Deferred maintenance and master planning

Master planning requires a comprehensive and strategic approach to designing and organizing facilities and services over a long-term horizon.

Image by Getty Images

Health care organizations continually face pressure to manage expenses and improve operating margins while meeting the growing demands of the communities they serve. Traditionally, those demands are driven by community growth, demographic shifts, anticipated census increases and/or changing service line complexity in various markets or regions.

In addition to these top-line metrics, health care organizations also may consider the need to harden facilities against natural disasters and cybersecurity threats, improve energy efficiency, reduce carbon emissions and reimagine the role of the facility itself.

In some cases, these considerations are discretionary, while in others, they may be mandatory due to legislative or regulatory activity. Regardless of the reason, it is imperative that health care organizations regularly conduct master planning exercises to help guide and forecast overall long-term strategic investment needs.

In parallel to this focus on the future, existing infrastructure continues to age. Deferred maintenance statistics show that a significant number of hospitals in the United States, and the mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) assets required to safely operate them, have exceeded their expected useful lives and should be considered for replacement, especially when they are no longer supported by the manufacturer.

The data further suggests that without intervention, this aging trend will continue well into the next decade, potentially creating a perfect storm of conflicting financial priorities that will challenge health care facilities for years.

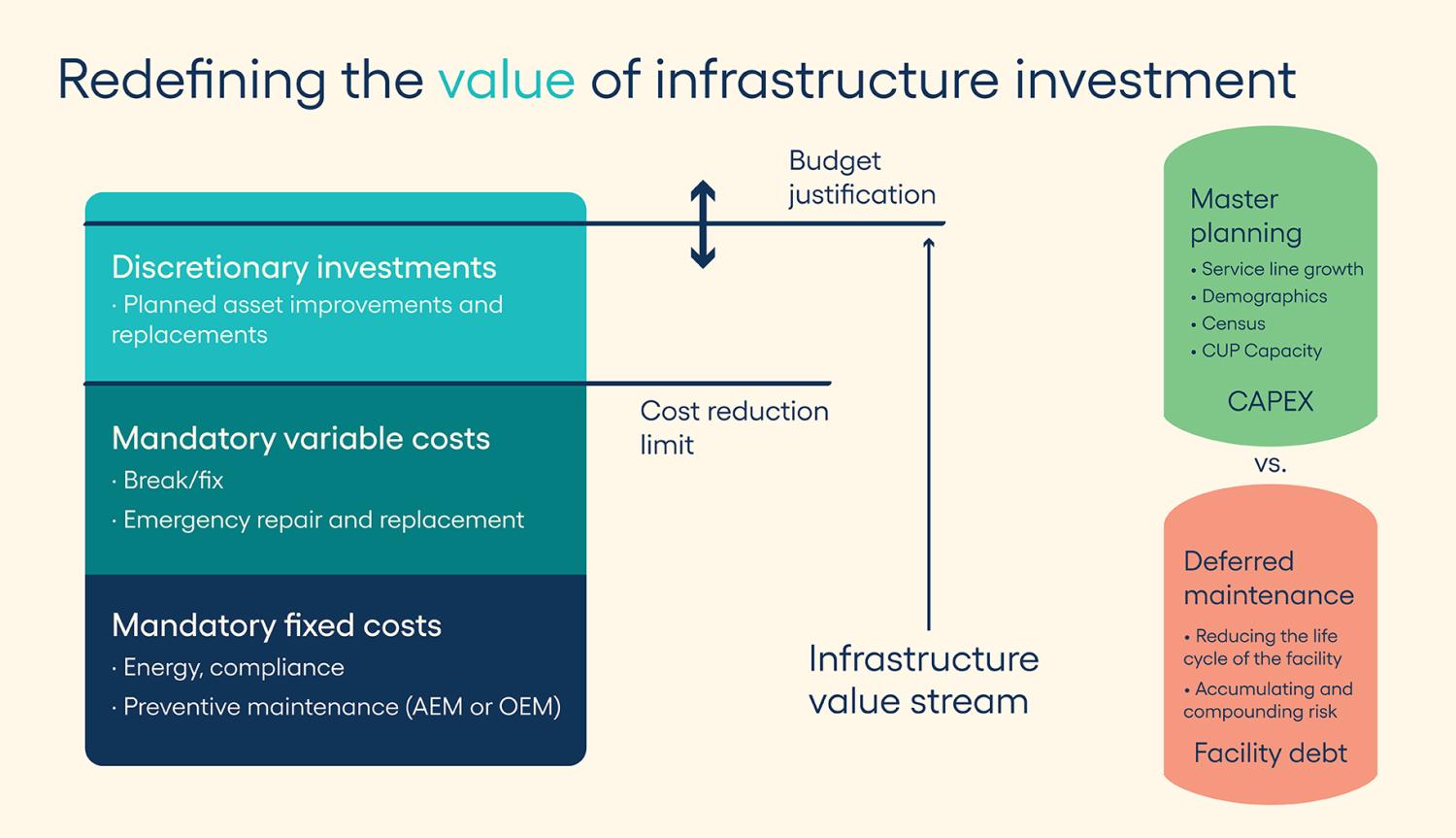

Infrastructure investment metrics may be included in master planning efforts by individual hospitals or health systems but not always, and rarely in a standardized manner. In the most extreme examples, organizations may concentrate heavily on architectural planning projects that focus exclusively on top-line growth, with only cursory inclusion of existing repair and replacement needs.

Meanwhile, the state of the existing infrastructure, even if determined to be adequate to sustain the program at the time of planning, may be one of the largest variables impacting the financial success of long-term growth plans for the organization. Consequently, it is important to include all relevant facility condition and infrastructure costs into master planning activities.

Defining master planning

Master planning in acute care settings refers to the comprehensive and strategic approach to designing and organizing facilities and services over a long-term horizon. This involves assessing current health care needs, forecasting future demand and planning the resources, infrastructure and services necessary to meet those demands.

The importance of master planning in acute care settings cannot be overstated. When properly constructed, the master plan will serve as a guideline from which many other important decisions can be vetted and aligned. Some of the benefits of master planning include:

- Resource allocation. It helps in the efficient allocation of resources, ensuring that staffing, equipment and facilities are tailored to meet patient needs. This is particularly true when changing service line requirements may alter operational performance.

- Facility design. It guides the design of buildings and physical layouts to enhance patient care, streamline operations, and ensure safety and accessibility.

- Compliance and accreditation. It ensures that facilities comply with regulations and accreditation standards, which is essential for maintaining licensure and funding.

- Adaptability. It allows health care organizations to adapt to changing environments, such as evolving technologies, patient demographics and regulatory requirements.

- Cost efficiency. By anticipating future needs and trends, it can help mitigate unnecessary costs associated with ad-hoc expansions or renovations.

- Quality of care. It can result in improved clinical outcomes through better organization of care delivery processes.

- Stakeholder engagement. Involving various stakeholders — including health care providers, patients and community members — in the planning process fosters collaboration and helps address community needs.

- Sustainability. It can promote sustainable practices in health care facility design and operations, addressing environmental concerns and resource efficiency.

In summary, master planning is crucial for aligning health care capacity and service needs with the evolving demands of the population, ensuring efficient use of resources and delivering high-quality patient care.

Understanding investment needs

To properly engage in a discussion about infrastructure investment, it is important to define infrastructure, quantify the concepts of preventive and deferred maintenance, and identify key metrics that can be used to track investment impacts. Without a level-setting of these concepts, it is nearly impossible to engage in an objective discussion of needs.

Merriam-Webster defines infrastructure as, “1: the system of public works of a country, state or region also: the resources (such as personnel, buildings or equipment) required for an activity; or 2: the underlying foundation or basic framework (as of a system or organization).” Specific to the health care physical environment, facility and utility infrastructure can be defined as the MEP assets and systems, as well as architectural elements (e.g., facades, glazing and roofing) that are required for the hospital to safely operate.

These systems are often broken down further based on risk, criticality or impact to patient care, with emergency power and life safety assets and sub-systems deemed highest criticality. Medical gas; heating, ventilating and air-conditioning; and water management assets and sub-systems follow closely in criticality to effectively manage and mitigate risks associated with airborne or waterborne pathogens. Lastly, the architectural elements of building enclosures may be deemed critical, as the failure to protect the environmental integrity of acute spaces may have detrimental effects on patient care and clinical outcomes.

To measure infrastructure investment needs, it is important to properly define metrics used to quantify aging infrastructure trends. Some key definitions include:

Preventive maintenance (PM). PM activities typically include actions performed on a time- or machine-run-based schedule that detect, preclude or otherwise mitigate degradation of a component or system with the aim of sustaining or extending the useful life and operational stability of a particular element of the infrastructure. Alternatives to PM include reactive maintenance (run to fail), predictive maintenance (PdM) or reliability-centered maintenance (RCM), each with different levels of cost and benefit. As published by the Department of Energy in Release 3.0 of “Operations & Maintenance Best Practices,” scheduled PM strategies alone can generate an estimated 12% to 18% cost savings versus reactive maintenance and significantly extend the useful life of critical assets. PdM and RCM techniques can further enhance that cost-saving benefit.

The adoption of different maintenance strategies depends on the culture and relative asset management strategy of a particular organization, with scheduled PM being typical. While some organizations are adopting PdM and RCM, many are limited by a lack of resources, staffing and/or training. This speaks to the importance of including operational and capital considerations when looking at overall health care facility infrastructure investment needs.

Deferred maintenance. This includes infrastructure assets that have exceeded expected useful life based on age, condition, operational maintenance history and/or criticality. These assets are not necessarily in imminent failure mode but indicate an accumulation of risk and should be evaluated carefully for renovation and/or replacement.

Deferred maintenance levels are typically reported based on dollar value of assets as a percentage compared to the total MEP portfolio value. In June 2021, data published by Facility Health Inc. and commissioned by the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) suggested that about 41% of MEP assets were in deferred status. In financial terms, that translated into a $391 billion national investment need over the next 10 years. Current data, based on national benchmark data tracked by Brightly, a Siemens company (which acquired Facility Health Inc. in 2021), suggests that deferred maintenance levels are trending higher and have increased to about 53% as a national average. Although not validated statistically, this dramatic increase can be at least partially attributed to the capital investment reductions enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Accurately tracking MEP inventory, along with objective age and condition performance data, is a foundational requirement for quantifying deferred maintenance levels. This data is typically collected through the performance of a facility condition assessment and then tracked in a computerized maintenance management system or strategic asset management solution to provide accurate inputs into the following metrics:

- Age of plant (AoP). AoP is most often used in financial accounting and tracking of deferred maintenance levels. While not a direct measure of physical age or condition, it is constructed as a financial ratio comparing accumulated physical depreciation (e.g. deferred maintenance) versus depreciation expense. In layman’s terms, increasing AoP trends suggest that an increasing number of assets are physically installed and remain in service even after they have been written off and fully depreciated from a financial perspective. Increasing equipment age and/or declining performance can indicate a potential higher probability of breakdown or unplanned failure.

- Facility condition index (FCI). FCI is a more common metric that utilizes the same deferred maintenance inputs and requires some level of interpretation for comparison across multiple sites. An FCI level of 0.15, for example, indicates that infrastructure deferred maintenance investment needs would equal 15% of the total replacement value of the entire facility holding that same infrastructure. According to ASHE’s “Capital Renewal Playbook” monograph published in 2018, “In practice, most consultants and health care facility leaders agree that buildings with critical functions (e.g., hospitals and surgery centers) should aim for FCIs of 0.05. For other, less critical buildings (e.g., outpatient clinics and administrative offices), the FCI target is closer to 0.10.”

Due to the invasive nature of infrastructure renovation projects, aging infrastructure metrics, such as deferred maintenance, AoP or FCI, not only indicate an increased risk of unplanned asset failure but also predict future levels of negative organizational impact if larger assets and systems must be replaced in parallel, all while providing patient care. This underscores the fundamental reason for considering the state of the current infrastructure in any future projections.

Facility condition metrics

The integration of infrastructure investment needs into health care master planning presents a valuable opportunity to enhance collaboration between engineering and architectural disciplines and to align with the stated clinical and financial goals of the organization.

Resources

Ultimately, this results in improved health care environments that are not only conducive to patient care but also sustainable and responsive to future needs. A failure to do so may negatively impact overall profitability due to revenue loss associated with unplanned shutdowns, stoppages of revenue-generating procedures and services, damage to reputation or other negative consequences.

In practical terms, facilities leaders are encouraged to secure the data necessary to objectively defend infrastructure investments and provide inputs for future funding considerations. Utilizing strategic asset management solutions, facilities leaders should be able to answer the following questions and objectively advocate for the proper inclusion of facility condition information in master planning efforts:

- What assets are currently installed in the facility?

- How are those assets performing based on age and condition?

- What is the appropriate operational investment to recover or maintain optimal performance?

- What function or space does an asset serve?

- What is the business or clinical impact if that asset or system were to fail?

- How much would it cost to renovate or replace that asset proactively versus reactively?

- What are the current levels of deferred maintenance, and what level of investment is required to sustain or improve deferred maintenance levels and mitigate risks for the hospital or system?

- With data in hand, will non-facilities leadership consider a multiyear budgeting and forecasting approach to construct a strategic infrastructure investment plan for the facility that can be executed in parallel with other master planning directives?

Common and critical

Master planning is a common and critical function that will guide health care organizations for decades to come. Conversely, aging infrastructure in the U.S. health care field is a concern, and the current levels of deferred maintenance are the result of decades of underinvestment.

Therefore, health care facilities leaders are encouraged to define, track and objectively communicate facility condition information and increase collaboration with non-facilities leadership.

This will allow health care organizations to create a more comprehensive master plan that addresses both current needs and future challenges, ultimately improving patient care and operational efficiency.

Related article // Data to help health care facilities prioritize infrastructure investments

National benchmark data indicates that approximately 53% of major acute and non-acute health care infrastructure assets and/or systems have exceeded expected useful life and should be considered for replacement, according to the Brightly Origin National Infrastructure Benchmark Metrics tracked by Brightly Software, a Siemens company.

The relative consistency of deferred maintenance levels, as measured across the following major asset types, further suggests that many organizations could benefit from prioritized investment based on risk, criticality and impact to the overall environment of care:

- Life safety assets (approximately 49% deferred), including fire alarm and suppression, emergency power, automatic transfer switches and life safety branch power distribution.

- Medical gas (approximately 57% deferred), including compressors, vacuum pumps, oxygen tanks, alarm panels and zone valves.

- Heating, ventilating and air-conditioning assets (approximately 59% deferred), including air-handling units, boilers, chillers, cooling towers, and associated ductwork and distribution hardware.

- Electrical distribution (approximately 55% deferred), including critical and equipment branch primary distribution, transfer switches, transformers, interior and exterior lighting, and security systems.

- Plumbing (approximately 57% deferred), including water heaters, water softeners and purification systems, tanks, pumps, and associated domestic water and sewage distribution hardware.

- Architectural (approximately 55% deferred), including facades, roofing, glazing and interior finishes.

Health care facilities leaders should maintain a clear line of sight to engineering capacities and age- or condition-based deferred maintenance levels of all asset types. Regular communication of this information with non-facility leadership will enable more comprehensive master planning strategies.

About this data: Average deferred maintenance statistics are based on Dynamic Facility Condition Assessment (FCA) data collected and tracked since 2016. Averages are based on more than 140,000 assets and 110 million square feet of acute and non-acute health care occupancy types. All cited data was accurate as of Dec. 20, 2024. Benchmark metrics are provided for comparative purposes only and should not be used in place of actual FCA data as individual hospital or health system data may vary significantly from the national averages.

Mark Mochel, CHFM, PMP, ACABE, is a strategic account executive at Brightly, a Siemens company. He can be reached at mark.mochel@brightlysoftware.com.