Kaleidoscopic strategies for therapeutic facilities

The 386,000-square-foot Nationwide Children’s Hospital Big Lots Behavioral Health Pavilion in Columbus, Ohio, makes generous use of open-air porches, courtyards and play decks as secondary treatment spaces.

Design by architecture+ and NBBJ; and image by Edward Caruso Photography

Facility planners, architects, designers, clinicians, contractors and solutions providers have the opportunity with each project decision they make to focus a kaleidoscope of considerations, constraints and conditions to create behavioral and mental health treatment spaces that are safe, effective and dignified, and defy stigma by design.

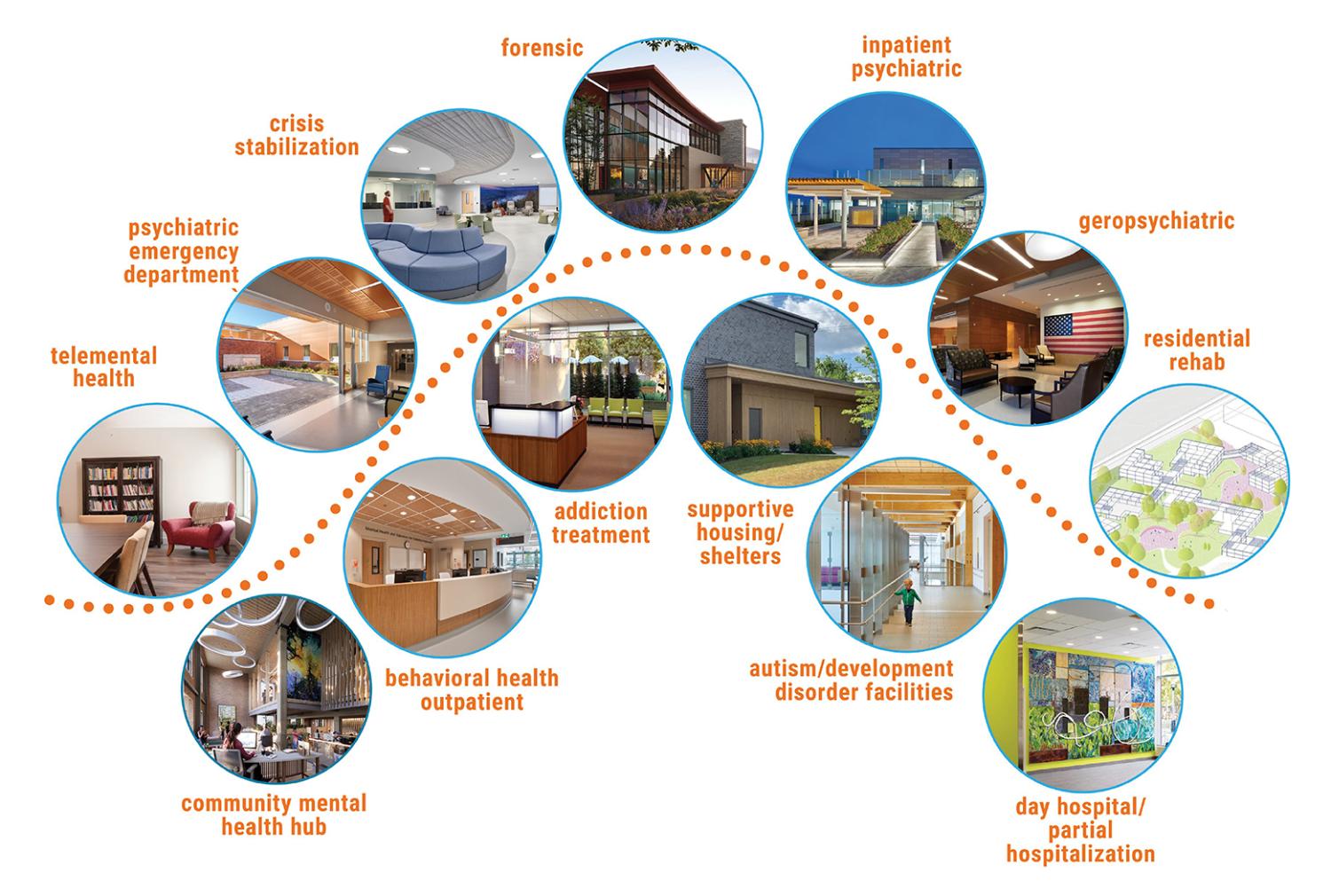

The exponential growth in demand for a wide range of new and renovated facility types — from inpatient psychiatric settings to crisis centers and integrated behavioral and mental health clinics serving a wide range of clinical needs — creates great responsibility for shaping the role and impact the physical environment has on behavioral and mental health care, treatment, safety and experience for generations of patients, families and caregivers to come.

The Center for Health Design’s Behavioral and Mental Health Environment Network, composed of seasoned executives and practitioners from the behavioral and mental health provider, architecture and design, and solutions/manufacturing sectors, surveyed its members regarding the top issues and design considerations they encounter when working on behavioral and mental health environments spanning the continuum of care worldwide.

The authors of the survey collaborated closely to provide overlapping examples of shared themes for behavioral and mental health design — safety, agency and autonomy, and defying stigma — explaining synergies and actionable strategies and providing examples of patient-centered approaches for those involved in planning, designing and building these environments.

Design is an active process, and continuous investigation, innovation and improvement provide greater agency to address behavioral and mental health disorders in all forms and for the benefit of all affected families, friends and communities.

This kaleidoscope of design strategies, research studies and best practices provides overlapping lenses to focus, reflect and enhance designers’ impact on behavioral and mental health environments.

Theme 1: Physical and perceived safety

One of the foremost considerations in designing recovery-focused behavioral and mental health environments is patient and staff safety, which includes both actual safety and perceived safety.

Research by Ann S. Devlin, Jack L. Nasar, Roger S. Ulrich and others shows that therapy outcomes are enhanced in calming, trauma-informed environments, and the design of the environment contributes significantly toward its success. Research by Erving Goffman, Carl R. Rogers and others further indicates that therapeutic results improve in environments that also are normalizing and non-institutional.

Virginia’s Central State Hospital features clear staff sightlines to subdivided bedroom wings and views into all daytime patient spaces within a cone-of-vision under 180 degrees.

Image courtesy of Page

Today’s leading behavioral and mental health facility designs go beyond balancing security with aesthetics, truly integrating these elements into a cohesive, normalizing design. The following are examples of how a building’s design can support both the goals of therapy and safety:

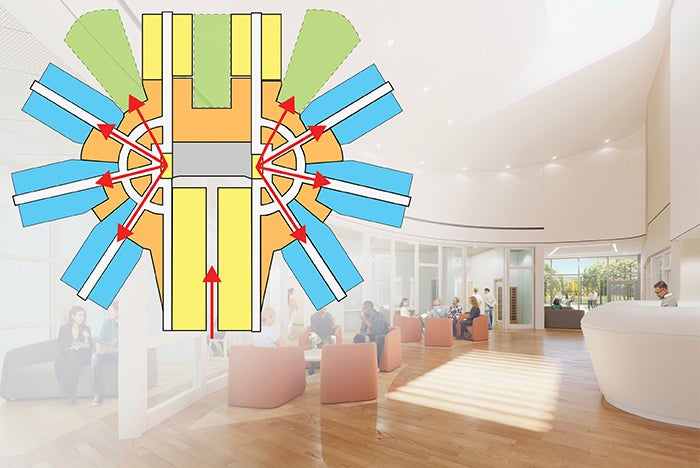

Floor plan and spatial design. The physical layout of spaces plays a critical role in ensuring safety. Designers should prioritize designs featuring staff sightlines to all patient areas, comfortable spatial and social density, clear and unobstructed circulation, and spaces for de-escalation and respite. Hard-to-observe spaces, such as niches, remote corners and patient stairs, should be limited.

Matt Connolly, president of Mindspring Mental Health Alliance in Des Moines, Iowa, recalls, “I found it comforting to have an open floor plan where I could see the staff while I was recovering in a psychiatric hospital.”

In inpatient settings, subdividing units into manageably sized bedroom clusters with consideration for shorter corridor travel distances enhances safety by improving staff awareness and intelligibility. Separate offstage transportation of food, medications and linens, along with remote building system maintenance, can further enhance safety by reducing traffic through patient areas.

Pairing two living units with a common staff core is an effective design strategy to provide offstage circulation, space efficiency and quick staff backup when needed. Areas that have historically posed safety concerns, such as vertical circulation and toilet rooms, should be carefully evaluated with clinical and security teams during the design process.

Safe, durable fixtures and products in compliance with federal, state and appropriate accrediting bodies. Integrating safe, durable and normalizing fixtures and products is an important element of safety. Recent developments feature many new attractive, safety-enhancing products, such as doors, windows, plumbing and light fixtures, hardware, finishes, furnishings and electronic security systems.

These products give architects and facilities teams a wide range of choices to evaluate for ligature risk, weaponization, ingestion, durability and contraband concealment that support a normalized, uplifting environment.

Staff respite. Safety and the perception of safety for staff is equally important in promoting a safe environment. Adequate staff respite spaces with natural light and outdoor access help staff decompress and prevent arousal fatigue. Additionally, thoughtfully designed building elements, such as monolithic open-protective staff stations, further provide staff safety while maintaining openness with patients, which has been shown to be beneficial, according to the article “Psychiatric ward design can reduce aggressive behavior” by Ulrich, et al., in the June 2018 issue of the Journal of Environmental Psychology.

Daylight and colors. Thoughtful color selections, ample natural light in the design and circadian lighting systems can improve sleep and reduce stress, contributing to the overall safety of the environment.

Outdoor safety. Patient wellness is enhanced by time outdoors, and exterior spaces can be designed to be restorative yet safe retreat and activity areas. Courtyards enclosed with building facades can feel less correctional than fencing, and exterior detailing can minimize ledges and joints, reducing opportunities for climbing or elopement.

Plantings, artificial turf, sports pavement areas, furnishings and walking trails should be properly selected and positioned to support patient respite without sacrificing safety.

Theme 2: Agency and autonomy

Agency is the cornerstone of human motivation, resilience and mental well-being. When individuals feel in control of their lives, they’re more likely to pursue their goals with vigor and maintain a positive outlook, according to the website neurolaunch.com.

The physical environment can significantly impact individuals’ experience and perception of care. In times of helplessness and hopelessness, even the smallest elements in the physical environment can support one’s sense of agency — something that they may feel deprived of as they enter treatment.

Courtyards enclosed by building facades at the Royal Columbian Mental Health & Substance Use Wellness Centre in British Columbia, Canada, welcome visitors with a less institutional feel than fencing, while detailing for courtyards minimizes climbing opportunities to reduce elopement risks.

Image courtesy of Stantec Architecture and architecture+

Designer, former patient and lived experience advocate Shahad Sadeq reflects on the impact of design on patients’ mindsets, stating, “Beauty confers dignity. Space itself is not the source of human dignity, but it shapes our awareness of our own humanity. When spaces lack autonomy, choice, privacy, tactile comfort and, most of all, beauty, they send a message — one that becomes painfully apparent in times of crisis: You are not valued. You are not seen. You are not worthy of care.”

Opportunities for agency through design should exist throughout the following stages of a journey to recovery:

Arrival and intake. Arrival experiences are among the most stressful points in a patient’s journey. At the CHS Dauphin Crisis Center in Harrisburg, Pa., the environment communicates a sense of welcome and transparency to reduce fear, aid a warm hand-off and alleviate the uncertainty associated with seeking treatment.

Designers can help individuals feel more empowered and support navigation through difficult transitions by increasing glazing at building entries and secure vestibules, as well as maximizing visibility within waiting and intake areas. Any person in a new environment needs to know, “What is going to happen to me next?”

Milieu and socialization space. Patients along the continuum of care spend much of their time in social milieu and group environments. Spacious corridors and multipurpose areas afford increased personal space associated with reduced stress and anxiety due to crowding, according to the 2012 paper “Towards a design theory for reducing aggression in psychiatric facilities” by Ulrich, et al., and published for the ARCH12 Conference in Sweden.

Connolly notes, “Not everyone has the same illness, so it is important to be able to choose to engage with other patients or to sit by yourself.”

Serving all individuals ages 14-plus experiencing behavioral health and substance use crises, the CHS Dauphin County Crisis Walk-In Center in Harrisburg, Pa., offers spacious multipurpose areas that maximize visibility while accommodating increased personal space associated with reduced stress.

Image courtesy of Stantec Architecture

Incorporation of such trauma-informed design concepts is fundamental to balancing the ever-changing sensory and social needs that individuals experience on their journey to recovery. Designers should provide a range of settings to accommodate privacy as well as socialization.

Agency and normalcy are further enhanced by time outdoors, especially where options for both private retreat and gross motor movement are present. Such environments have been shown to incentivize positive behaviors and increase treatment efficacy.

In a 2021 post-occupancy evaluation of Nationwide Children’s Hospital Behavioral Health Pavilion in Columbus, Ohio, staff identified areas such as open-air porches, courtyards and play decks as secondary treatment spaces that support self-regulating behaviors. Staff noted that when youth become dysregulated, they are given the choice to take a break in an alternative environment, thereby mitigating interruptions to therapy.

Other techniques to offer individuals a sense of agency in treatment environments across the continuum of care include:

- Single occupancy environmental controls. This includes full spectrum light fixtures, integrated operable window treatments, sound/music selection and safe operable windows, such as in long-term and residential facilities.

- Dignity design. Design elements should work to strike a balance between compliance with federal, state and appropriate accreditation bodies’ regulatory requirements and the right to an individual’s need for privacy.

- A means for creative expression. Design should work with the clinical staff to create safe opportunities for individual and collective creativity. While the quality of care will always matter most, empowering patients and residents with choices in their environment can relieve anxiety, improve engagement and build a sense of hope for recovery.

Theme 3: Defying stigma

Throughout history, society has been confronted through various media with the inhumane, institutional and impersonal image of behavioral and mental health disorders and treatment. Even today, people often make negative assumptions about those living with behavioral and mental illness and the places in which they receive treatment.

These common misconceptions in film and other media continue to reinforce stigma and a sense of shame among those who are suffering.

The location, siting and architecture of a facility can do tremendous work in reducing stigma. Through integration into the urban fabric or established campus architecture, a behavioral and mental health facility can present to the community as a positive health care facility that is simply another component of a health care system.

The 38-bed Healing Spirit House, located on the 244-acre Riverview Lands in Coquitlam, British Columbia, uses naturally daylit spaces with familiar materials and inviting colors that evoke optimism and vitality.

Design by HDR and image © 2019 Ed White

Alternatively, when the appropriate setting is suburban or rural, the approach and surrounding landscaping can establish a welcoming message of a beautiful setting for high-quality care.

In either case, through careful site selection and site planning, the experience of approaching a building type that has historically been shrouded in fear and shame can be replaced by one of hope and dignity.

Architecture has the power to make a positive impression. Institutional buildings often are honest about what occurs within; imposing massing reinforces the stereotype of what individuals have been taught to expect in a psychiatric facility.

In contrast, a building composed of familiar materials, with calming fenestration patterns and security systems that are virtually invisible can diminish the fear of the unknown for patients who may be arriving for the first time or their loved ones coming for a visit.

By designing in a way that introduces a human scale to the building, thus making it easier to understand and ultimately navigate, designers can create places that defy the expectations of stigma upon arrival.

Thoughtful planning can defy stigma by design and combat the misperceptions of mental illness. Traditional stereotypes, such as long monotonous corridors, unflattering fluorescent lighting and an abundance of cold, metal surfaces, all contribute to stigma.

Conversely, naturally daylit spaces with familiar materials and unobtrusive safety features can break the institutional stereotype and be applied at various scales throughout the facility to establish a sense of welcome and comfort.

Cooper University Health in Camden, N.J., employs sensory-enabled architecture incorporating tactile, auditory, olfactory, visual and kinetic elements in design.

Image courtesy of Stantec

While safety is of utmost importance, breaking down barriers between patients and staff with safety as an underlay introduces a more progressive and dignified environment. Positive care culture can be crafted by listening to all voices and considering diverse perspectives through the involvement of a broad range of participants, including patients and families with lived experience, throughout the design process.

Behaviors and perceptions of those experiencing mental illness can be challenging to comprehend. However, with patience and empathy, listening to those with lived experience can reveal unexpected design solutions and grant people suffering mental illness the opportunity to retain a powerful sense of self and demonstrate their value to others.

Planning a brighter future

Health care facilities designers have the responsibility to learn deeply and craft care cultures that foster safety, resilience, empowerment and healing. “We need to be asking how we can design spaces that foster dignity,” Sadeq shared in reflection of her experience.

From strategically planning facility layouts to details that ensure a safe and dignified patient experience, designers can advocate with each line drawn and brick laid. By focusing these overlapping lenses of safety, agency and destigmatization, designers can plan a brighter future together.

Related article // The Behavioral and Mental Health Environment Network

The Behavioral and Mental Health Environment Network is one of The Center for Health Design’s collaborative networks for executive-level leaders involved in the planning, design and operations of environments that support best practices, safety and recovery for individuals suffering from behavioral and mental health issues.

The Center provides the network with dedicated programming and facilitated learning opportunities to members who drive conversations and topics of interest. Networking and communication, both in person and through an online forum, provide members with year-round access to learning, innovating, problem-solving and relationship-making experiences.

At last year’s annual in-person network meeting, members gathered for two days in Columbus, Ohio, touring several area facilities, including the partial hospitalization program/Ronald McDonald Room and psychiatric crisis department at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, the 72,000-square-foot Franklin County Mental Health and Addiction Crisis Center, and Twin Valley Behavioral Healthcare.

As part of the network’s broader mission to share and drive positive change across the field, a panel of members presented “Behavioral and Mental Health Design: Top Challenges and Future Opportunities” at the 2025 International Summit & Exhibition on Health Facility Planning, Design & Construction™ in Atlanta.

Panelists provided a collective glimpse into the top challenges and future opportunities for behavioral and mental health organizations that the network members have been addressing over the past year. They shared insights gleaned from their collaborative, deep-dive, innovation sessions, site visits and collective experiences. They described the critical issues facing today’s behavioral and mental health providers and the innovative solutions they are seeing nationally and internationally.

By sharing this often hard-earned knowledge, members reflect their hope to design a brighter future for humanity at its most vulnerable and be a call to action for the most marginalized in their communities.

To learn more, contact The Center at info@healthdesign.org.

About this article

This is one of a series of articles published by Health Facilities Management in collaboration with The Center for Health Design. The authors are members of The Center’s Behavioral and Mental Health Environment Network.

Stephen Parker, AIA, NOMA, NCARB, LEED AP, is mental and behavioral health planner at Stantec Architecture, and Brian Giebink, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, EDAC, is behavioral and mental health practice leader at HDR. They can be reached at stephen.parker2@stantec.com and brian.giebink@hdrinc.commailto:stephen.parker2@stantec.com. They were assisted by co-authors Melanie Baumhover at BWBR, Eric Kern at Page, Gina Livingston-Smith at NBBJ and Sara Wengert at architecture+.