Outpatient options

The structure of U.S. health care delivery will change radically this decade and so will the facilities in which this care is delivered. The era of the full-replacement hospital may be waning and, in its place, an era of affordable, incremental growth, with emphasis on the outpatient arena will begin.

The structure of U.S. health care delivery will change radically this decade and so will the facilities in which this care is delivered. The era of the full-replacement hospital may be waning and, in its place, an era of affordable, incremental growth, with emphasis on the outpatient arena will begin.

The emerging trend bundles payments to incentivize outcomes and quality — regardless of inpatient or outpatient setting — over the continuum of a patient's experience. Management of care across a spectrum of programs, facilities and providers allows the delivery of health care services to be performed effectively under one umbrella payment for services.

Ambulatory care centers will need to be high-yield, high-outcome "process centers," with the focus on throughput. New technologies, process improvements and staffing alternatives must achieve high quality and performance. Every space must be highly utilized and flexible.

Reform and economics

Legislated health care reform and new economic realities are driving several trends that will change how ambulatory care facilities are designed.

As more hospitals merge to form new health systems, they want to direct access into new, profitable and underserved areas. Many times, these developments are started with some type of ambulatory care facility, such as a medical office building with a diagnostics center, an oncology or cardiac rehab center. In some cases, this could be the beginning of an inpatient facility with an emergency and procedural center, and 23-hour stay beds.

Health systems are seeking better financial outcomes with less capital investment, less building and in less costly square footage. Ambulatory care facilities are less costly to build when decoupled from the acute care hospital. Almost any function that can be built under the local building code business occupancy may be located out of the hospital chassis. These buildings may be freestanding, but can link to hospital functions.

Current and future shortages of physicians and clinical staff and associated higher labor expenses will drive facility and operational models that deliver care with fewer human resources, which are more feasible in the outpatient setting. There will be greater use of physician and nurse extenders — trained practitioners who can perform more routine tasks. Health system websites already are allowing for patient visit and test scheduling and result reporting, online pre-procedural tutorials and physician consultations.

Organizations that deliver better outcomes at lower costs can gain significant market advantage. Operational costs far outweigh first capital costs over the lifetime of a facility. As private insurance-market reimbursements start to resemble Medicare's compensation, Lean process improvement will become standard practice. This will allow consistent, though perhaps reduced, profits on less operating revenue.

Aggressive reduction of operation costs will lead to more novel approaches to ambulatory care delivery, including more standardization and consolidation. Evidenced-based care protocols will be enforced more rigorously as outcomes will be tracked and reported. Such government programs as Medicare and, in the future, most private insurance companies will require this reporting.

Translational research will extend out of academic medicine into community hospital venues, requiring space for more clinical trials, etc. As the range of trials expands, researchers will need more willing subjects who are not inconvenienced by traveling to major health centers. Regional health systems affiliated with teaching institutions will promote research as another way to attract patients to advertised high-quality care.

Technological advances, such as electronic health records and scheduling, telemedicine and internal control centers, fundamentally will change how patients are tracked. At home, remote technology will allow for testing and monitoring to reduce routine physician visits and follow-up. In the future, nanosensors may be remote monitors of blood sugars in diabetic patients. Biomarkers and other technologies may allow for at-home breath analysis for a number of conditions. This could reduce the number of clinic visits to only those needed for in-person examination.

Key planning components

These trends will affect the basic tenets of ambulatory facility design. The changes that will affect the following key components of ambulatory care planning include:

Accessibility and wayfinding. Outpatient services must be easily accessible. As competition increases, patients will seek locations that are close to home and have available parking or are near public transit. Many will be collocated with or near retail areas. For elderly patients, valet parking is a plus. Facilities more likely will be open in the evenings and on weekends. Zoning codes typically require four to five parking spaces per 1,000 square feet of building area.

On the interior, wayfinding is key because of the larger volume of patient movements and their potential unfamiliarity with the building. Traditionally, patients have been greeted upon entrance by a receptionist who then directs them to a central registration service. This central location often became a huge logjam as patients waited to be called. A newer trend is to preregister as many patients as possible so they can then go directly to a point-of-service, streamlining patient flow and simplifying the process. Electronic kiosks also allow patients to register at arrival without checking in.

For those not preregistered, many facilities will register at point-of-care to reduce patient registration interfaces in the building. The future may bring "smart screens" that greet patients by name and provide a full itinerary at check-in.

Waiting and amenities. The trend is to reduce the number of patients waiting to be treated. This not only creates greater patient satisfaction, but also reduces the number of seats needed.

Some organizations are testing systems that can notify patients on cell phones via text alerts when their caregiver is running late. Also, text notifications can be used in place of restaurant-style pagers to notify patients that they should report for their appointments. These alerts allow patients and families to utilize dining and retail areas while they wait rather than feeling compelled to sit near the receptionist. Patients also can utilize outdoor-seating areas adjacent to the clinic.

Consult rooms can be located strategically between the waiting areas and clinics to allow patients and families to meet with caregivers on the edge of the clinic modules without passing clinical control points. These rooms can be outfitted with more comfortable furniture and ambient lighting to decrease anxiety.

Many ambulatory centers are experimenting with more extensive food service and retailing, usually with a health and wellness theme. Besides the pharmacy, stores often include homeopathics, sleep aids, book stores and health food. In fact, one ambulatory mall includes a farmers' market several days a week.

The clinic module. In the past, ambulatory care for a hospital or health system was provided by individual physicians or physician groups who leased space in a medical office building (MOB). The physician's spaces were custom-designed and idiosyncratic. Diagnostics, such as radiography or ultrasound, were physician-operated within their practice or provided by hospitals either in or outside of the MOB setting. Clinic designs have strived for consistency and flexibility for many years in academic medical settings where the physicians are hospital-employed or part of a very large consolidated physicians' group.

The most successful clinic designs are ones that allow flexibility in use on a daily basis. Clinics are not defined by one specialty or practice but, rather, can flex with adjacent clinics to modulate the number of exam rooms needed by a practice on a given day. In some cases, clinics receive such generic names as A, B or C so different practices can change the nameplates out front when in use.

This flexibility requires that clinic modules be more universal in design and that physician office space not be embedded within the exam room areas.

Clinical support. Because there is a shortage of nurses and physicians throughout North America, an efficient layout is increasingly important. This includes reducing travel distances for caregivers by keeping supplies and computers for charting within easy access.

Usually, clean supplies are located centrally within each clinic module and then par stocked into exam rooms. To reduce the risk of infection and contamination, the trend is to limit the number of supplies, gowns and linens stored within the exam room, but have them restocked frequently. Likewise, medications can be distributed from an automatic dispensing unit per module.

To improve efficiency and exam room utilization, an intake area per module allows weight, blood pressure and other vital signs to be taken before the patient occupies an exam room. In high-volume operations, nursing support can be designated to this task. Sometimes a small blood draw area also can be located here.

Most current exam room designs include a computer either mounted on a desk or on a mobile cart. The more flexible designs allow for the caregiver to face the patient or family while entering information. This allows the physician to review data on the screen with patients so they can better understand instructions. In the future, this computer may become a handheld device.

"Hoteling" areas with shared computers allow physicians to complete patient electronic charts away from their private offices. These areas should be central to the modules but visually separate from the patient areas, and allow for acoustical privacy. As health care becomes more collaborative, shared team-meeting rooms have become more prevalent. These also can be used for patient and staff education and care planning.

Diagnostic and treatment areas. Most ambulatory care centers will include some type of imaging, stat laboratory/blood draw and pharmacy services. Imaging can range from simple chest X-rays to a full imaging center including ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and angiography at larger venues with supporting patient volumes. The modalities will depend on the type and size of clinics, with orthopedics, cardiology and cancer requiring more advanced diagnostics and others less.

Some hospital systems are including outpatient surgery and interventional suites within their ambulatory care venues. This requires special attention to state health care regulations regarding the procedures and associated anesthetics that can be used under a business occupancy and outpatient building code.

There are different restrictions on the number of patients allowed who are unable to perform self-preservation in case of an emergency. In many cases, minor procedure rooms for cases not requiring more than conscious sedation are located between clinic modules so physicians can perform procedures during clinic hours.

Research integration. Many health systems have found that the best place to engage more clinical research subjects is at the point-of-service. By locating clinical trial coordinators in semipublic locations within clinics, patients and families easily can learn about available clinical trials. Exam rooms can be used for interviews and follow-ups when not used for clinic visits. Public displays of research findings also can create interest in participation.

In academic medical settings, dry or wet laboratory research can be located either adjacent or fully integrated into an ambulatory care setting. This allows researchers, clinicians and patients to interact and bring medical advances from bench to bedside sooner. The different physical construction demands of a laboratory (including HVAC requirements) versus office building make full integration rather costly. However, joint office areas and places for chance encounters can help align research and clinical practice.

Wellness. Major medical organizations are leading the development of programs and services aimed at curbing 75 percent of our health care costs attributable to chronic, preventable diseases. In all, about 40 percent of premature deaths in the United States are caused by such lifestyle choices as smoking, unhealthy eating and inactivity. Progressive institutions are changing the paradigm by combining the best in clinical care with the most innovative wellness philosophy.

In the ambulatory environment, there will be a new accommodation for programs and services related to wellness, including educational meeting spaces, demonstration kitchens, alternative therapy settings and specialized retail stores.

Likewise, ambulatory clinics may be located more often in such nontraditional settings as shopping malls, schools or office complexes. Ease of access by either proximate parking or public transportation will be even more important.

Exam rooms and other clinical spaces are changing in character to accommodate more family members comfortably. They need more contact with physicians and clinical staff so they can help implement care plans at home, sometimes supplemented by a wellness coach. These may include not only medication and therapies, but also lifestyle changes.

Training and teaching will continue to become a more integrated element of the patient's visit to an ambulatory care facility.

Sheila F. Cahnman AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, is group vice president and regional leader of health care at HOK in Chicago. She can be reached via e-mail at sheila.cahnman@hok.com.

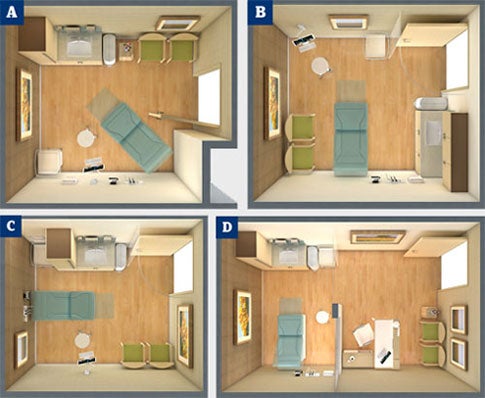

| Sidebar - Examination room options for ambulatory spaces |

|

Because the examination room is the most repetitive element in an ambulatory health care facility, every square foot must be organized carefully and accounted for to reduce overall building size and cost. Most new exam rooms are designed as same-handed: All rooms are oriented in the same direction with all doors and equipment in the same location in each room. This evidence-based design feature increases familiarity for staff and may reduce medical errors. Traditionally, exam rooms are 80 to 100 square feet; in new facilities this has grown to 100 to 120 square feet to accommodate family members. In some cancer centers, this can grow to 150 square feet if the exam rooms also are used for consultations. Diagrams A through C show three commonly used configurations for exam rooms in North America. Any of these room types can be selected based on staff preference and overall building configuration. In these cases, a physician rotates among three and four exam rooms during the day to increase efficiency. Diagram D shows a commonly used layout in private hospitals in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Particular characteristics of each room type include the following: • Exam Room A. In this layout, the patient faces away from the door for more privacy. The family can sit closest to the door for easy entry. The clinical zone is in the back half of the room, however, making the sink less accessible. The computer is mounted so the physician can address the patient on the exam table or in the chair. • Exam Room B. With the exam table perpendicular to the entry door in this design, a cubicle curtain may be required for visual privacy. The sink by the door encourages hand washing. However, locating family seating in the back half of the room could obstruct the clinicians. • Exam Room C. With the exam table facing the door, this is the least private exam room design. However, the sink is accessible at the entry and the family seating is in front of the room away from the clinician space. The computer can swing to face the patient or family for physician consults. • Exam Room D. In this configuration, the physician office and exam room are combined, allowing family members to remain outside the clinical area. Here, subwaiting areas are utilized so patients are "on-deck" to increase throughput. Sometimes in this model, two entries are provided so that physicians can enter from a separate staff corridor. |