Design simulation saves millions, reduces clinical risk

Detailed design mock-ups of frequently used spaces reduced unnecessary project spending at the Arthur M. Blank Hospital.

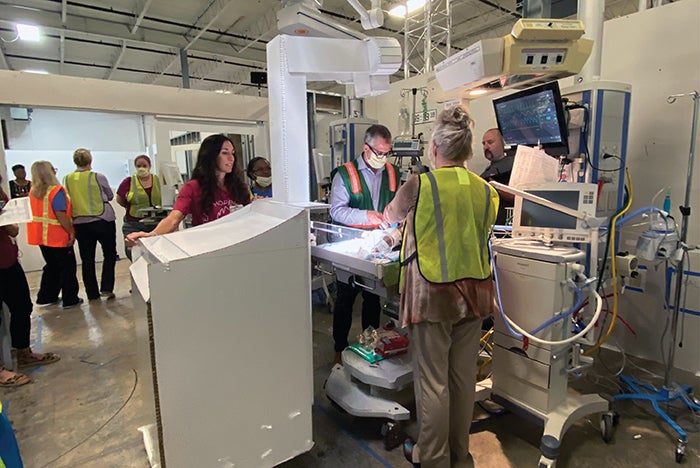

Image courtesy of Nora Colman

When Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta opened the new Arthur M. Blank Hospital in 2024, it did so with confidence that its team had designed the safest possible facility, thanks to the extensive use of simulation-based hospital design testing (SbHDT). The yearlong simulation identified 722 design issues prior to construction of the $1.5 billion project. By mitigating issues through design changes, SbHDT helped the system avoid more than $90 million in late change orders.

The purpose of simulation is to demonstrate work as it is actually done by the people delivering care, explains Nora Colman, M.D., a critical care medicine physician at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and assistant professor of pediatrics, pediatric critical care medicine, at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. Colman served as a simulationist on the project. “If you design something that doesn’t work for a nurse, doctor or respiratory therapist, we will work around it nbsp;— and that workaround, often a deviation from best practice, is where your margin for error occurs,” she says.

While virtual reality can better help clinicians interpret 2D drawings, simulationists determined this modality to be too limited in engaging multidisciplinary teams in understanding the complexity of care. Instead, the health system rented a 100,000-square-foot warehouse and created detailed mock-ups of hospital designs out of cardboard. Because the team couldn’t simulate every aspect of the 19-story facility, they focused on high-acuity and frequently used clinical areas. Simulationists worked collaboratively with the architects, general contractor and facilities teams to accurately configure 15 clinical areas.

More than 800 clinicians navigated the “cardboard city,” participating in 146 scenarios over 40 days of testing. Simulationists then led a multidisciplinary team in the use of a failure mode and effects analysis through which stakeholders objectively identified and scored the impact of each latent condition on patient and staff safety. The facilities team determined the labor and material costs associated with each change.

Among other issues, the simulation process determined that the lack of standardization in the MRI suites would lead to an excessive “cognitive load” on clinicians who had to remember to optimally position equipment in relation to the magnetic field as they moved from room to room. “We basically redesigned the entire MRI suite,” Colman says. “Had we done that after construction, it would have been cost prohibitive at more than $8 million.”