Facility master planning 101

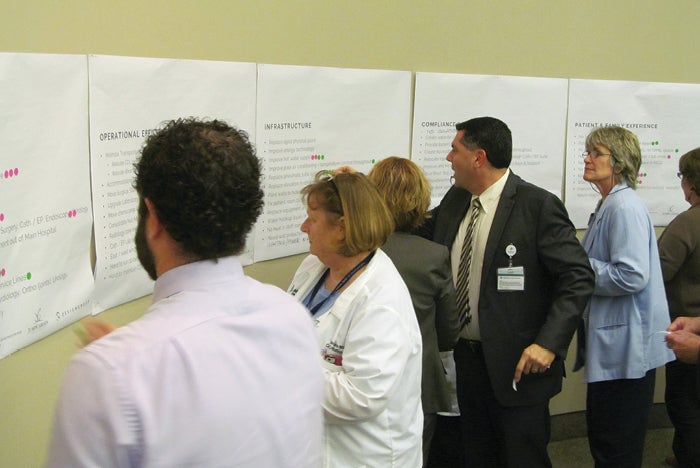

A workshop with multiple constituents can develop guiding principles.

Image courtesy of Sheila Cahnman

Hospitals and health systems are increasingly challenged to justify facility replacements, expansions and renovations based on sound strategic planning and budgeting. In the past, facility projects grew from the immediate wants and needs of departments, often tied to physician recruitment or donor interest.

Many projects were not properly vetted or prioritized considering longer term operational and financial objectives or correct location for campus transformation. In this age of declining health care revenues and need for increased productivity, every dollar must be well spent and every new or renovated square foot well planned.

The evolution of multihospital health systems has further complicated master planning. System strategies may include the shift of outpatient care to lower cost off-site settings or consolidation of services to certain campuses. Expansion of services could involve leasing space, joint ventures or investment in technology that enables care delivery in nontraditional settings, such as telehealth.

It is important for health facilities managers, architects and engineers to understand the fundamental process of strategic facility master planning and how it informs future development.

When properly executed, facility master plans support the goals and objectives of the health care provider by anticipating and preparing for the future, extending the useful life of buildings and minimizing disruption from unforeseen industry change. This, in turn, provides a framework to judge and define upcoming project requests.

Defining a facility plan

In a 2009 white paper on strategic facility planning, the International Facility Management Association defined a strategic facility plan as “a plan that sets strategic facility goals based on the organization’s strategic (business) objectives. The strategic facilities goals, in turn, determine short-term tactical plans, including prioritization of, and funding for, annual facility related projects.”

Once these goals are identified, the facility master plan or campus master plan provides the physical framework, including “site-specific integration of programmed elements, natural conditions and constructed infrastructure and systems.” For instance, strategic business objectives may support development of a new medical office building on campus.

The strategic facility plan will develop the project scope, including approximate size, departmental program and budget based on anticipated patient volumes, service line market and operations. The campus master plan will evaluate the site location and configuration of the buildings, including required adjacencies and potential physical constraints and potentials.

In the current dynamic health care climate, master plans are typically developed every five years to capture changes in business strategy, usually looking forward at most 10 years. As health systems merge, a master plan may be key in assessing facilities and determining how multiple campuses can support one new mission. Master plans can be refreshed as often as necessary to reflect major changes affecting the facilities.

Strategic analysis

The best master plans are based on strategic business planning and data analyses that will affect the development of facilities. In some cases, a business plan and market analysis are already developed that outlines strategy. If not, this may be completed while the rest of the facility assessment is underway.

Short- and long-term external conditions are identified affecting health facility planning based on historical data, trends and future growth opportunities at the facility and system level. This analysis may be completed internally, by health care specialty consulting firms or in-house teams at larger health care architecture practices. It may include:

- Demographic profiles of a hospital’s service areas: primary, secondary and tertiary that define the age, income and type of patients served.

- Use patterns and population health demand by service line that can forecast what services will grow or shrink in the future.

- The ambulatory services deployment strategy that looks at where outpatient settings are most appropriately located.

- Key economic drivers by geographic market that may affect patient population and utilization.

- Community and cultural impact, preferences and issues that may be less tangible.

- Opportunities for growth, including increasing market share.

- Physician recruitment plans for growing service lines.

- Impact of new technologies that could optimize services.

The strategic business plan then builds a case for responding to health care conditions. The results are patient volume projections and a gap analysis by service line or department that will help identify future space needs or current deficiencies.

The volume projections will later be used to develop key room counts that generate departmental square footage benchmarks. For instance, a business plan may identify a market demand based on demographics for more orthopedic services that will generate a need for more beds, or diagnostic and treatment services.

The projected patient volumes will be analyzed to create departmental requirements and determine which other clinical services will be affected. Space needs may encompass more beds, operating rooms, imaging and physical therapy.

Existing facility assessments

The facility assessment will inform planning by creating an understanding of facility and campus potential and limitations. When assessing an existing facility, the first step is to accumulate previous documentation that can assist in understanding the physical environment.

These may include The Joint Commission statement of conditions, capital asset inventories, previous master plans and patient experience surveys. Adjunct studies for infrastructure, engineering, information technology, medical equipment, site and civil engineering, parking, wayfinding and security assessments are also helpful.

The master plan level facility assessment may rely on previous facility condition assessments but in most cases is not a comprehensive review of building components. For instance, an analysis of exterior enclosure may clarify building lifespan but is not typically conducted as part of master planning. If previous studies are lacking, they may be accomplished parallel to the master planning effort.

Meanwhile, departmental surveys and walk-throughs appraise fitness in multiple areas. Again, this is meant to be a brief overview, not a comprehensive report. Ideally, departmental directors or managers complete short questionnaires in advance offering their perspectives on any facility deficiencies affecting clinical and functional operations, technology, and patient and family experience.

This forms the basis of discussion when touring departments. The departmental tours allow planners to further understand existing conditions as well as evaluate location and adjacencies, functional layout, technology, code compliance, infrastructure and overall image. Some common evaluation tools to judge departments include numerical rating systems, matrices based on topic or color designations such as “red, yellow, green” to give a quick “poor, fair, good” snapshot.

The result is a high-level description of each department’s attributes and deficiencies and renders opinions on which are most in need of renovation, growth or replacement. This is further substantiated by benchmarking studies.

Benchmarking of data provides a measure of the health facilities’ effectiveness compared to standards or best practices. Two widely used benchmarks are patient volume per key room and departmental gross square feet (DGSF) per key room. Evaluating each department’s existing square footage, there can be a comparison of both current and future space needs based on workload, staffing, and anticipated growth or operational improvement.

Take, for instance, an emergency department (ED) with a projected patient volume of 14,000 visits. If a planning team uses the benchmark of 1,400 visits per treatment bay, it can assume 10 treatment bays. If the team then assume a benchmark of 600 DGSF per treatment bay, it can initially size the ED at 6,000 DGSF for high-level planning purposes.

Or, conversely, an existing ED can be evaluated using these benchmarks. Departmental benchmarking can identify space deficiencies and right-size departments for future planning. Further patient flow analysis can substantiate utilization by looking at actual throughput and lengths of stay during space programming.

Unfortunately, there is no comprehensive data source for either of this type of benchmark, though planning consultants keep their own repositories.

Some available sources include the “Space Med Guide” by Cynthia Hayward at, the online Veterans Administration (VA) and Department of Defense (DOD) design standards at, which offer benchmarks for some departments. Some clinical organizations, such as the American College of Emergency Physicians, also provide benchmarking information for their departments.

Development of guiding principles can further help in prioritizing facility needs through definition of goals, strategies and objectives. These principles are written aspirations for how the facility may improve such things as operations, clinical practice and patient experience. They serve as a guidepost for judging the importance of different facility proposals.

Guiding principles can be developed through discussions with high-level administrators or through a workshop with multiple constituents based on issues gleaned during the facility assessment. Ultimately, the facility planner will present all the facility needs and opportunities to a leadership group, which will then rank potential initiatives based on these principles.

Typical guiding principles include items such as enhancing operational efficiency, better wayfinding for patients and families, improving safety and reduction in hospital acquired infections, revenue enhancement and a new external image to the community.

Whenever possible, these goals should be measurable. For instance, a percentage improvement in HCAHP scores would be one measure of the effectiveness of patient experience initiatives. When the strategic facility plan is complete, there should be clear direction and consensus on the size and scope of what physical improvements or new construction are contemplated and order of priorities for capital investment.

Campus/facility master plan

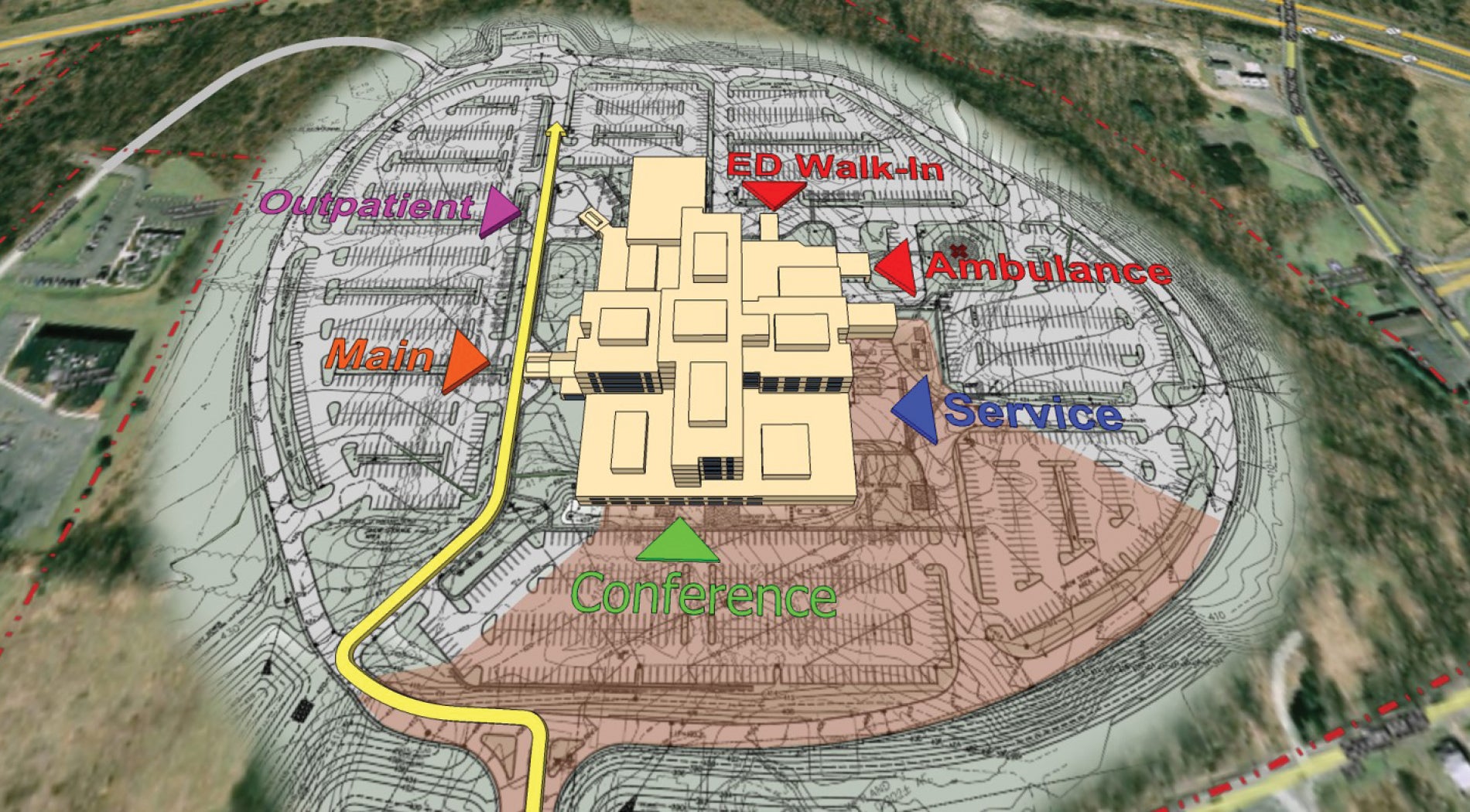

Once priorities have been set, the next step is to convert these strategic facility plans into actionable scenarios, creating physical planning options. Most master plans will develop projects for the next one to five years with long-term strategies upwards of 10 years. Options are evaluated on “guiding principles” criteria developed between the client and consultant but also include best adjacencies: staff, material, patient and family flow, and ease of phasing.

The best options allow for futureproofing (see sidebar, page 41). High-level cost modeling is completed to provide an order-of-magnitude comparison between schemes. Usually, at least two but no more than five options are developed for consideration.

Once the final option is approved, a more detailed capital need and implementation strategy is developed. The project cost model will include construction costs, equipment and furnishings, soft costs and escalation based on projected phasing and may include a cash-flow analysis. The health care organization can then use this information to calculate their return on investment.

The final facility master plan documentation package typically includes the following for one or more locations:

- Facility assessments define all the existing conditions at a high level to form a basis for decisions related to the physical plant.

- Planning guidelines verbalize why and how future changes should be developed.

- Functional plans indicate how different service lines can be zoned within a building and their relationship to each other.

- Departmental level space programs quantify the size of each department both existing and in the future to form the assumptions for space planning.

- Campus and site development plans create zones for expansion considering vehicular site access, building entries and open space.

- The final master plan includes the recommended solution and other reviewed options with phasing.

- Any adjunct studies, including engineering infrastructure, security and parking, are incorporated if important to development of the master plan.

- The cost model and phasing schedule as defined above forms the basis for financial decisions.

- Continually changing

Health care is continually changing, but today the crystal ball is even more unclear.

Key health care trends that will affect facility planning in the next decade will include rapid advances in technology, new models of clinical care, greater service efficiency, patient centeredness and family empowerment while costs increase and reimbursements decline.

Major disruptors such as governmental policies and new outside players from the retail sphere are hard to predict.

Facility master planning should create a framework based on key planning goals that can allow flexibility and create value when future configuration and growth potential is uncertain.

Sheila F. Cahnman, FAIA, FACHA, LEED AP, is president of JumpGarden Consulting LLC, Wilmette, Ill. She can be reached at sheila@jumpgardenllc.com.

This feature is one of a series of articles published by Health Facilities Management in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects.