2019 Hospital Construction Survey

Image from Shutterstock

Code compliance is a requirement in health care construction that everyone understands and appreciates. After all, the codes are key to ensuring safe health care occupancies. But code compliance also can be highly frustrating and costly, as most people involved in health care facilities management can attest.

“The amount of money spent on compliance would take a ton of financial resources to make up,” says Chad Beebe, CHFM, FASHE, the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s (ASHE’s) deputy executive director for advocacy.

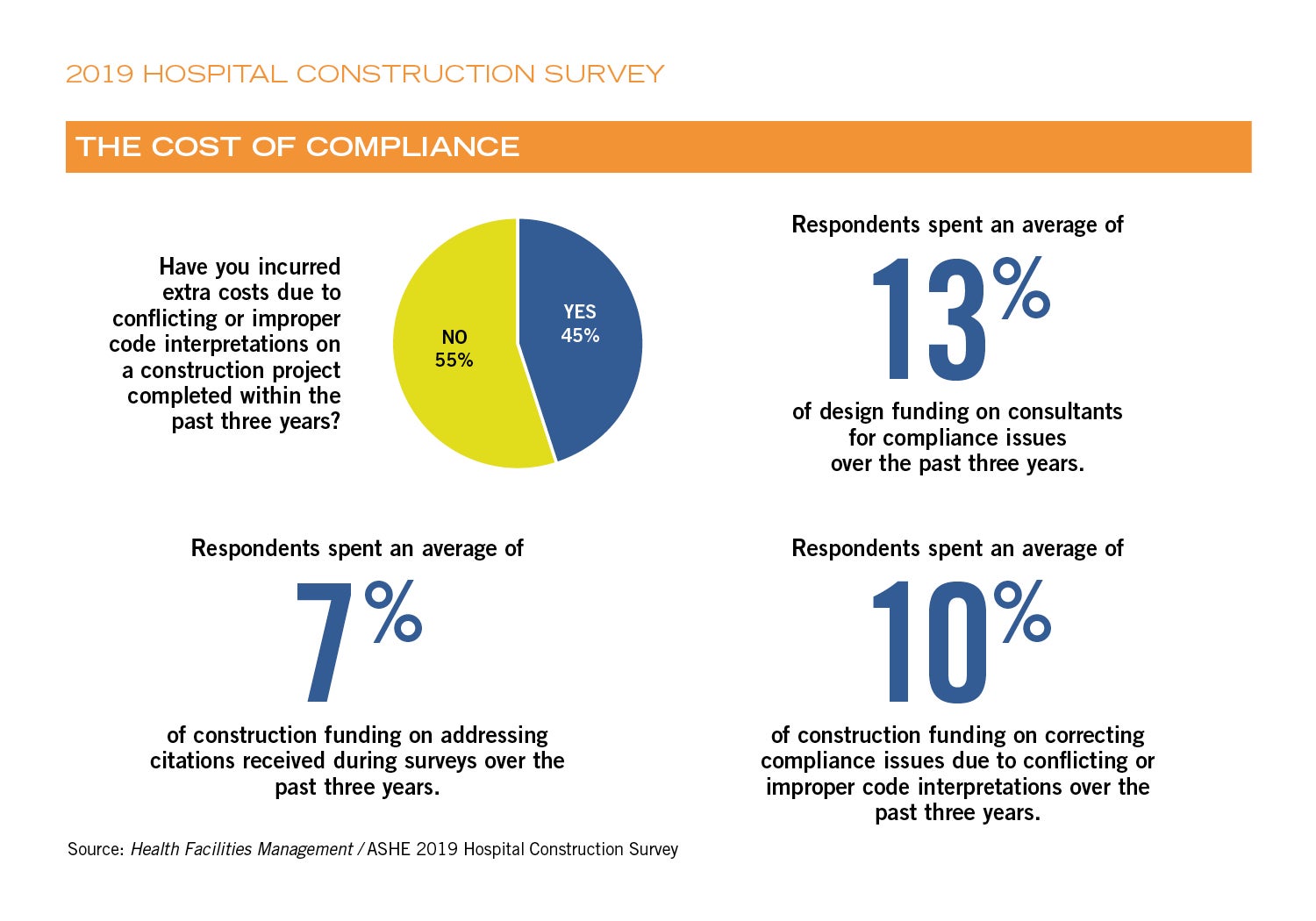

How much does compliance cost? Correcting compliance issues that were caused by conflicting or improper code interpretations costs 10 percent of a hospital’s construction spending, on average, according to the 2019 ASHE Hospital Construction Survey conducted by ASHE’s Health Facilities Management magazine. Questions about compliance issues were asked for the first time in this year’s survey, which also asked a breadth of questions about construction projects and budgets.

“The importance of compliance is protecting lives,” notes Jonathan Flannery, FASHE, senior associate director of advocacy for ASHE. “Keeping patient and staff safety foremost in mind, we don’t want to do things just to save money. But we want to do things in a way that uses resources wisely.”

Conflicting codes

Another question regarding compliance that was asked in this year’s survey was: “Have you incurred extra costs due to conflicting or improper code interpretations on a construction project completed within the past three years?” Forty-five percent of respondents answered “Yes.”

This question was followed by a question asking about the cost of such issues: “Within the past three years, what percentage of construction funding was due to citations you received during surveys?” The average response was 7 percent.

These numbers may seem high, but Joe Sprague, FAIA, FACHA, FHFI, principal and senior vice president of architecture firm HKS in Dallas, says they do not surprise him.

“Each state has their own compliance requirements, and you have different levels of enforcement. Some states have a lot of enforcement staff, and some don’t,” he says. “And that’s not even addressing the inconsistency of application. One authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) might view something as a violation, and another one may not. So 45 percent [reporting having incurred extra costs] does not surprise me at all.”

Sprague touches on two compliance issues in his comment: controversial interpretation of codes and multiple, sometimes conflicting, codes affecting a given project.

The ASHE construction survey included an open-ended question that invited respondents to share stories of compliance problems, and many did so. Below are two responses related to questionable interpretations of codes:

- “[This] issue related to a new construction mixed-use occupancy of business and health care. [The] AHJ plan review approved the two-hour separation, but [the] AHJ field inspector took issue and would not approve the construction as designed and approved. Rework cost the organization approximately $65,000 and extended occupancy by six weeks.”

- “[Regarding the] fire alarm in an attic area, one code official interpreted it one way in the design, [but] when in the field for inspections, the inspector interpreted it a different way, and it cost us approximately $14,000 [to correct].”

One survey respondent also shared a story about conflicting requirements:

- “The differential pressure between patient isolation rooms and anterooms per California Mechanical Code were not in alignment with Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) requirements.”

The money and energy spent dealing with conflicting codes and misinterpretations is money that is not being spent on patient care, of course.

Dealing with compliance

How do health care construction leaders deal with the compliance problems? For one thing, they pay consultants. One of the questions in the survey was: “Over the past three years, what percentage of design funding was spent on consultants for compliance issues?” The average was 13 percent.

One survey respondent related a story about consultants trying to interpret a code issue regarding a renovation: “[The] smoke evacuation system was to be upgraded to current standards due to a renovation in an adjacent space. There was a lot of confusion on whether the smoke evacuation system actually required an upgrade since the renovation only touched a small portion of the atrium that was being served by the system. Numerous consultants were engaged at great cost to the organization.”

But there are other ways to deal with compliance issues.

Tushar Gupta, managing principal in the Houston office of architecture firm EYP, has dealt with many compliance issues in his career in health care architecture. He believes that jumping on problems early, and having frank conversations with the AHJs, can help.

“The earlier you can get on a problem, the better,” Gupta says. “The key is communication. We have sometimes been able to overcome these issues because of direct conversations with the AHJ. We just say, ‘This is what we’re dealing with.’ Sometimes you will be surprised that the code officials welcome that conversation from the design professional. They welcome the opportunity to come to a consensus conclusion.”

John Wilson, AIA, CHFM, SASHE, director of planning, design and construction for Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas, experienced constant compliance issues while Parkland built a $1.3 billion replacement hospital across the street from their existing building. He practiced what Gupta suggests: regular conversations with the AHJs about compliance issues.

“I know when there was a question about compliance, a lot of times we would go [to the AHJ] and say, ‘This is why we did it that way,’” Wilson says. “And as long as we could show what part of the code [led to our interpretation], it was accepted.”

About this survey

SPONSORED BY

Health Facilities Management (HFM) and the American Society for Healthcare Engineering of the American Hospital Association surveyed a random sample of 3,848 hospital and health system executives to learn about trends in hospital construction. The response rate was 6.8 percent. HFM and ASHE thank the sponsors of this survey: ISAVE Team, Premier Inc. and STI Firestop.

Sprague concurs: “My experience is that if you sit across the table from the AHJs, they know the code and how to apply it. It depends on the issue and the person, but for the most part, my experience is that they’ll listen to you, and if you can convince them that the design supports the intent of the code, they will support you and give permission.”

In order to have those constructive conversations with the AHJs, however, one needs a solid knowledge of the standards, Flannery notes. And it pays to be diplomatic.

“Having a good foundation of the codes can help in this area,” he says. “These types of things always come up at a moment’s notice. You’re out there, and the AHJ says something, and you have to have a feel for whether it sounds right or not. You want to be able to say, very diplomatically, ‘That’s not quite how I remember it — can you show me where in the code it says that?’”

“Nearly all of the regulations allow for equivalency or alternate means or methods,” Beebe adds. “If you can work with the AHJ and show how the design is ultimately better than what is called for in code, there is room within the regulations for them to accept it.”

Fortunately, the problem of conflicting codes has diminished in recent years, due in large part to ASHE’s advocacy efforts in that regard. Members of the group working on the ASHE Unified Code Project have been systematically submitting change proposals regarding specific code items during the revision cycles of the codes and guidelines promulgated by FGI, ASHRAE, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses and others.

For example, the 2018 editions of the aforementioned codes are largely aligned. That effort took about three years just to get the code development cycles synchronized and to take care of many of the large issues. The work continues, removing even more inconsistencies and ensuring that even more conflicts aren’t introduced.

“It’s much better today than it was even just five years ago,” Beebe says. “But we’re still working on it.”

Projects underway

The volume of hospital construction and commensurate budgets are up from previous years, according to several questions on the survey.

For example, 23 percent of respondents said that they are currently renovating or building acute care hospitals, and 22 percent said they plan to do so within the next three years. This compares to 20 percent and 18 percent, respectively, from the 2018 survey.

“We are definitely seeing trends in that direction,” Gupta says. “I think there are several things going on. The first is steady renewal of older facilities to incorporate latest technology. Second, we know our baby boomer generation is very sophisticated — they know what they want. As they get into the health care system, they expect the best patient environment possible. On the academic medical centers side, they are dealing with more high-acuity patients resulting in a greater demand for specialized medical equipment and critical care beds.”

Specific areas

The survey also drilled down into the specifics, asking respondents where construction, renovation and replacement was happening in their hospitals.

One part of the hospital campus that is seeing more activity this year than last is the central energy plant — 9 percent of respondents are building new or replacement plants, or renovating plants, this year; and another 14 percent plan to do so within the next three years. This compares to 5 percent and 9 percent, respectively, in last year’s survey.

“With an aging infrastructure that increases risks to patients and advances in technology in the central plant, more facilities are seeing the advantages of building new or replacement plants and/or renovating existing plants,” Flannery says. “Especially when these projects can provide a return on investment based on reducing energy consumption.”

Among specific building systems, a large number of hospitals are investing in their air handlers/ventilation. The survey showed that 34 percent of hospitals are replacing or upgrading their air handlers/ventilation in the next 12 months, and another 11 percent are doing so in 13 to 24 months.

Beebe hypothesizes that the number of HVAC upgrades and replacements is high because of new requirements in certain hospital departments.

“We might be seeing the uptick because of projects on the boards related to upgrading existing compounding areas, and complying with new USP 797 sterile and 800 hazardous compounding areas, which have intense HVAC requirements,” Beebe says. “And I think upgrading the HVAC is one of those things we are always doing. Good, quality clean outside air is important.”

Another area that is seeing growth is plumbing fixtures and piping. Nearly 22 percent of respondents said they are currently replacing or upgrading those items, and another 5 percent are planning to do so in 13 to 24 months. That compares to 15 percent and 7 percent, respectively, in the 2018 survey.

“The growth in plumbing fixtures and piping could be the result of several factors,” Flannery says. “Hospitals might be adding more water-saving devices in light of drought conditions in some parts of the country. And some hospitals might be redoing their plumbing in response to the recent outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease, such as removing dead-end pipes or decorative water elements like fountains.”

In the technology area, 28 percent of respondents noted that they are replacing or upgrading security systems in the next 12 months, compared to 20 percent who said that last year. Interestingly, interest in telehealth systems seems to have slipped: Last year, 4 percent reported they were currently replacing or upgrading their telehealth systems, but this year only 2 percent said that.

After construction

More than a quarter of hospitals do not commission their finished projects, according to the survey results. Only 72 percent said they plan to do so this year, compared to 74 percent last year and 70 percent the year before.

However, Beebe notes that the survey may not be capturing the true situation. Hospitals that have recently completed only uncomplicated projects may report that they don’t commission.

“There is an expense to commissioning, and there are some projects for which commissioning just isn’t necessary,” Beebe notes. “If it’s a very simple project where you’re just moving a few walls or repurposing an area, you might not commission it.”

For major elements, however, commissioning is always advised, Sprague says.

“I would say that any major system in the construction project has to be commissioned to ensure the institution that it will operate as designed,” he says. “We recommend to all of our hospital clients that commissioning is an essential part of the process of planning, design and construction.”

Ed Avis is a freelance writer based in Chicago; and Jamie Morgan is editor of Health Facilities Management.