Developing a strategy to support veterans’ care

The “rapid deployment health utility base” is identified by the acronym RD-HUB.

Image courtesy of the ACHA VA Task Force

All veterans should have equal access to the same high quality of care and positive outcomes regardless of gender, race, language, socioeconomic status or geographic location. Additionally, the veteran’s care experience should be consistently humane and reassuring.

To help meet these overarching goals, the American College of Healthcare Architects (ACHA), in partnership with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Construction & Facilities Management (OCFM), sought to help the VA streamline the care delivery process for veterans by understanding how the VA can achieve better results more expeditiously and within a reasonable cost by creating different systems, capabilities and facilities.

To accomplish this mission, a yearlong task force was assembled of ACHA certificants and a representative from the OCFM to answer the following questions:

- How can veteran access to care be improved?

- How will VA health care be delivered in the future?

- How can an equitable system of care be created?

- What kind of new spaces or facilities will be needed to accommodate this new paradigm?

The task force suggested that a redoubled effort of broad outreach is required. The program must include and integrate multiple formats of in-person, digital and virtual communication to serve different generations of veterans, all of whom prefer to communicate and receive care in different ways.

VA’s challenges

In 2022, the VA had 360,000 employees and more than 6,000 buildings, including 1,600 health care facilities, 171 medical centers and more than 1,000 outpatient sites. It is the nation’s largest integrated health care provider.

The VA wants to continue to transform to provide the best possible care for the nation’s veterans while being judicious about its capital outlay, ensuring that the VA infrastructure in the decades ahead reflects future veterans’ needs and not that of a system substantially built more than 80 years ago.

There remain a variety of challenges. Some of veterans’ most frequently voiced concerns include that care is not convenient or coordinated with appointments and not available on a timely basis, especially for specialty services. Also, there are a growing number of female veterans who are inadequately covered.

A substantial number of enrollees live beyond a reasonable driving time of 60 minutes each way to VA facilities. A third of the 9 million veterans enrolled in the VA health care system live in rural areas. Also, a significant number of enrollees live relatively close to a VA site but lack transportation options for financial reasons or are limited by a disability. There is also inadequate ability to serve the population of homeless veterans.

A program centered around virtual and mobile technology would provide additional health care options for veterans in both rural and urban areas by increasing access while reducing the VA facility real estate footprint, thus allowing resources to be redirected to more effective patient care.

Hub-and-spoke model

The task force proposed a tiered, four-dimensional hub-and-spoke model that adapts to the veteran’s needs from the simple to the complex, utilizing high-tech/high-touch technology to predict and deliver personalized health care services wherever veterans are located. This includes new technologies to enhance those already utilized by the VA, including telehealth, home health, distributed retail locations, robotic vehicles, wearables, tablets and portable diagnostic tools.

By utilizing technology to personalize veterans’ experiences, the VA can improve access, equity and quality as well as ensure compliance with medication protocols, reducing readmissions. This may allow building fewer and smaller buildings, and decommissioning obsolete ones, providing flexibility and a personalized approach to veterans regardless of location or economic status.

Some current technologies include:

- Smartphone artificial intelligence (AI) technologies such as skin-checking apps for cancer, vocal biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease detection and cough/breathing pattern analysis for respiratory issues. These simple AI technologies can help with detection of medical issues.

- Wearable trackers measuring vital signs such as blood pressure, heart rate and rhythms, blood glucose and oxygen levels, temperature and other vital signs. When connected to an electronic health record (EHR), a case manager can monitor a veteran’s health, and predict and possibly prevent a future health crisis.

- Apple watches and Fitbit devices can detect falls, physical activity and balance and be used for remote diagnosis and therapy. When coupled with higher fidelity electronic medical devices focused on specific issues such as heart monitoring (e.g., electrocardiogram) and breathing machines (e.g., continuous positive airway pressure), they reduce the need for travel to acute medical settings by reporting on a continuous basis through the EHR. This could be monitored by AI and reported to case managers.

Providing veterans with a choice on how they communicate with health care providers humanizes the process and respects the individual. A veteran can choose to meet a provider via a phone call, text, chatbot or video chat, physically visit a facility or even meet in the metaverse.

Veterans have difficulty traveling to medical facilities due to a variety of reasons, including lack of access to transportation, remoteness or distance from the right medical facility, mobility difficulties, work schedules/family commitments, difficulty in communicating (i.e., language and culture) and other issues. A “mobile medical vehicle” with advanced medical technology and modalities that goes to the veteran’s home could provide this necessary service or be used to set up a mobile health clinic within a community, reducing a veteran’s travel.

An unhealthy home environment can either create health issues or hamper a veteran’s recovery. An additional benefit of home care is the caregiver’s deeper understanding of the lifestyle and living environment of the veteran.

A new paradigm

The “rapid deployment health utility base” (RD-HUB) is a new paradigm for bringing primary care to veterans, expanding access to enrollees via delivery of a mobile, technology-based program that would provide home health care to veterans throughout the U.S.

Some key benefits are that it:

- Implements new technology to provide rapid delivery of health care to the patient.

- Greatly reduces the number of trips to facilities for many rural and limited-ability patients.

- Can be implemented quickly in a cost-effective manner.

An assigned care team based at the RD-HUB connects remotely or travels to veterans to provide appropriate care. This approach suggests less of a reliance on the built environment and more about a transition to technology- and mobility-based strategies. Veterans or their families do not come to the RD-HUB; instead, services come to them.

The RD-HUB is based in a building created from a kit of parts used individually or joined together to form a larger base hub to distribute health care services. It is a modular approach where one unit could be considered for a small base or more units planned for a larger base. This flexible approach could be implemented based on the services to be provided in a region or area.

Other characteristics of the model include:

Location. The RD-HUB base could be in remote areas or partnered with other existing infrastructure opportunities like a community-based outpatient center or a critical access hospital. Existing sites could function as test areas to implement the RD-HUB more rapidly. The reuse and adaptation of existing abandoned commercial spaces would save the money, resources and time needed to implement the concept.

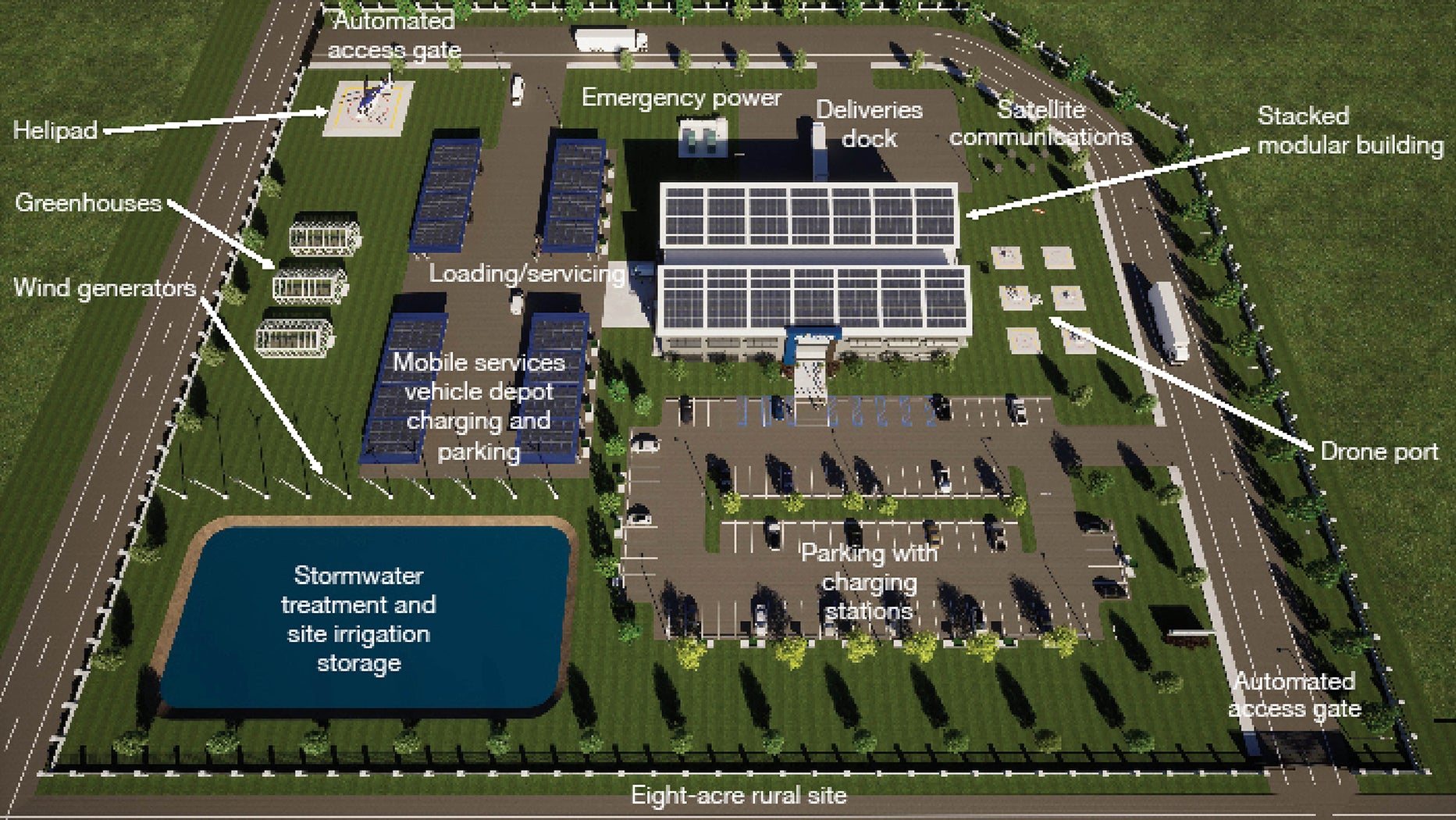

Design summary. An 8-acre site in a rural or suburban location adjacent to key roads is shown in the image above. It assumes that basic utilities, such as sanitary, water and electrical, are available and the site soils and topography are manageable with relatively low-cost site preparation and structural solutions. The design and construction goal for facility implementation is approximately six to eight months.

Building features. The conceptual building shown below is a two-level stacked modular design. Conventional construction methods are also suitable if they are the most economical choice in certain regions. The modular, repetitive components could be manufactured at central or regional plants and shipped to sites throughout the U.S., reducing overall construction costs and the need to find qualified labor. The building length and height can flex to adapt to the needs of a particular service area. This example shows a 36,000-gross-square-foot building.

The first level is designed to handle incoming shipments of medical and pharmaceutical supplies, durable medical equipment and similar items. There are also garage bays for loading equipment and supplies directly into service vans or other vehicles. The second level includes the telehealth center of excellence, base operations, communications center and information technology support as well as team administration and sometimes housing.

The proposed concept for this facility is net-zero energy and water usage and substantial on-site power generation that allows it to operate off the grid. Sustainability tactics would include consideration for embodied carbon along with the potential of relocating building components in the future.

Site features. The site supports deliveries as well as covered parking of service cars and vans, medical imaging rigs, transport buses and other support vehicles. The site also supports staff parking, satellite communications, emergency power and a helipad for emergencies.

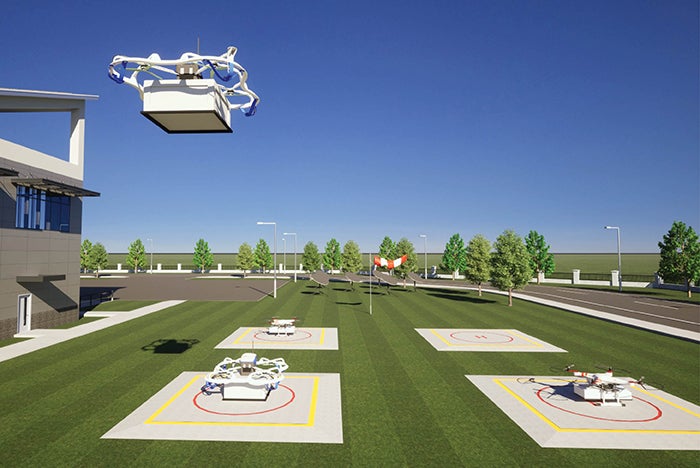

The RD-HUB would have a drone landing port to potentially deliver items directly to the veteran’s home. All vehicle areas support electric charging. Some small greenhouses could grow food to improve nutritional outreach to veterans.

Program components. The vehicle depot is a deployment hub including mobile care vans with exam and diagnostic capabilities, smaller electric passenger vans, electric cars, sports utility vehicles, motorcycles and scooters as well as drones. The depot is stocked with medications, medical supplies and any needed vehicle maintenance items.

The technology shop is a supply, education and repair location for providing devices to veterans. With a stock of tablets, wearables and metaverse devices, the shop would deliver, mail or provide technology support for veterans.

The telehealth center would provide a multi-disciplinary, patient-aligned care team. Patients would be connected to a care coordinator who has access to a variety of services and specialists, including mental health and nutrition consults. The consultation team could all be remote or co-located in a call center where staffing is available.

The pharmacy component would stock vehicles, filling and delivering medications within the local services area. A virtual pharmacist could provide consults to ensure compliance.

Stocked durable medical equipment would be distributed to the mobile service vehicles for delivery to veterans’ homes. A bioengineering representative could be dispatched to install more complicated equipment, or an occupational therapist could provide an “activities of daily living” assessment.

Additionally, RD-HUB-based behavioral health specialists could visit a veteran in their home for a counseling session, organize group sessions in local community spaces or set up a telehealth visit via a tablet supplied by the technology shop so veterans can conveniently connect remotely with providers.

When a face-to-face visit is required, the mobile vehicle and care team could treat veterans in an equipped outpatient clinic van or transport them to a community-based outpatient clinic that may be co-located with the RD-HUB.

Social workers could travel to veterans to assess their home environment and living conditions, counsel on services and help them fill out forms. As an outreach service, the RD-HUB staff could host farmer’s markets, healthy food and lifestyle events, clothing distribution, diabetes awareness and benefits fairs. The vehicle could use an existing retail parking lot as a platform for the event.

A mobile van equipped with vision and dental services could provide free screenings and education sessions, set up appointments and perform exams either in a veteran’s home or at a retail site. Vision and dental supplies could be delivered to veterans in person or by mail.

Where hiring employees is difficult, a one week, one month or longer rotation at the RD-HUB would help to staff the location for service, deployed through a centralized VA staffing service. There would be sleeping quarters, a canteen, office areas, exercise rooms, robust internet connectivity and other amenities. This model is suited to very remote areas.

The “fourth mission” of the VA is providing a response network for the nation in disaster preparedness; therefore, selected RD-HUB locations would have a resiliency center component. Acting as emergency conditions locations, they would be stocked with emergency supplies, such as water, medicine and food, and could be self-supporting in times of need.

Adapting delivery

To deliver equitable, high-quality, accessible care in the future, the VA must adapt the delivery of health care to location and needs. The system must be predictive and proactive, adaptive, flexible, sustainable and resilient, affordable, lean, collaborative and vertically integrated.

The ACHA VA task force report

The accompanying article summarizes the findings of the American College of Healthcare Architects (ACHA) Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) task force that was charged by the VA to explore new concepts and facilities to provide more equitable care to veterans. These individuals made the task force report possible:

ACHA task force members

- Clyde “Ted” Moore III, AIA, ACHA, LEED BD+C, Haskell, ACHA VA task force facilitator.

- Wayne Barger, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, SmithGroup.

- Sheila Cahnman, FAIA, FACHA, LEED AP, JumpGarden Consulting LLC.

- Anne M. Cox, AIA, ACHA, EDAC, LEED AP BD+C, WELL AP, A3C Collaborative Architecture.

- Jim Hageman, ACHA, NCARB, Alesia Architecture P.C.

- William I. Kline, FAIA, ACHA, EDAC, LEED AP, Leo A. Daly.

- Steve M. Langston, AIA, ACHA, EDAC, LEED AP BD+C, Rogers, Lovelock + Fritz.

VA Health Administration representative

- Ken Dickerman, AIA, ACHA, VA office of construction and facilities management.

The care experience must be holistic, veteran-centric, accessible and coordinated with less reliance on the built environment and more on a transition to technology and mobility-based strategies, augmented by strategically placed facilities to support mobile units.

The RD-HUB and its components would implement technology and delivery of services to veterans, reducing the need for veterans to travel. Personalized in-home health care services, technology that is provided and maintained, and close access to needed services is the success of this strategy. There would be less reliance on brick-and-mortar solutions, more reuse of existing infrastructure and partnerships with businesses to support veteran health at a community level.

In summary, a system built around the needs of those who served.

Example shows how RD-HUB can help homeless veterans

Mark is a fictional U.S. Army veteran who served in Vietnam and is living in Florida. He has suffered from chronic heart disease and diabetes for most of his adult life. Although he has no service-related injuries, complications from his diabetes several years ago resulted in the amputation of both legs below the knee. In addition to those challenges, Mark was recently diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Mark is one of many homeless veterans. He is food insecure and finds it difficult to follow a diet that won’t exacerbate his diabetes. He does not have a reliable and secure space to store his medications, and maintaining personal hygiene and physical comfort are daily challenges. With his mobility issues, transportation is one of his most acute problems. Accessible routes to the community homeless shelter are limited. Therefore, he often sleeps outside in a tent when the weather is nice. While this arrangement is challenging and makes it difficult to charge his wheelchair, it gives him closer proximity to preferred stores, banks and offices. He is on a waitlist for both subsidized housing and a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) domiciliary.

A more connected and mobile VA delivery system based on the “rapid deployment health utility base” (RD-HUB) model could mitigate some of Mark’s challenges. For instance, mobile units could be deployed to urban sites on a predictable schedule. A unit deployed near Mark’s homeless shelter would provide wound care for his legs, regular dispensing of his diabetes and cancer medication, maintenance of his wheelchair and consultation on his diet. Mental health consultations could be provided either in person or via a telehealth visit. The RD-HUB staff would coordinate access to community farmer’s markets and local grocery stores for better dietary options. Ideally, Mark would be provided with wearable monitoring devices — including for blood glucose — that are remotely monitored by the VA to help manage his diabetes.

About this article

This feature is one of a series of articles published by Health Facilities Management in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects.

Sheila F. Cahnman, FAIA, FACHA, LEED AP, is president at JumpGarden Consulting LLC, Wilmette, Ill. She can be reached at sheila@jumpgardenllc.com.