR Associates Inc. for Easter Seals

A majority of those seeking care in hospitals and outpatient facilities today are patients over 65 years of age. Because of the shortness of typical patient stays or visits in these settings, the focus is usually on the patients’ reasons for being there — their diagnoses. However, to achieve a better experience for patients, designers are encouraged to evaluate the demographics of those using these settings. The insights gained can lead to designs that support inclusivity and equity for facility users (including staff) of all ages and abilities.

Planning for an inclusive environment starts with understanding who is being served and who is providing care. Because the Facility Guidelines Institute’s Guidelines for Design and Construction of Residential Health, Care, and Support Facilities (the Residential Guidelines) is predominantly focused on settings where older adults and vulnerable populations receive care and services as residents, patients or participants, design that supports inclusivity and equity has been a part of the document since it first became a stand-alone Guidelines publication in 2014. Therefore, when considering how best to serve the largest population of hospital and outpatient patients today, health care facility designers can lean on lessons learned from the application of the Residential Guidelines.

Person-centered care

The approach to facility design in the Residential Guidelines reflects a change in focus in the long-term care field from an institutional model to a person-centered care approach. This encourages looking beyond a diagnosis to see the care recipient as a whole person who happens to need help coordinating and accessing various levels of care and services.

This understanding can be leveraged by evaluating space from a service, access and enjoyment perspective that reflects individual likes and dislikes, activity preferences that include fun and enjoyment, staff understanding of a care recipient’s background and history, and all the beautiful pieces and parts that make an individual unique.

The residents, patients and participants who use the facilities included in the Residential Guidelines can be any age, ranging from children to young adults who may have developmental or intellectual disabilities, to mature adults who may have early onset dementia or a temporary rehabilitation need, to older adults from ages 55 to 105 or more.

The person-centered care approach also extends to staff members, who are often considered part of a resident’s or patient’s extended family, and to an individual’s family members who are also caregivers. With health care staff aging and usually at least one older family member accompanying a patient, everyone can benefit from inclusive planning, design and details that support individuals of all ages and abilities.

There are opportunities at every stage of design to improve the physical environment for patients, staff and family: the functional programming process when desired outcomes and care delivery issues are identified, development of owner project requirements, and creation of design details that support older adults and the temporarily vulnerable in the built environment.

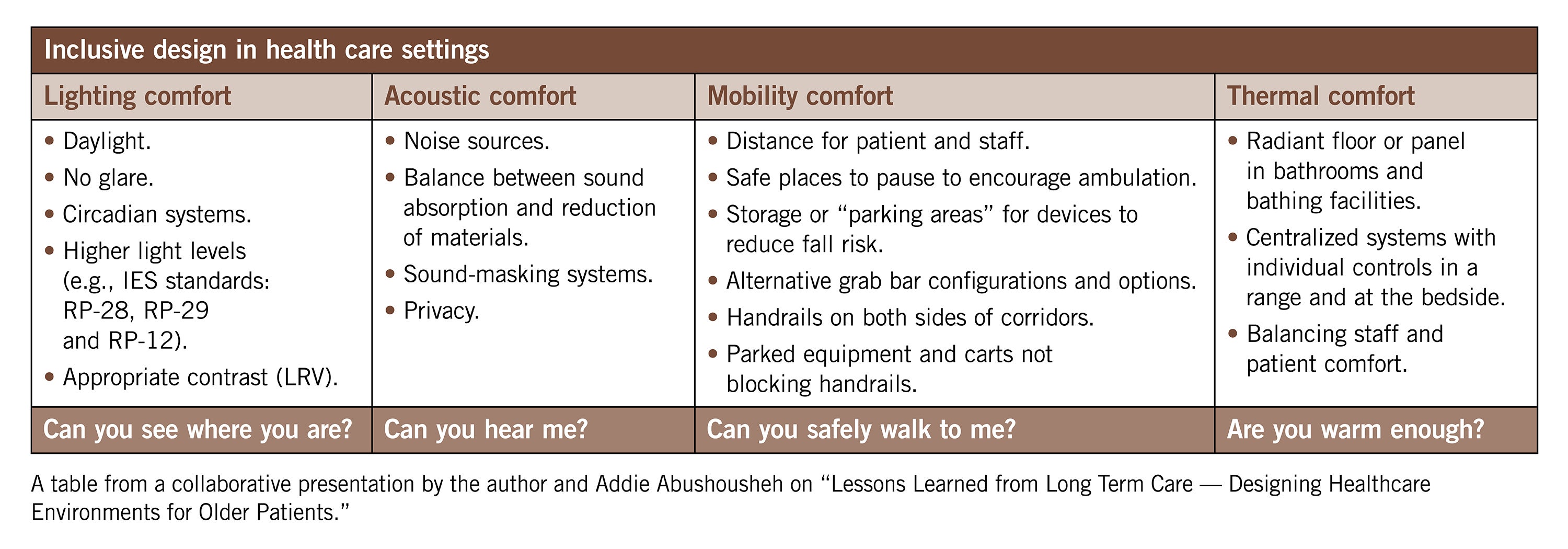

The four comforts

Four areas of consideration for designing for older patients in outpatient and acute care settings help drive product selection through person-centered attributes. In evaluating these four areas through the overlay of older patient, staff and visitor needs, a design can be improved to support vulnerable populations of all ages and abilities.

The table on this page highlights the functional programming questions that each comfort addresses. Are lighting levels high enough so a patient can see where they are within a space? Do the acoustics of a space allow patients to hear others? Can patients safely walk across a space? Will patients be warm enough?

Lighting comfort. Using ANSI/Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) RP-28-20, Recommended Practice: Lighting and the Visual Environment for Older Adults and the Visually Impaired, when designing patient and staff areas can help designers address issues experienced by the aging demographic using outpatient and hospital facilities.

Coupled with requirements in ANSI/IES RP-29-22, Recommended Practice: Lighting Hospital and Healthcare Facilities, a design can be completed that meets the specific functions (e.g., procedures, examinations and operations) provided in an outpatient facility or hospital as well as the needs of the demographic being served.

A primary contributor to lighting comfort, reduction of glare with daylight controls provides daylight and views of nature as cited in the environment of care section of the Guidelines, while also allowing patients to choose desired light levels. Evenly lighted flooring and ample lighting on other surfaces for the task at hand can reduce fall risk, increase safety, decrease errors and increase comfort.

Contrast used appropriately can benefit patients. For example, light reflectance values (LRVs) that create a higher contrast between floors and walls, grab bars and walls, and handrails and walls can all provide visual cues that help patients identify and use products that can decrease fall risk (e.g., grab bars). Conversely, inappropriate contrast on a flooring surface may cause the illusion of a change in height or create vertigo, increasing the potential risk of falls. Further, lighting of thresholds supports ambulation, particularly if there is a flooring surface change (of color and/or material) between adjacent spaces.

Lighting comfort can also be increased by using constantly improving LED technologies that make it possible to use circadian lighting systems that improve outcomes for staff and patients. Several manufacturers can assist the interior designer, architect, lighting designer and electrical engineer with circadian lighting design, including ways to meet guidelines and code-required light levels. For more information on lighting and health, facilities professionals can access recommendations from the Mount Sinai Light and Health Research Center at the Icahn School of Medicine, which is directed by Mariana Figueiro, Ph.D., professor for population health science and policy.

Additionally, the National Institute of Building Sciences created the Design Guidelines for the Visual Environment, a resource that includes LRVs that are used for various types of surfaces and planes to create appropriate contrast levels in the built environment. LRV is measured on a scale ranging from zero (absolute black) to 100 (pure white).

Some interior products manufacturers, particularly those of paint and flooring, include the LRV on their samples or in the sample binders.

Acoustic comfort. All hard surfaces must be balanced with the need to address acoustics within a space. For example, in outpatient exam rooms, the space needs to be absorptive enough for a patient to hear the information being explained by the doctor or physician’s assistant. In an orthopedic rehabilitation setting, if an older adult’s glasses and hearing aids are removed before surgery and not returned after surgery and they are on pain medications, it will be difficult to see and hear instructions being provided by the rehab physical therapist. Not only do staff need to patiently explain and write down information for older adult patients, but the spaces must be acoustically conditioned to allow older patients to comprehend what they are being told.

From an infection control perspective, the ceiling and higher wall panels are two locations typically recommended to accommodate methods for reducing noise and absorbing sound. Some resilient flooring also has acoustic properties that may assist with dampening noise. In settings used by older adults, where patient health and wellness are central, patient comfort and safety are primary drivers for choosing materials that support both acoustics and cleaning and disinfection. As well, furnishings, room shape and window treatments can all positively affect absorption of sound and reduction of noise.

Part of the functional programming process should be to identify the level of acoustics needed in each space type and to consider where acoustic solutions such as sound-masking equipment may provide the privacy needed for confidential conversations between patients, family and clinicians. The Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospitals also includes guidance on design of medication areas to reduce errors. Both appropriately designed acoustics and lighting are paramount to reducing the potential of medication errors.

Mobility comfort. Mobility devices are used extensively in outpatient and hospital settings and may include canes, wheelchairs, walkers and scooters. Patient spaces, as well as the pathways used by older family members visiting patients, need to be evaluated and considered when designing health care facilities. Functional programming and the completion of the safety risk assessment offer opportunities for the design team to request information from the care provider. Information on the number and location of falls, age of patients and number of visitors can all be valuable context for designing with a focus on any problem areas that could reduce potential fall risk.

Wayfinding can be challenging in hospitals and having safe places to pause, where an older adult can rest for a moment, encourages ambulation. Provision of appropriate seat heights, seating with arms and seating that is not too deep all reduce potential fall risk while serving as a means for older adults to navigate longer distances as required. Designers should note that touch points need to be designed with cleaning and disinfection in mind; therefore, solid-surface materials, metal and other durable arm surfaces are recommended. From an LRV perspective, a contrast between the seat and the floor provides a distinct edge that can be identified when someone who may have mobility and visual challenges sits down.

For grab bars, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was originally based on a veteran population returning from Vietnam that included predominantly male paraplegics with upper body strength. For this reason, ADA guidelines, albeit very important, often do not adequately address the needs of older adults. In the Guidelines, an alternative grab bar configurations table is provided to help designers meet older adults’ needs in toilet rooms. These configurations are based on a research study in the April 2018 Health Environments Research & Design Journal titled, “Beyond ADA Accessibility Requirements: Meeting Seniors’ Needs for Toilet Transfers,” that provided heights and positioning of grab bars that would be more appropriate for older adults.

All accessibility codes need to be met based on the jurisdiction, but it is recommended that alternative grab bar configurations be used where appropriate. This may also include a conversation with the building department and the licensing code regulators as a means for alternatively meeting the intent of the ADA and the International Code Council’s ICC A117.1, Accessible and Usable Buildings and Facilities, based on the demographic of the specific population being served.

Inclusion of handrails on both sides of corridors is typical in hospitals but often not considered for outpatient settings. Handrails that are not blocked by equipment or carts provide a means for safer ambulation from location to location in all types of health care settings serving older adults.

Another consideration when designing spaces is to identify where a specific device is to be stored once a patient or family member arrives at their appointment, procedure or visitation. Storage or “parking areas” may be needed to reduce clutter, provide room for cart and bed traffic, and reduce potential fall risk.

Thermal comfort. Thermal comfort is both physical (e.g., temperature, airflow and humidity level) and the perception of warmth in a space.

Typically, health care staff requires a cooler temperature when working, whereas patients and particularly older adults are often more comfortable in warmer spaces. Some ways to address the physical temperature include use of targeted radiant panels in patient areas that do not impact the staff as much as central or entire room heating systems.

For bathing and shower areas, use of radiant floor heat can add comfort for the patient, while not affecting the health care staff as much as overhead heating devices or lamps. Depending on the procedure being completed, appropriate storage for heated blankets can be provided in health care settings to address the thermal comfort of patients.

The perception of warmth can also be achieved by using warmer colors, warmer light temperatures (at the appropriate time of day based on circadian lighting systems), accent lighting, artwork, and — where appropriate — fireplaces (typically electric) that create the atmosphere of a hearth room.

Improved outcomes

Focusing during the design process on both the demographic profile and the diagnoses of patients who will use a facility provides opportunities to create a built environment that can foster safe and healthy interaction.

Instead of creating an impediment to older adult use, the environment can support and advance as much independence as possible through the functional programming process, which includes addressing the environment of care and the safety risk assessment and attending to details that support inclusivity for people of all age demographics and abilities who will use the health care space.

All design professionals can improve patient and staff outcomes through the design of the built environment. A successful project delivery process results from the collaboration of an interdisciplinary team that maintains consistency throughout functional programming, design, construction, occupancy and post-occupancy evaluation. This team comprises representatives of all community stakeholders who will use a finished building.

The team should aim to achieve inclusivity for all demographics served and to identify and address staff needs. The development of an overlay that evaluates points of human interaction and activities that occur in all spaces, including where services are accessed, can help designers reach these goals.

Jane M. Rohde, AIA, FIIDA, ASID, ACHA, CHID, LEED AP BD+C, GGA-EB, GGF, is principal of JSR Associates Inc. and founder of Live Together Inc. She received the Pioneer Award from the Facility Guidelines Institute for her work on the development and ongoing cycle updates of the Guidelines for Design and Construction of Residential Health, Care, and Support Facilities. Rohde can be reached at jane@jsrassociates.net.