Room to heal

Health care design is growing more sensitive to the needs of patients, nurses, doctors and staff in various specialties. Today's hospitals must suit everyone's needs; each department tends to have its own requirements for space design, furnishings and equipment. This creates a comfortable environment both for healing and for working.

Health care design is growing more sensitive to the needs of patients, nurses, doctors and staff in various specialties. Today's hospitals must suit everyone's needs; each department tends to have its own requirements for space design, furnishings and equipment. This creates a comfortable environment both for healing and for working.

Orthopedic departments, for instance, have special requirements for patient rooms as well as the waiting areas, rehabilitation and inpatient and outpatient physical therapy units. The corridors through which orthopedic patients travel to and from waiting areas and finally to a patient room or treatment space, need special design considerations as well.

While the following concepts and products focus primarily on orthopedic and rehabilitation facilities, they also offer considerations for general health care settings which must accommodate nonorthopedic patients who have a variety of mobility issues.

Comfort in the waiting room

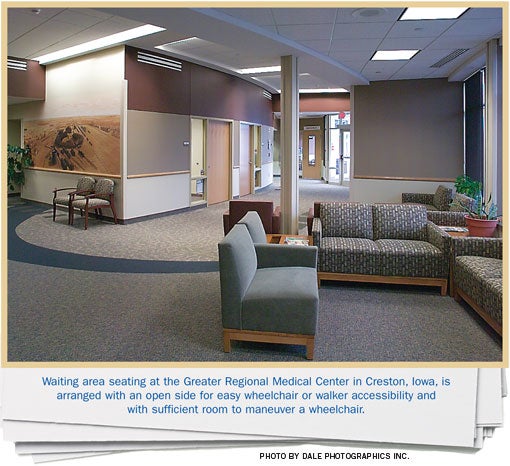

Waiting rooms must accommodate people with mobility problems as well as illnesses and injuries that don't affect mobility. While some of the following considerations may apply to any department waiting area, they mostly consider the needs of patients using walkers, crutches and wheelchairs in rehabilitation, physical therapy and orthopedic waiting areas.

In these areas, patients need space to stow crutches and walkers and to park wheelchairs. That means the seating arrangement in a waiting room must allow sufficient space between some of the chairs for this equipment.

Wheelchairs are 20 to 24 inches wide, so their parking spaces should be wider than 24 inches. Patients in wheelchairs sometimes must elevate their feet and legs to control swelling and pain by extending the leg and foot supports horizontally to between 2 1/2 and 3 feet in front of the chair. The waiting room's circulation paths must accommodate that by allowing for 6 to 8 feet in front of the wheelchair.

People with mobility problems need special furniture. The Outlook Linden from Nurture by Steelcase (www.nurture.com), Grand Rapids, Mich., features large, sturdy arms, which extend all the way to the front of the chair and open space under the seat to get feet as far back under the body as possible. This allows a patient to push up to a standing position and transition to a walker or crutches.

However, this design won't suit every patient. The Nurture line also offers a chair without arms, which enables a patient in a wheelchair with a lift arm to slide into and out of the chair. This option is especially useful in waiting areas with limited space.

Chairs like the ones found in the Nurture line also support the role of comfort in healing. For instance, in an emergency room, family members might want to move chairs together to create a more intimate and secure group seating arrangement.

Bump-free traveling

Getting in and out of the waiting room can challenge orthopedic patients as well. This is usually due to flooring choices that make movement difficult or obstructive thresholds across main entrances and exits. At the same time, flooring materials must offer durability and easy maintenance while avoiding emissions that adversely affect indoor air quality.

InterfaceFlor LLC (www.interfaceflor.com), LaGrange, Ga., makes an excellent carpet for waiting rooms as well as corridors. It offers hospital-grade durability and solution-dyed colors for easy cleaning. Although more expensive than broadloom, the carpet tiles make it possible to replace small sections that suffer damage or staining rather than the entire carpet. In the case of a stain, it is possible to replace a tile or two from extra stock, and have them professionally cleaned and inventoried to handle future spills. The pile of the material is dense enough that moving equipment with wheels, wheelchairs and walkers is similar to moving it on a hard-surface floor.

Heavily textured porcelain or stone tile should be avoided in orthopedic areas. The rough surfaces and joints can make for painful travel when patients have hypersensitivity in their limbs from an injury or surgery. They also can be a tripping hazard for patients using walkers or crutches. Many new patients do not have the strength to lift their walkers and must slide them along the floor.

Thresholds don't need to be perfectly smooth; they should, however, be free of the typical threshold bump that can snag walkers and wheelchairs. Johnsonite (www.johnsonite.com), Chagrin Falls, Ohio, and others make thresholds to transition between carpet and hard-surface flooring. These transitions feature exposed surfaces with links for stretch-in or adhered carpet and taper down to almost flush.

For the thresholds between the patient corridor and room, Johnsonite has transitional thresholds that can allow for a "bumpless" move from carpeted corridors into rooms with sheet-vinyl floors.

Corridor considerations

Primary design considerations in corridors include flooring, equipment alcoves and lighting. Secondary considerations include colors and textures.

Generally speaking, the same flooring materials suggested for waiting rooms work well in corridors, with one proviso: acoustics. A problem associated with hard flooring surfaces in corridors is noise and there is a growing trend toward carpeted corridor floors to absorb noise.

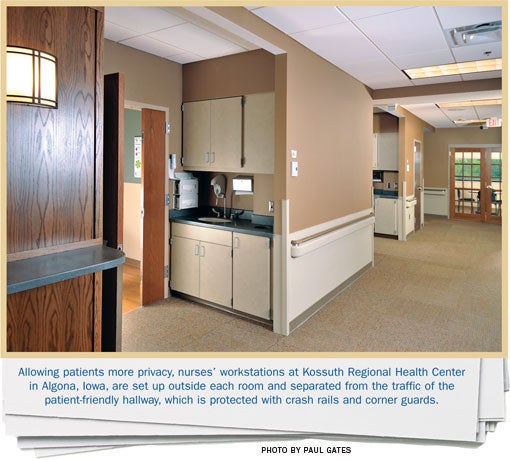

In health care occupancies, corridors must allow at least 8 feet of width. Equipment alcoves for temporary storage of patient beds or other equipment are typically 3 feet deep and 8 feet long. About midway down inpatient corridors, more permanent storage for larger equipment could be provided in rooms of about 150 square feet.

What activities do these dimensions accommodate? Nurses and staff constantly move beds and gurneys in and out of rooms and through the corridors, while the dietary and housekeeping staff push fleets of carts through the halls — all navigating corners. Flush-mounted corner guards protect the corners from damage when the beds and carts bang into them.

Construction Specialties Inc. (www.c-sgroup.com), Muncy, Pa., has wall guards with cushioned bumpers that can be replaced easily when damaged. Its Acrovyn line includes corner guards, crash rails, handrails, and door and frame protectors as well as wall-protection boards.

Lighting, the second important consideration, is trending toward indirect fixtures set into coves along corridor walls. This is more soothing than overhead fluorescent lighting in traditional 2-by-4-foot fixtures positioned along the ceiling's centerline. Overhead light can be harsh on patients' senses as they lie on their backs while being transported down the corridors.

Color and texture also add to the sense of hospitality. In that regard, earth tones and light and dark woods help play down the institutional feeling. Textural accents might include recessed doors, light sconces, wood accent panels and framed photos.

Orthopedic-friendly rooms

There is no brand name for the single, most important commodity in a patient's room. It's space, and lots of it. Budgets always create pressure to cut costs, and space usually makes an attractive target. The bed, lights, furnishings and bathroom must all be in the patient room. But rooms that start with sufficient space, often end up crowded due to budget cuts along the way.

One trend that does not seem beholden to budgets: the private rather than the semiprivate room. Semiprivate rooms are not being built in new facilities while older facilities are converting existing semiprivate rooms to private. A major benefit of private rooms is more space for patients, families and furnishings, and thus a higher quality of care and more comfortable healing environment.

Planning an ideal room makes it possible to think about adequate space and a full complement of furnishings. Such a room provides space for a patient, bed, chair, bathroom, family zone, and such furnishings and equipment as a television, closet and a lifting device for patients who need assistance getting out of bed.

In thinking about the optimal size of an orthopedic patient's room, the first consideration is the patient zone size. Typically, hospital beds are 3 feet wide and up to 7 1/2 feet long. As a rule of thumb, there should be about 5 feet of clearance on both sides of the bed to allow plenty of working room for equipment, physicians and nurses, as well as space for family and friends to gather around. In addition, many codes require 4 feet of space beyond the foot-end of the bed. Five feet is a better number. So an ideally-sized patient zone is about 13 feet by 12 feet.

In addition to the patient zone, an ideal room includes a family zone against the wall farthest from the door and a nurse work zone just inside the door. By placing the bathroom along the outside wall, a designer can make room for large beds and gurneys to wheel easily in and out of the room. The closet, meanwhile, might be placed next to the bath. Together, all these spaces call for a room size range of approximately 13 feet, 10 inches wide by 18 feet, 6 inches deep (excluding the bathroom). This is reasonable size for needed clearances.

Bathroom requirements

Orthopedic patients require different bathroom designs from those suitable for most patients. Patients in wheelchairs or using walkers need extra room to maneuver. And that's only if they can get into the bathroom on their own. If they can't, it often takes multiple nurses to help them use the facilities.

Most bathrooms don't allow enough room for this much-needed assistance. Many bathroom doors open toward the room's entry door or open into the nearby privacy curtain, often creating a distraction when staff must help a patient get in there in time.

Design considerations should include a door wide enough to accommodate a wheelchair. Some patients will need a wider room than the Americans with Disabilities Act requirement because their wheelchair configurations cannot be accommodated in the common 5-foot turning radius.

Some hospital bathrooms now are being designed entirely as a shower. Such a design requires a raised threshold to keep the water in. But thresholds impede the movement of wheelchairs and walkers. An alternative to the threshold is a flush trench drain set right in front of the door. This would not replace the main shower drain but only stop the movement of water out of the bathroom.

GrifForm Innovations (www.grifform.com), Roseburg, Ore., is a company that fabricates DuPont's Corian material into a Bath Pod. This is an ideal solution for a total shower bathroom. It has an impervious floor that can be fabricated off-site with integral trench and shower drains. The innovative design allows the door to glide open and closed, so no more bathroom door banging into the room's entry door. It has ample room and a low threshold entrance.

For more conventional bathrooms on a tighter budget, a seamless nonslip flooring from Armstrong World Industries Inc. (www.armstrong.com), Lancaster, Pa., called Safeguard Spa, or similar products from Johnsonite also can work. In this situation an independent trench drain and main drain would have to be installed in a more conventional fashion.

Of course, grab bars must complement different functions of the bathroom. These products are stock items — except for the materials. One newer custom design incorporates antimicrobial copper. Though more expensive than conventional grab bars, they have been shown to have antimicrobial properties. This material is to be considered a supplement to standard infection control measures.

Innovative designs

If this look at designs fitted to orthopedic patient needs proves anything, it is the huge range of innovative products and equipment on the market today. There is something for virtually every problem an orthopedic patient may encounter.

Products exist to make recovering easier and more comfortable for patients. But it takes a health care architect with a broad knowledge of available products and a deep understanding of patient needs to develop and integrate effective designs.

Mark Anderson, AIA, is a senior architect for health care services in Shive-Hattery Inc.'s Bloomington, Ill. office. He can be reached at manderson@shive-hattery.com.

| Sidebar - Some furniture suggestions for orthopedic patient rooms |

| Health care facilities long have been prime target markets for designers and manufacturers in the contract furniture industry, but nowhere has their attention grown more intense than in the patient room. Following are a few suggestions to consider when specifying furniture for orthopedic patients. • Patient beds. Orthopedic patients should have beds that can be lowered close to the floor, making it easier with the assistance of a slide board to move between the bed and a wheelchair or a lounge chair. The GoBed II medical-surgical bed from Stryker (www.stryker.com), Kalamazoo, Mich., is one of the few beds on the market with exceptional low height. It also has intuitively adjustable side rails, retractable fifth-wheel mobility and, with one-button touch, it can transform from full recline to an upright cardiac position. • Overbed tables. The often-overlooked overbed table finds itself heavily used and misused by patients, visitors, nurses and doctors. From Nurture by Steelcase (www.nurture.com), Grand Rapids, Mich., the Opus overbed table withstands such use and misuse. For example, one of its chief innovations is the provision of an adjustable patient surface and a stationary stand-up surface for caregivers. The caregiver surface features an integrated, seamless spill-retaining edge, plus additional small extension surfaces that can be pulled out or hidden away. Beneath the surface is a cubbyhole for charts. The lower surface is designed around patients' needs. It has a concave edge, so that it can be brought much closer to the patient than traditional rectangular tables. Its surface, like the tall side, offers a seamless spill-retaining edge, while integrated cup holders help prevent spills. An optional personal drawer with a small vanity mirror can be installed under the patient surface. A particularly innovative feature allows the table to rise by pulling it up — no need to use a lever. This prevents accidents caused when someone raises the bed without checking to see if the table is across the bed. When the bed rises, so does the table surface. • Patient chairs. The importance of a patient chair should not be underestimated. It gives the patient an opportunity to get out of the bed into a different position and, thus a sense of having some control over his or her situation. Brandrud Nala patient chairs, from the Herman Miller Healthcare and Nemschoff subsidiaries of Zeeland, Mich.-based Herman Miller Inc. (www.hermanmiller.com), are well-cushioned and comfortable and mimic natural body motion. The side arms can be removed, enabling the patient to slide between bed and chair more easily. A sacral support keeps the patient's lower back area relaxed and prevents slumping. While a barrier-free foot area aids patients with hip replacements in standing up with steadiness, the freestanding ottoman can be used as a footrest or to support a 350-pound friend or family member. |

| Sidebar - An architect's personal experience with orthopedic design |

| Author Mark Anderson's article is not just the perspective of an experienced architect. It's also the perspective of a husband who encountered dozens of small design flaws throughout his wife's three-month in-patient orthopedic treatment and nearly a year of outpatient use of various mobilizing devices. It became clear that better design could have reduced frustration for all involved, and very likely assisted with the healing process. During her hospital stay and numerous follow up trips to various medical and rehabilitation facilities, the sometimes-frustrating design issues gave Mark the idea to write this article and inspire better orthopedic unit design practices. |