Master planning smart health care facilities

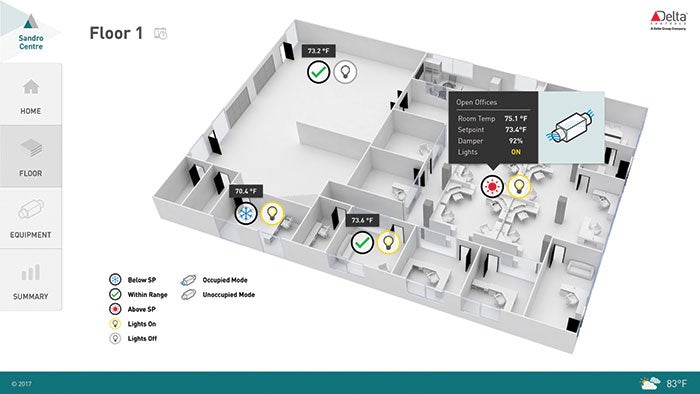

Integrated building automation systems utilizing operating room graphics can give building operators and clinicians insight into the status of the room, and any alarms that could affect the environment of care.

In the era of the Internet of Things and data analytics, building automation systems need a higher level of design and planning, especially in health care.

Hospitals are energy-intensive, 24-hour critical facilities with complex equipment and processes that make improvements difficult and costly both from a construction perspective and because the organization will be losing clinical space.

Add to that the many regulations, ever-tightening reimbursements and large percentages of unpaid care, and hospitals are challenged to find savings in the traditional operation. Operating efficiently is challenging because of the large operational systems running 24/7, and maintaining energy savings and occupant comfort can be inversely proportional.

When a focus is on constraining the already high cost of constructing new hospitals, it often leads to sacrificing the budget for infrastructure through value engineering. However, these are crucial systems that could keep reliability and maintainability high, and great care must be taken to avoid creating high costs over the building’s life cycle for a short-sighted gain in construction.

Non-recurring engineering

The concept of non-recurring engineering is a major driver of decisions that impact production of new products. Simply put, there is great value in designing for production, since the cost of the engineering effort only occurs once and production costs apply to every unit.

Apply that concept to smart buildings. If the owner were to create a standard life-cycle-based system architecture by creating a comprehensive set of requirements for smart building systems, the cost to create that master plan should be offset by reduced design costs spread over multiple projects. A master plan facilitates design packages and facility standards that reduce design resources needed by consulting engineers to redesign systems that already are deployed successfully elsewhere in the health system.

A master plan also helps to minimize scope gaps or unknowns in construction drawing sets that each subcontractor carries as a contingency; markups along the construction tier make even small contingencies add up.

For example, a master plan can create economy in structured cabling for information technology (IT) and building systems. Instead of having a low-voltage subcontractor underneath a mechanical or electrical firm purchase and install low-voltage wiring and terminate network connections, a single low-voltage group can coordinate the cabling associated with the entire project’s scope of work, reducing labor and materials and the coordination required to keep subcontractors in sync.

The reduced cost in coordinating, purchasing and pulling cabling for operational technology (the larger general category for smart building systems) that can now reside all underneath the IT cabling scope of work within a building alone is reason enough to evaluate the cost-saving potential of master planning.

Standardizing smart buildings

Even if it is not possible to take advantage of non-

recurring engineering in the new construction and expansion, hospitals can greatly benefit from standardizing smart building systems inside the same facility or campus.

You may also like

For example, a former federal hospital had two independent HVAC building automation systems — one for the central plant and one for the zone control. This meant that it needed to execute its procurement processes twice for two smaller service agreements, train the facility’s staff on two systems and look at two different consoles to assess building issues or make system changes. These are special cases, but they are typical of what happens as hospitals grow and change.

In these cases, even if extra training and service contract costs can be managed, the result of a loosely specified smart system without much regard to legacy systems effectively stovepipes the infrastructure for future benefits. This makes it difficult for the operators to monitor, control and respond to failures and alarms. Without a common building operations console, the facilities team is inefficient, which is costly and negatively impacts the environment of care.

Standardizing on infrastructure systems simplifies the hospital and provides for greater economy. Additionally, standardizing across the health system gives facilities professionals the ability to more effectively use staff by flexing personnel from one facility to another.

This is already important in multibuilding hospital campuses where facilities must plan their staff to handle the acute care facility, and the outlying outpatient procedure, office and ancillary buildings on the hospital campus; and it will continue to gain importance as more and more health systems build neighborhood facilities with a range of care delivery and the associated regulations for the environment of care.

The more decentralized care becomes to improve clinical operations, the more necessary it becomes to ensure that facilities personnel can remotely monitor conditions and diagnose failures, and then respond with the correct resources and materials to fix any problems.

Planning beyond the bid

Smart building systems are hardware- and software-intensive technologies comprising equipment, control devices and sensors managed with networking infrastructure, processors, computers and servers. Typically, these systems are designed by multiple subcontractors with discrete scopes of work early in the project, based on a loose and generic specification.

HVAC automation bids to the mechanical contractor, while lighting automation, structured cabling and security are subcontractors to the electrical contractor. Fire alarm may be part of the mechanical contractor’s scope or they sometimes bid directly to the general contractor.

In the traditional construction approach, most of the implementation details and technology choices for the smart building infrastructure are pushed down to primarily build-bid-winning packages, which primarily means that price is preferred over design. Working in the lower tiers for multiple primary subcontractors, the hardware and software backbone and brain of the building are designed at the lowest price by a disparate group of contractors that, for the most part, do not collaborate.

However, health care infrastructure is complex and it needs more design and facility systems engineering for sustainability. If the owner cannot commit to a master plan for smart building infrastructure, another method of integrating technology is the use of the Construction Specifications Institute’s (CSI’s) MasterFormat Division 25: Integrated Automation as the coordination point among design, construction and service teams to address technology standardization and integration.

Similar to a master plan for smart buildings, the specification treats smart building systems in a single CSI division, instead of placing parts in HVAC, electrical and other divisions. Consolidating smart buildings to one location drives consolidation and integration in the smart systems and front end, and sets the table to economize the infrastructure cabling and hardware.

A master plan or the use of MasterFormat Division 25 puts the facility professional in a position to not only drive the intelligent infrastructure choices during construction, but also to demand that contractors create a building that is easy to service, takes advantage of emerging technology and ensures a building that operationally fits into the health system at commissioning.

Incorporating medical office and ancillary spaces into the master plan gives a more complete view of the infrastructure, eliminates stovepipes in the campus master plan and increases economies of scale to optimize energy and resource use.

Creating a master plan

A master plan can take many forms. At its simplest, a standard design narrative for smart building systems can be created that ensures consistency with the smart building goals of the health system during construction projects of all kinds.

This design narrative serves as a guide for future engineering and design efforts for new construction or retrofit projects that include HVAC and other building systems capable of being part of a building automation system. It also can take into account building system and infrastructure standardization efforts underway, and help to provide integrated smart buildings at building commissioning.

This smallest of the available master plan documents is basically a consulting effort to align the goals of the health system through a discovery process that interviews stakeholders from IT, operations and maintenance (O&M) leadership, the construction group and, ideally, health care quality personnel to uncover the needs of the organization’s infrastructure.

The design narrative provides contractors, engineers and infrastructure service providers with the following:

- Guidance for preparing engineering specification Division 25 or 23 for new construction and expansions;

- Excerpts of specification language for established smart building standards (e.g., enterprise automation or analytics platforms);

- Guidance for retrofit projects;

- Guidance for projects on sites that have existing, modern building automation systems.

At the other end of the spectrum, a master plan could be a comprehensive Division 25 specification that clearly outlines the smart building requirements at a granular level. Options in the middle are limitless.

The important thing to consider is what the organization wants from the infrastructure and what level of variability is acceptable to meet the needs of the facilities team and the clinicians so they can deliver the best patient outcomes at the highest value.

Developing the plan

Nearly all building automation manufacturers have specification-writing tools that will pop out an “open” specification to add to a facility’s plans. Although some free specifications are better than others, they usually will guide the specification to the creator’s products. This can lock the facility into using a particular provider. A specification that is not biased toward a particular manufacturer provides flexibility in options, and defines components that more closely align to the goals of the health system.

If a facility professional is exploring a building automation master plan for his or her health system, it is likely one of the first systemwide efforts would be to align the O&M groups with the construction teams, so it is best to take a phased approach.

There are a lot of stakeholders to align and not all of them will have the same opinion on the way ahead. Additionally, the buying criteria and current practices are different for building constructors and building operators, and the master plan will constrain both in different ways. This is a major alignment, and change is difficult, so be flexible and open to new approaches.

As internal stakeholders are aligned, facility professionals should attempt to come to consensus on a high-level vision of the desired end state. Maintaining flexibility for the construction professionals and maximizing interoperability and common interfaces for the O&M professionals is possible. This is the time to explore ideas, and fill in knowledge gaps with education from providers, industry media and conferences.

Once a basic understanding is established about what may work for the system, facility professionals should find a master planning partner that is tech-savvy and knowledgeable on the emerging trends in the market. A good partner wants to understand the health system as well as its growth plans, procurement guidelines and IT governance to include cybersecurity before expressing an opinion on the right equipment.

After a partner is chosen, a phased approach should be used to create the level of specification that makes sense for the organization.

Additionally, facility professionals should make a commitment to standardizing. There likely are projects in development that could seed the new master plan and provide a proving ground for the new system standard. The partner can be used to write design guidance to make those projects compatible with the health system’s vision.

Unlocking value

Today’s health care environment is challenging but investing time, effort and money in planning the infrastructure is an easy way to unlock value in the organization.

The challenges of working in the built environment not only are costlier to retrofit or change infrastructure systems after the facility is in operation, but every disruption to clinical services negatively affects operations.

Vincent DelPidio is account executive for Southland Energy, a division of Southland Industries, and Brandon McCarron is system integration engineer for Envise, a subsidiary of Southland Industries. They can be reached at VDelPidio@southlandind.com and BMcCarron@enviseco.com, respectively.