Three steps to becoming a more sustainable facility

Optimizing operations is the first critical step hospitals can take to become more sustainable.

Image by Getty Images

The concepts of environmental sustainability and decarbonization have gained momentum over the last few years. Hospitals and health care systems are being called to become more sustainable through several initiatives.

These include the White House and Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Climate Change and Health Equity Health Sector Climate Pledge, under which, as of April 2024, 139 health care organizations representing 943 hospitals have made the voluntary commitment to reduce emissions, as well as the Inflation Reduction Act, which offers financial incentives to address deferred maintenance of assets.

Three critical steps allow hospitals to take action to become more sustainable.

Image courtesy of the American Society for Health Care Engineering

However, many organizations are still asking, “How do we get started?” Three critical stages allow hospitals to take action to become more sustainable. They begin with optimization and reducing the reliance on greenhouse gases (GHGs). Second, facilities must increase clean power options and electrify their thermal loads. The third stage is reducing carbon emissions through the value chain, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and fully decarbonizing (see the graphic above).

Facility optimization

This article focuses on the first stage of action, which centers on facility optimization through energy efficiency, water efficiency and waste reduction:

Energy efficiency. As pillars of the community, hospitals provide care for patients and support to those in need. Patient health and wellness are key to the mission of health care organizations. However, the health care field is responsible for 8.5% of U.S. GHG emissions, and the rise of GHG emissions is contributing to climate events across the globe. These climate events influence communities and patients, which increases the need for hospital care. This, in turn, increases GHG emissions. It’s a circular effect, and the circle needs to be broken.

Breaking the circle starts with optimizing the facility, and energy management plays a critical role in this. Hospital buildings have high-energy demands that lead to environmental and operational cost impacts. Optimizing hospital buildings through energy measures helps to mitigate challenges and enhance patient care and organizational sustainability.

Key strategies for energy efficiency in hospitals begin with implementing modern building technologies and design principles. Efficient lighting systems; heating, ventilating and air-conditioning systems; and renewable energy sources help to reduce energy consumption and, in turn, carbon emissions.

Additionally, smart building technologies allow facilities professionals to monitor and control energy usage. Systems such as fault-detection diagnostics provide data analytics for users to manage energy use, proactively monitor building system issues and identify optimization strategies for continuous improvement.

Beyond infrastructure upgrades, the promotion of energy-conscious behavior is key for optimizing energy use. Encouraging simple actions, such as turning off lights and equipment when not in use, is beneficial for reducing energy consumption and costs. The American Society for Health Care Engineering’s (ASHE’s) HealQuest™ program was developed to help hospitals educate staff and modify behavior on energy efficiency opportunities and other optimization techniques.

Collectively, investing in energy efficiency through infrastructure and staff education provides a holistic approach to optimizing energy use.

Water efficiency. A defining factor of sustainability is that the proposed solutions must last a long time yet do no harm. As it pertains to water in plumbing and mechanical systems, this remains at the forefront of the conversation. Will this modality or guidance age well? Will this material hold its integrity and value? Will the implementation be safe to all who use the water? These are questions that sustainable engineers, contractors and operators ask themselves all the time.

The digital age of water has funneled in many innovative solutions to age-old challenges, including the fight against waterborne pathogens, such as Legionella. The integration of digital tools with expert training and good data collection can transform a water management program. This approach not only enhances water safety but also streamlines the management process, making it more efficient and effective.

When designing sustainable water management solutions, facilities professionals start with three sequential fundamentals for building any program or protocol — organize, optimize and scale — while utilizing feedback to further increase precision. Building a water management program should be no more difficult than placing the appropriate efforts in that sequence to help any team get started.

Organizing is the most important part, and defining the parameters for data collection gives the optimization phase the valuable information it needs to make the best decisions from a fully detailed history. Understanding how much water a building consumes, where it’s consumed and by what components it generates or purveys function can provide insight that is often overlooked. Historical data allows for better optimization, or perhaps simulation, to get ahead of future issues. Starting the collection of water parameters early and often during construction and any disruption is how mitigation tactics can be deployed and design functionality can be preserved.

Water management requires continuous education on emerging topics and modern plumbing components. The presence of Legionella or other waterborne pathogens poses a significant risk to patients, staff and visitors. There is a critical need for specialized training in this area, and the utilization of skilled tradespeople or trained plumbing professionals can make all the difference.

ASHE provides educational offerings specific to health care water management program development. This provides guidance on developing a working water management program or improving a current program. Additionally, ASHE has published a monograph on “Water Management in Health Care Facilities: Complying with ASHRAE Standard 188.” It provides guidance on the development and management of a water management program.

Water management safety plans should emerge on the jobsite prior to construction or disruption in conjunction with the designated water management team. This allows the team to control valuable and informative water baseline data.

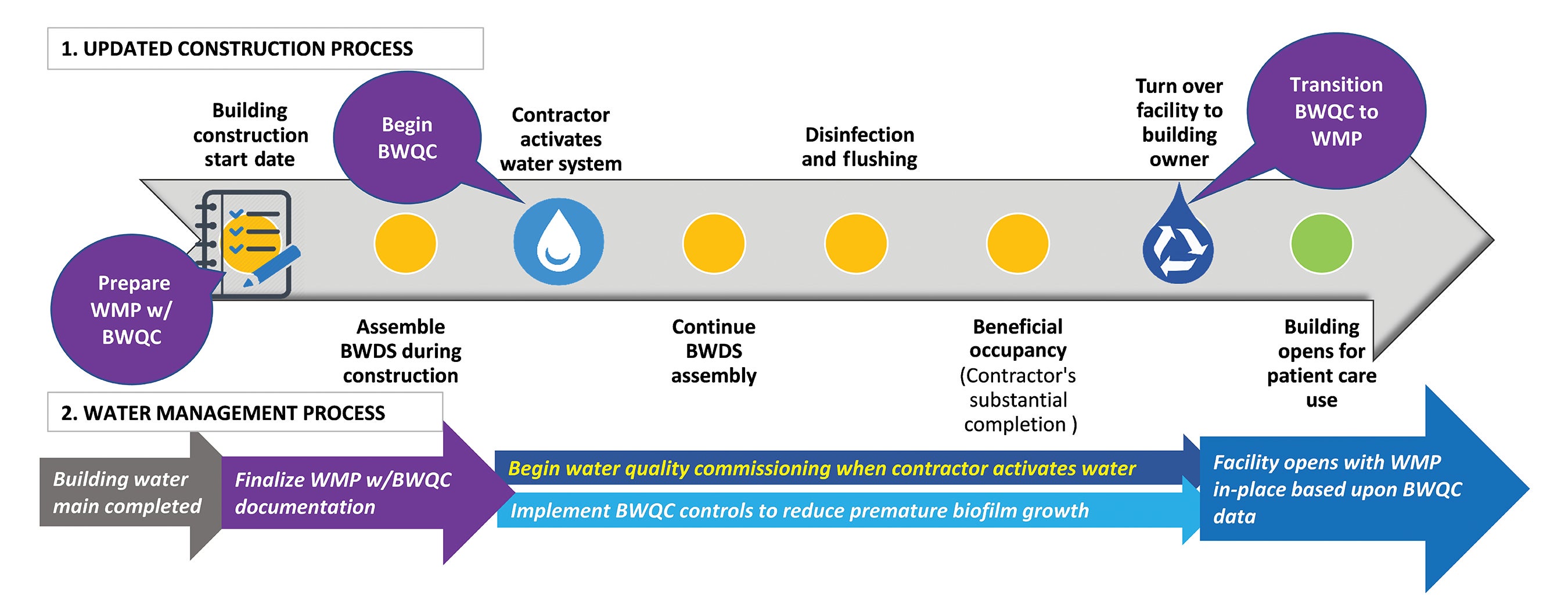

As Scanlon et al. recommends in the Buildings article “Building Water Quality Commissioning in Healthcare Settings: Reducing Legionella and Water Contaminants Utilizing a Construction Scheduling Method,” every health care construction project should develop a water management construction schedule (see the graphic below). When the project schedule is developed and data is collected, such as startup water dates, flushing records and the operating procedures based on design, organizations can lower risk and provide a safe and healthy physical environment for all occupants, especially for sensitive patient care units.

The history of a plumbing system’s usage or nonusage data is critical in the organization phase of building a good program. When a water-based system collects good data, optimization can become simpler. The results of measuring or documenting a water system’s function could easily lead to future opportunities for water conservation and other potential decarbonization solutions.

Building occupancy and probability of use play key roles in those potential reduction opportunities. Tracking trends or changes in a water management plan can provide awareness. If the results don’t lead to a reduction of water use, it could lead to other opportunities, such as water energy storage, detention and reuse, when all things are considered.

It’s crucial for facilities professionals to foster a culture of continuous education among plumbing and water management professionals and all members of a sustainability team. Encouraging them to engage with standards development, with ongoing education and certification renewal, is how facilities ensure their systems last a long time and do no harm.

Prioritizing these tactics for a sustainable health care environment can ensure that water management practices not only comply with current standards or codes but also continuously set new benchmarks for safety and efficiency.

The International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO) offers an ASSE/IAPMO/ANSI 12000, Professional Qualifications Standard for Water Management and Infection Control Risk Assessment for Building Systems, series for plumbers and water management professionals aimed at infection prevention and water quality, as well as a new IAPMO publication titled “Construction Practices for Potable Water.”

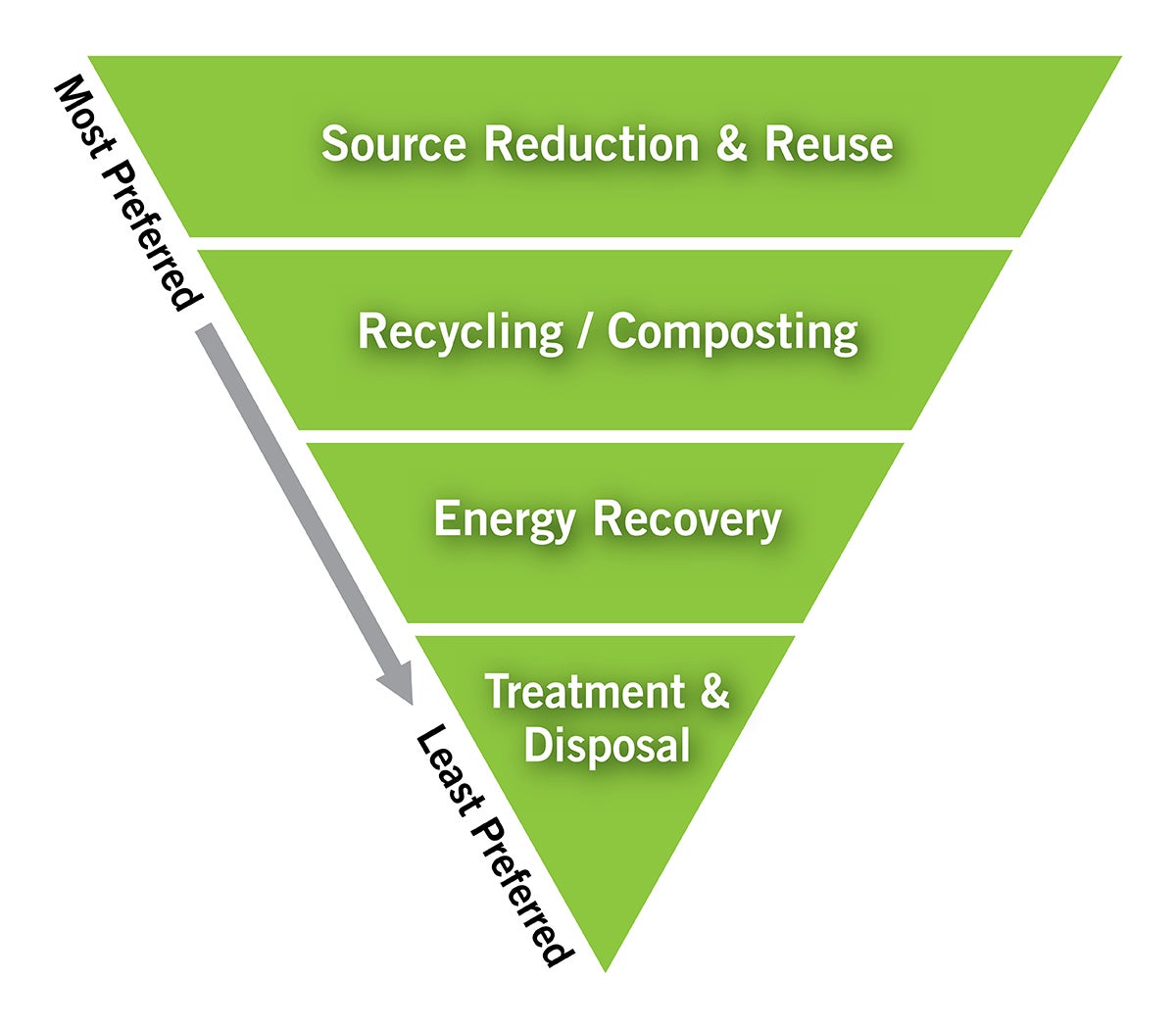

Waste reduction. Health care can be wasteful as the field has moved over time to prioritizing single-use supplies. However, with hospitals looking at sustainability and supply chain resiliency in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the field is ripe with opportunities to reduce waste, avoid landfills and look to a circular economy. When approaching waste reduction, the Environmental Protection Agency’s waste management hierarchy (see graphic at right) is generally seen as best practice for non-hazardous materials alongside the reduce-reuse-recycle mantra.

For health care, this can be translated into opportunities to expand recycling efforts, whether targeting hard-to-recycle plastics, assessing materials that can be used more than once or simply preventing waste from entering the facilities from the start of any contractual agreements.

Although waste has a relatively low Scope 3 GHG emissions factor compared to health care’s other emissions, it has a large physical and social impact — with waste often seen as a visual indicator of a hospital’s commitment to sustainability.

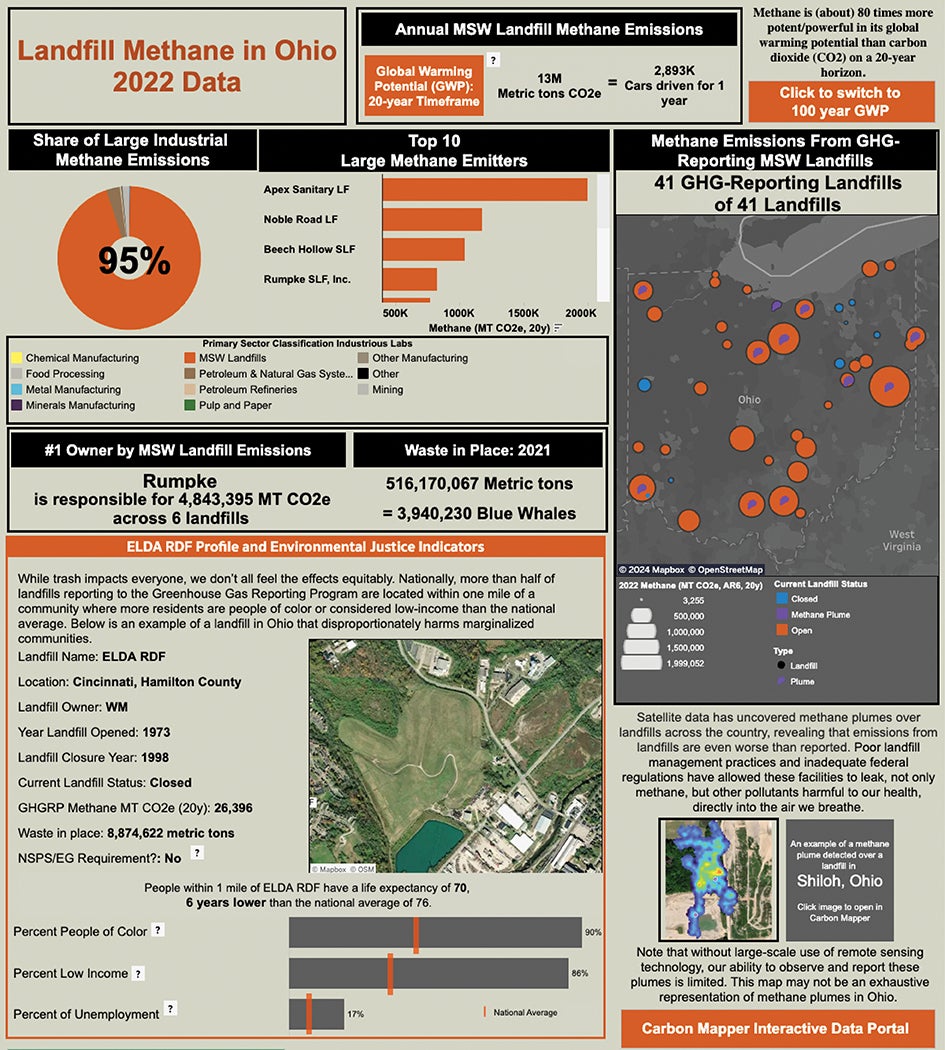

It’s also important to remember human health and environmental justice impacts of waste disposal on people and communities, with low-income and communities of color often living near landfills and incineration plants. With climate change already disproportionately impacting people across the globe, the link between landfill locations and poor and minority areas is a vital environmental justice issue to keep in mind when addressing waste (see the graphic below).

Circular economy can be practiced by taking a facility’s compost and using it to replace synthetic fertilizers used on the hospital grounds or shared with local community gardens.

Image courtesy of OhioHealth

After providing recycling infrastructure for public-facing and employee-facing areas, expanding to the operating rooms (ORs) is an impactful next step. Nearly 30% of waste comes from ORs in U.S. hospitals, and much of that includes hard-to-recycle plastics. If existing waste-hauling partners do not accept items from the OR, additional partners must be found to accept the hard-to-recycle items, such as sterilization wraps, anesthetic gas canisters, irrigation bottles and general plastic bags, among others.

Given the risk of contamination in waste streams leaving ORs, transparent bags are recommended, with unique identifiers that are different from those used for other hazardous waste streams. Consolidating the recycling from the ORs in a single location that can be accessed by the environmental services department and taken to the dock on a regular basis will help meet time constraints for staff. Medical device reprocessing is another great landfill diversion tactic coming out of ORs, as it not only comes with a positive financial impact but also supports an overall more resilient supply chain.

Finally, understanding the recycling process itself is important when weighing the overall environmental impact of a product’s end of life, as recycling processes across the country look different as do their impacts on public health.

Following a circular economy approach can also support a more resilient supply chain, as many hospitals around the country lacked sufficient personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Switching from single-use, plastic isolation gowns to washable gowns that can be washed over 40 times per gown not only reduces plastic, avoids landfills and reduces operational costs but also provides facilities with more reliable and localized supplies. As cost differences are compared, the key is to understand a product’s cost per use or its life-cycle cost.

For example, although washable gowns may appear to be more expensive due to upfront cost, washing the gown over its life will provide a lower cost per use than a single-use, plastic gown alternative. The same can be accomplished by assessing medical device contracts for reprocessing opportunities, using rechargeable batteries and so on. With supplies that eventually end up in hazardous waste streams, it is also important to include disposal costs in the overall cost of a product.

Like ORs and medical supplies, hospital kitchens face waste dilemmas as they maintain specialized, nonstop food services that require large menus for health-based diets. Scaling back items on menus and monitoring wasted items prevent food waste before it enters the kitchens, allowing the focus to shift to food scraps and uneaten food from patient trays.

With space and operations often dictating food waste disposal possibilities, assessing landfill alternatives such as third-party composting, digesters and animal feed is a last resort after establishing food donation partners. A circular economy can be practiced by taking a facility’s compost and using it to replace fertilizers used on the hospital grounds or shared with local community gardens.

Energy conservation measures

Organizations are being tasked with decarbonizing and electrifying their infrastructure. In addition to regulatory challenges and securing capital funding and staff, figuring out how to begin is perhaps the biggest hurdle.

Identifying projects and initiatives that require minimal resources to implement is a great place for an organization to start to build momentum and realize savings. The American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) has developed over 50 strategies and energy conservation measures that highlight how to get started and maintain progress toward sustainability implementation in a health care organization.

Separated into eight categories — prepare; schedule; control; repair; audit; replace; planning, design and construction; and general sustainability — these energy conservation measures (ECMs) range from high-level organizational strategies like developing an environmental principles statement and key performance indicators to operational procedures like practicing preventive maintenance, peak shaving and load shifting, and airflow setbacks.

Every health care facility has unique capabilities and nuances. Some may already be utilizing practices like these while others may just be beginning to address them.

These ECMs can be leveraged to optimize health care facilities and energy management procedures to reduce consumption, increase efficiency and realize savings. A benefit to quick return on investments is that it allows those savings to be reallocated toward priorities like patient care and facility improvements. Additionally, providing realized savings to hospital leadership aids in the justification of future sustainability and decarbonization projects that might require more capital to implement.

Whether an organization has been implementing sustainability and decarbonization projects for some time or is just now getting the ball rolling, ASHE’s ECMs provide a useful tool to help guide them along the path toward sustainability.

John A. Mullen is an ASSE 12080 Certified Legionella Water Safety and Management Specialist and director of technical services and research at IAPMO; Allegra Wiesler is sustainability advisor at OhioHealth, Columbus, Ohio; Kara Brooks is senior associate director of sustainability at ASHE; and Austin Wallace, MA, is sustainability senior specialist at ASHE. They can be reached at john.mullen@iapmo.org, allegra.wiesler@ohiohealth.com, kbrooks@aha.org and awallace@aha.org.