Flexible and adaptable hospital MEP systems

The Baptist Health Care Brent Lane campus in Pensacola, Fla., integrated adaptable and flexible strategies to provide a design centered around value-added goals that embraced the future.

Rendering courtesy of Gresham Smith

Given the ever-changing health care landscape, it is vital that hospitals and health care facilities, regardless of scale, functionality or acuity level, are designed to allow for future flexibility and adaptability that supports growth and change.

When looking to design for future needs, cost (and, most often, first cost) is a major driver in any decision-making process for health care owners, operators, architects and engineers. Therefore, when evaluating opportunities for future flexibility and adaptability, mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) systems historically have not been considered viable options because of budgetary limitations. Moreover, the incorporation of flexible and adaptable strategies has not always been a priority when it comes to the design conversation.

In recent years, the emergence of new environment-of-care protocols (e.g., hybrid operating suites and acuity-adaptable med-surg units), the rapid evolution of technology (e.g., imaging and electronic health records) and the migration of service lines outside of the immediate hospital environment (e.g., ambulatory surgery centers) have created a push for flexible and adaptable solutions.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic brought about a new paradigm that compelled health care facilities to rapidly evaluate and implement new care delivery protocols while increasing their capacity. It seems that almost overnight, the conversation on flexibility and adaptability was upgraded from a push in specific design scenarios to a major shift that applies to more health care facilities and their functions.

Within this new landscape, to work more safely, effectively and efficiently, health care facilities, architects and engineers alike are confronted with a key question: “How do we ensure that existing and future health care spaces become more flexible and adaptable, especially from an MEP systems standpoint?”

Short term vs. long term

Traditional thinking about flexibility evokes a sense of limitation controlled by code, administrators and red tape. When thinking beyond that, however, a health care facility is capable of far more than might have originally been envisioned.

For this article, flexibility can be defined as a process that can be implemented quickly and modified with ease. It includes strategies frequently put in place by caregivers to improve both processes and efficiencies, like safety protocols that were implemented by nursing staff during the pandemic — for example, doffing areas, intravenous drips, machines designated immediately outside patient rooms to reduce the spread of infection and temporary tents erected in parking lots to ease emergency department burden.

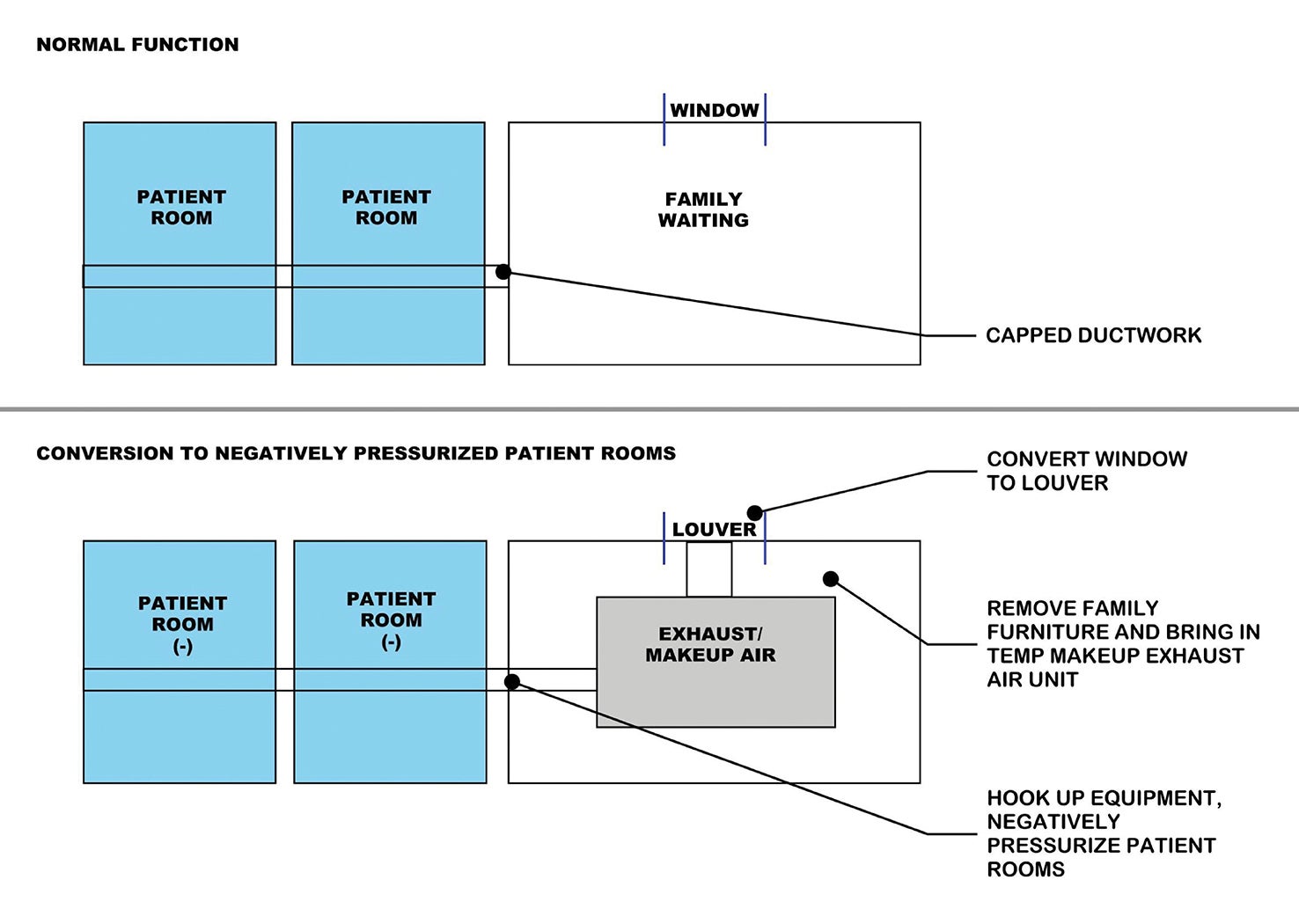

Flexibility also includes building elements that are inherently modular, like surgical booms that offer various configurations and support future innovations in surgical procedures, or hybrid operating rooms (ORs) that boast multiple care-delivery models. Portable mechanical equipment capable of increased air changes and reverse pressurization is yet another flexible building element that is modular in nature.

The use of booms within operating rooms at McLaren Greater Lansing Hospital offers the flexibility of easily adapting ORs to accommodate procedure needs over time.

Photo by John D’Angelo

Often, flexibility strategies can inform a health care facility’s long-term needs, as they offer insights into untapped operational opportunities — especially those mitigations implemented by hospital staff to make spaces work better and smarter for them. This is where adaptability comes into play.

Adaptability is a longer term view of available solutions and requires more planning to implement. It not only looks at current needs but also potential future needs and how they can be addressed. For MEP systems, this could mean adding redundancy to an air-handling unit (AHU) or upsizing medical gas systems to provide additional medical gas outlets, which requires upsizing distribution systems and storage tanks.

It can also involve increasing electrical systems to provide additional emergency power, which means upsizing distribution systems like conduits, duct banks and electrical rooms, and potentially generators and fuel storage tanks. It is important to acknowledge that these issues don’t just impact architectural space but the entire network of space that services these areas. These concepts are not limited by scale or project phase and are a worthwhile investment in the future of health care design.

Getting in front

Cost is often an obstacle when it comes to implementing flexible and adaptable design strategies.

Recent events, along with major innovations in patient-care protocols and technology, have exposed limitations in hospitals designed without flexibility and adaptability. This is evident when it comes to earning reimbursement for care and services provided, especially in value-based and merit-based incentive reimbursement models.

Prior to the pandemic, health care facilities typically opted to design a brand-new building or undertake an extensive renovation to meet their immediate needs given the stability of the construction environment. For example, if a hospital experienced an upward trend of inpatient visits, its first inclination would be to add more inpatient units. It was relatively easy to think about additional capacity in an AHU or a redundant chiller or generator as line items that could be eliminated or deferred to a future project to reduce the immediate cost. Today, faced with escalating construction costs, supply chain constraints and workforce shortages (especially in the health care arena), owners, architects, engineers and operators are more likely to evaluate the first cost of identified MEP systems in relation to other criteria for a more informed decision.

Additionally, future costs of construction along with coordination issues associated with MEP (e.g., connection to existing systems; routing of ducting, piping and electrical bus ducts; implementation of infection control; and temporary life-safety mitigation plans) are all disruptive and create a veritable domino effect in health care facilities that can result in extended service line downtimes and associated losses in revenues.

Of course, there is no definitive timeline for when a health care facility’s needs will change. What is known, however, is that its needs will change over time. It is also known that MEP systems are often rigid and expensive to retrofit and cause significant disruption if they need to be retroactively modified.

The headwall system at McLaren Greater Lansing Hospital in Michigan is designed so it can be easily dismantled and services can be added, including medical gas systems that can be capped, modified or reconfigured without a major renovation.

Photo by John D’Angelo

So, while it may be easy to decide against MEP upgrades now, deferring the decision may be more costly and disruptive in the future. Expanding a hospital’s function isn’t just a matter of physical space or even the use of space. Tied to that space is a complicated set of systems that have the power to significantly disrupt hospital functions and increase project budgets.

Making significant modifications to an operating health care facility creates an equally significant challenge. Considering the current environment, and given the constraints mentioned, it is more affordable to do the work now, or at least put processes in place to limit any downtime associated with future upgrades. For example, if a mechanical room wasn’t originally designed with enough space for additional AHUs, then architectural space will be compromised, which may impact patient-care areas. Therefore, thinking ahead and putting soft spaces around mechanical rooms alleviates some of the disruption associated with construction.

Ultimately, when examined from a holistic viewpoint, it becomes clear that any initial concerns related to the incorporation of flexible and adaptable strategies are far outweighed by the future benefits they’ll yield.

Just like Legos

Lego toys allow children to take multicolored bricks and build just about anything they can imagine. The possibilities are seemingly endless, as children can mix and combine different pieces of different sizes to make something completely new each time.

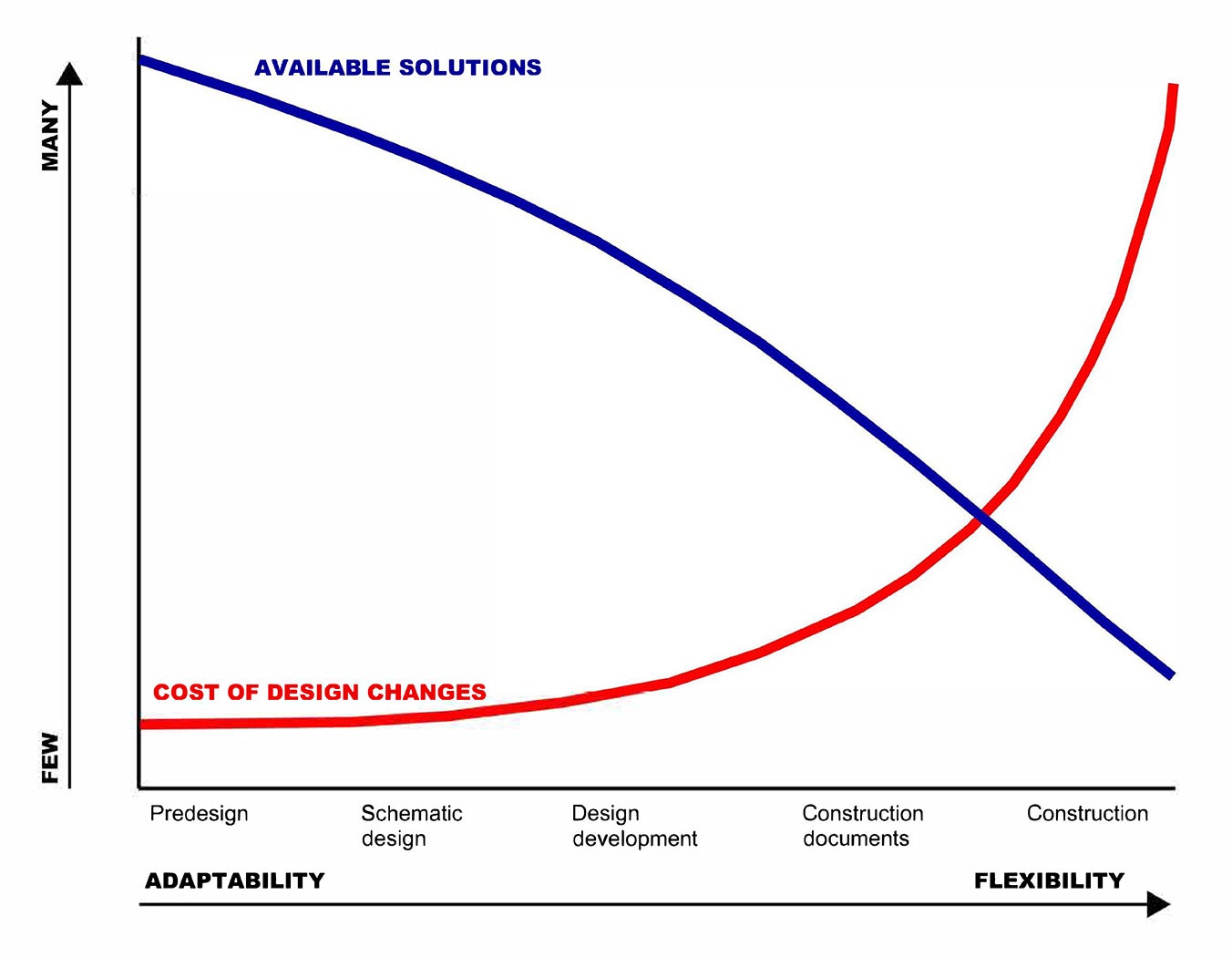

Like Legos, flexible and adaptable strategies don’t rely on a one-size-fits-all approach and are designed to be easily scalable to fit the size and scope of any project. They can also be incorporated into the design and construction process in many ways and during any phase. However, the earlier they’re incorporated, the less impact to budget and schedule they’re likely to have.

To have the most positive impact, flexible and adaptable strategies need to be intentionally incorporated into a project. Therefore, it’s important to fully evaluate the project’s needs and scope to determine where available strategies can be included.

When considering the incorporation of flexible MEP strategies during design, attention should be given to those items and elements that can be modified or changed with ease. Oftentimes, these strategies are most applicable in environments where one may need to react quickly and with short preparation times.

Examples of this strategy include moving equipment into a space to increase air changes, adding fans and connecting to existing ductwork, creating temporary patient spaces, creating triage space in parking lots or support areas, bringing in additional generators for increased emergency power capacity, or bringing in bottled water in the wake of a flood or natural disaster that’s disrupting access to domestic water.

These strategies are not one-off solutions. Not only can they support the immediate needs of a facility and provide a framework that addresses a pressing need, but they can also inform a facility’s planning and improvement approaches.

Increasingly, hospitals and health care systems are seeking a degree of flexibility in terms of how to best address fluctuations in patient capacity, acuity and staffing availabilities. Spaces that can be adapted as needed would be advantageous, such as patient units and alternative treatment areas that can flex into isolation and intensive care unit rooms. This approach requires that the spaces meet the code of the higher acuity space. This includes additional air changes and pressurization, which means more outdoor air, more enhanced building controls, more gases and a significantly higher operational cost.

Adaptable infrastructure strategies include utilizing capped connections for a future chiller as a hospital expands.

Image courtesy of Gresham Smith

This is where adaptable strategies enter the picture again. Adaptable MEP strategies can be referred to as a “Lego baseplate.” In other words, they are the vital foundational elements that can be added, swapped out or reconfigured to support a longer-term solution connected on a larger scale. Beyond the patient rooms, other adaptable MEP strategies include but are not limited to:

- Strategically locating stacked storage rooms that can later be converted into a shaft that connects future rooftop unit central energy plants that support the addition of future equipment and easy expansion.

- Capping utilities like natural gas, chilled water and heating hot water piping lines above the ceiling in an office or conference room so that minimal renovation is required in the future when converted into a patient space.

- Slightly oversizing an electrical or independent distribution frame or main distribution frame room to accommodate an additional panel or rack to support a future digital OR.

- Allowing space in a central energy plant for future equipment (e.g., chillers, pumps, boilers, cooling towers, generators, fuel storage and electrical).

During construction, while flexible and adaptable strategies are harder to implement, they are still possible. They are most easily envisioned when looking at phasing. Because hospitals need to remain operational during construction, contractors will utilize flexible strategies to keep their work on schedule and maintain hospital function. For example, air handlers can be brought in and set up temporarily on-site, which can serve the space until a more permanent solution is constructed.

What is crucial during this period is bringing all parties together early in the design phase. From there, they can discuss the project needs and determine a solution that they all agree upon. The difference between construction-phase flexibility and designing flexible and adaptable hospitals is the degree of specificity.

For example, when a contractor is looking for a flexible solution, the floor plan (i.e., the end goal) is available. Creating an adaptable building, however, is far more fluid.

Finally, more health care systems and their affiliated partners are voluntarily signing on to climate-related pledges. This increased urgency to address climate change has brought about a renewed focus on sustainability and a building’s energy performance. Beyond improving a facility’s overall energy use intensity, indoor air quality or lighting power density, the conversation has shifted to how to best reduce the embodied carbon footprint.

It is widely recognized that health care facilities consume an immense amount of energy. And, as such, MEP considerations play a prominent role in these conversations. A low-hanging fruit, MEP components offer many innovative opportunities with respect to how health care systems can reduce the embodied carbon footprint in their facilities.

Flexibility and adaptability

While making the case for flexibility and adaptability, it’s important to acknowledge the fluidity of tomorrow. There is no crystal ball that tells what a hospital will need in the future, but there is a guarantee that its needs will change over time.

The field of health care is rapidly evolving, and a health care facility is not limited by its architecture alone. MEP systems are an integral part of it and can either hinder or facilitate its growth. Thinking about MEP early in design, while planning for the future with flexibility and adaptability in mind, allows a health care facility to cater more effectively to the needs of the people operating within it.

Ultimately, the flexibility and adaptability continuum is bookended by concrete and rebar, which represent the most inflexible of scenarios, while duct tape and bungee cords exemplify the most temporary of solutions. The reality is, there is no right answer or perfect formula for the ideal balance of flexibility and adaptability. It boils down to what makes the most sense for a project, a facility and operations.

About this article

This feature is one of a series of articles published by Health Facilities Management in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects.

Motunrayo Badru, AIA, ACHA, LEED BD+C, is a project executive and health care architect; Elizabeth Morrison, AIA Assoc., is a project coordinator; and Johnathan C. Woodside, PE, CEM, CxA, LEED AP (O+M), is a project executive at Gresham Smith. They can be reached at motunrayo.badru@greshamsmith.com, elizabeth.morrison@greshamsmith.com and johnathan.woodside@greshamsmith.com.